Research Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2025) Volume 14, Issue 11

Electrochemical Technologies for Drug and Alcohol Detection

Luke Saunders*Luke Saunders, Department of Electrical Engineering, School of Engineering, Merz Court, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 8QB, UK, Email: luke.saunders@ncl.ac.uk

Received: 16-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-169942; Editor assigned: 18-Aug-2025, Pre QC No. JDAR-25-169942 (PQ); Reviewed: 01-Sep-2025, QC No. JDAR-25-169942; Revised: 10-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-169942 (R); Published: 17-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236483

Abstract

Drugs and alcohol have dual roles in society, offering therapeutic value yet causing harm. Detection methods span environmental and biomedical fields, employing electrochemical sensors and aptamer-based technologies. These systems provide sensitive, selective monitoring of analytes, advancing public health efforts through real-time assessment of substance presence in diverse settings.

Keywords

Drug; Electrochemical technologies; Central nervous system

Introduction

The use of plant derived medicines has been around for centuries [1,2], and ever since then, humanity has had a long and complicated history with drugs and alcohol. On the one hand, there are drugs which are extremely beneficial to humanity such as polyenes for anti-fungal treatments [3,4] and plant derived phenolic compounds as antioxidants [5,6], but there are also some which cause great harm to people and wider society such as opioids [7,8]. But to complicate matters further, there are drugs to counteract the drugs (such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naloxone), which can be used to treat opioid overdose or opioid intoxication [9-12]. Thus, it would seem society has categorised drugs as either “good” or “bad” depending on their physiological effects on humans. The "illicit" drugs are typically used recreationally and can damage the Central Nervous System (CNS) which often leads to various health problems [13,14]. However, society’s values can change over time. This is evidenced by the fact that in 1898 “heroin” was a constituent of some cough medicines [15,16].

The same level of apparent ambiguity and selectivity of social acceptability is also true of alcohols. For example, there is “rubbing alcohol” (concentrated propan-2-ol) which is widely available and used as a disinfectant in many clinical settings and households within the UK; but there is also ethanol in most alcoholic beverages, which is one of the main causes of intoxication within people and animals and the subsequent “hangovers” that people experience. Although, it must be mentioned that in many parts of the world (and in many religions), anything containing alcohol is banned entirely (whether propan-2-ol, ethanol or any other hydrocarbon containing the alcohol chemical functional group).

Drug and alcohol detection can be broadly broken down into two categories, in vivo detection within organisms (humans, bacteria etc.) and detection within the environment. Here, we will consider the technologies commonly used for either scenario and briefly discuss their princpile working mechanisms and the scientific theories that underpin them.

Drug and alcohol detection in the environment

The detection of drugs and alcohol within the environment often involves having to take samples from numerous different sample sites to get enough reliable data to form an accurate idea of the analyte distribution within the target area and any long-term or short-term trends for the presence of analytes of interest. There are many different methods of detection to choose from, depending upon factors such as speed, accuracy, and portability. Examples include portable ethanol sensors for breath analysis by the police [17-20], and electrochemical detection of cocaine within wastewater [21,22]. There are also electrochemical methods of detecting various alcohol vapours [23,24]. Such electrochemical sensors have been widely studied for years [25,26], and are so ubiquitous that they merit further explanation within this manuscript.

Drug and alcohol detection in the body

The detection of drugs and alcohol within people has been an area of active research for decades, although Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TPM) is generally considered unnecessary for many commonly used medications [27]. Examples include therapeutic drug monitoring via concentration levels in the blood [28-31] and drug monitoring in urine [32,33]. Electrochemical aptamer based (EAB) sensors have been used for decades to detect a wide range of biological targets [34-37], and are a promising area of research for in situ monitoring within the body [38,39].

Principles of electrochemical sensing

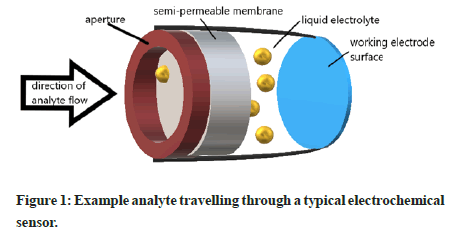

All electrochemical sensors work on the fundamental principle of electrochemical reactions at the Working Electrode (WE) surface to cause the transfer of electrons into or out of the working electrode, which is then registered as a current flowing through the electrical circuit system. This current can provide quantitative data as it is typically proportional to the amount of analyte reacting at the working electrode surface [40,41]. The reactions at the working electrode can be broadly classed as either chemisorption, oxidation, or reduction. In most standard sensor designs, the analyte must physically move from the inlet (or aperture) at one end of the sensor, to the other end where the WE surface is located. This means passing through several different mediums such as a semi-permeable membrane, a liquid electrolyte, and finally interesting with the working electrode surface (Figure 1). Whilst the analyte interaction with the WE surface is typically the focus during electrochemical sensing, other aspects such as the diffusion rate of the analyte through the different mediums, and the physical length of the different sensor layers can be used to give useful analytical data [42,43].

Figure 1: Example analyte travelling through a typical electrochemical sensor.

Electrochemical Aptamer Based Sensors (EABs)

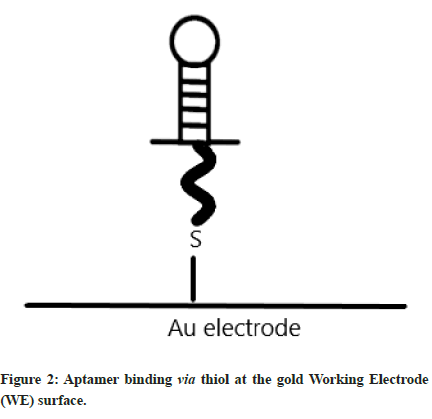

Having already discussed the working mechanisms of electrochemical sensors in general, now we turn our attention specifically to EABs. Aptamers are short, single stranded nucleic acid sequences which are typically derived from either DNA or RNA. They can exhibit high selectivity for binding to the target analyte and can be chemically modified to improve their performance [44,45]. Selection of aptamers is often via an in vitro procedure called SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment) [46-49], which can search through a library of hundreds of different possible options. There are lots of different available aptamers which have been studied in the literature, designed to detect things such as cancer, macular degeneration, and carotid artery disease [50-53]. One of the most common target analytes for EABs is thrombin [54-57] (which is an enzyme involved in the blood clotting cascade by converting fibrinogen in to fibrin). Aptamers are typically immobilised via thiol functional groups linked to the gold (Au) electrode surface which acts as the WE [58,59]. An example of the thiol binding at the gold Working Electrode (WE) surface is shown for clarity (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Aptamer binding via thiol at the gold Working Electrode (WE) surface.

Conclusion

The principle working methods for electrochemical detection have been briefly discussed, and their usr for detection of drugs and alcohol both in the environment and within the body has been shown to be an active area of research. The electrochemical sensor technology for analyte detection is generally well understood and has been covered in depth within the literature previously.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges the help and support of Newcastle University. This work financially supported by the EPSRC UKRI (grant EP/S018034/1).

Data Access Statement

No new data were created during this study.

References

- A. Vickers, C. Zollman. Herbal medicine. BMJ. 1999;319:1050.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Kumar, D. Jabin. Drug discovery analysis for identification of therapeutic agents against aspergillus fumigates. J Drug Alc Res. 2023;12:236217.

- J.R. Wingard, P. Kubilis, L. Lee, G. Yee, E. Levine, et al. Clinical significance of nosocomial infections in bone marrow transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1402-1407.

- A. Lemke, A.F. Kiderlen, H. Kayser, et al. Amphotericin B. Appl. Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:151-162.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R. Niazmand, B. Razavizadeh. Ferula asafoetida: chemical composition, thermal behavior, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leaf and gum hydroalcoholic extracts. J Food Sci Technol. 2021;58:2148-2159.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Satorov, M. Buriyev, A. Khudaykulov. Total Polyphenol Content, Antioxidant Potential, Antibacterial and Antifungal Properties of Ferula L. Species Growing in Tajikistan. J Drug Alc Res. 2024;13(12):236424.

- B.F. Grant, R.B. Goldstein, T.D. Saha, S.P. Chou, J. Jung, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Jamal, R. Agaku, B.A. O’Connor. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2005-2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1108-1112.

- A.K. Clark, C.M. Wilder, E.L. Winstanley. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8:153-163.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Farrell, J. Ward, R. Mattick, W. Hall, J. Stimson, et al. Methadone maintenance treatment in opiate dependence: a review. BMJ. 1994;309:997.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Connock, A. Juarez-Garcia, S. Jowett, E. Frew, Z. Liu, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. NIHR J Libr. 2007;11:1-171.

- S.-C. Wang, L.-L. Hung, W.-H. Kuo, J.-S. Chiu, C.-F. Hsieh, et al. Opioid addiction, genetic susceptibility, and medical treatments: A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4294.

- E. Jane-Llopis, I. Matytsina. Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: a review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25(6):515-536.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. van Amsterdam, A. Opperhuizen, R. Koeter. Ranking the Harm of Alcohol, Tobacco and Illicit Drugs for the Individual and the Population. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16(4):202-207.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. Peppin, K. Dineen, A. Ruggles, J. Coleman. Prescription Drug Diversion and Pain: History, Policy, and Treatment. Oxford University Press; 2018.

- M. Chaudhary, A. Kumar, S. Shukla. Prospects of nanostructure-based electrochemical sensors for drug detection: A review. Mater Adv. 2023;4:432-457.

- J. Gadomska, M. Donten, W. Ciesielski, L. Nyholm. Mass transport-controlled steady-state currents for methanol in a flow injection system. Analyst. 1996;121:1869.

- M. Besson, P. Gallezot, J. Fuertes, et al. Selective oxidation of alcohols and aldehydes on metal catalysts. Today. 2000;57:127.

- A.V. Tripkovic, S.L.-J. Gojkovic, N.M. Dimitrov, et al. Methanol oxidation at platinum electrodes in acid solution: comparison between model and real catalysts. J Serb Chem Soc. 2006;71:1333.

- S.N. Raicheva, G.A. Angelov, V. Lazarov. Mechanism of the electrooxidation of ethyl alcohol and acetaldehyde on a smooth platinum electrode: II. The effect of acetaldehyde on the processes of formation and removal of the surface oxide. Electroanal Chem Inter Electrochem. 1974;55:213.

- Z. Yang, E. Castrignano, D. Bagnati, et al. Community sewage sensors towards evaluation of drug use trends: detection of cocaine in wastewater with DNA-directed immobilization aptamer sensors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21024.

- A. Florea, M. Jong, K. De Wael. Electrochemical strategies for the detection of forensic drugs. Curr Opin Electrochem. 2018;11:34-40.

- C.K. Chung, C.A. Ku. An effective resistive-type alcohol vapor sensor using one-step facile nanoporous anodic alumina. Micromachines. 2023;14(7):1330.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.M. Laera, M. Penza, R. Rossi. Chemiresistive materials for alcohol vapor sensing at room temperature. Chemosensors. 2024;12(5):78.

- H. Okamoto, H. Obayashi, T. Kudo. Carbon monoxide gas sensor made of stabilized zirconia. Solid State Ionics. 1980;1:319-326.

- J. Stetter, J. Li. Amperometric gas sensors a review. Chem Rev. 2008;108:352-366.

- J.S. Kang, M.-H. Lee. Overview of therapeutic drug monitoring. Korean J Intern. Med. 2009;24(1):1-10.

- G. Hempel. Dose and therapy individualisation in cancer chemotherapy. Handbook of Analytical Separations. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004.

- F. Saint-Marcoux, E. Sauvageon-Martre, G. Lachâtre. Current role of LC-MS in therapeutic drug monitoring. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;388:1327-1349.

- M.J. Bogusz. Editor's preface. Handbook of Analytical Separation. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000.

- H. Kataoka. Recent developments and applications of microextraction techniques in drug analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;396:339-364.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- X. Liu, Z. Yu, W. Yu, H. Wu, J. Zhang. Therapeutic drug monitoring of polymyxin B by LC–MS/MS in plasma and urine. Bioanalysis. 2020;12(12):845-855.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.A. Huestis, E.J. Cone, C.J. Wong. Monitoring opiate use in substance abuse treatment patients with sweat and urine drug testing. J Anal Toxicol. 2000;24(7):509-521.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B.S. Ferguson, D.A. Hoggarth, D.P. Maliniak. Real-time, aptamer-based tracking of circulating therapeutic agents in living animals. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:213ra165.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Xiao, A.A. Lubin, Y. Heeger, K.W. Plaxco. Single-step electronic detection of femtomolar DNA by target-induced strand displacement in an electrode-bound duplex. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:16677-16680.

- Y. Xiao, A.A. Lubin, A.J. Heeger, K.W. Plaxco. Label-Free Electronic Detection of Thrombin in Blood Serum by Using an Aptamer-Based Sensor. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:5592-5595.

- J. Liu, H. Zhou, J.-J. Xu, H.-Y. Chen. An effective DNA-based electrochemical switch for reagentless detection of living cells. 2011;47:4388-4390.

- N. Arroyo-Currás, J. Somerson, K.W. Plaxco. Real-time measurement of small molecules directly in awake, ambulatory animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:645-650.

- X. Ji, X. Lin, J. Rivnay. Organic electrochemical transistors as on-site signal amplifiers for electrochemical aptamer-based sensing. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:1665.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Hossain, J. Saffell, R. Baron. Differentiating NO2 and O3 at Low Cost Air Quality Amperometric Gas Sensors. ACS Sens. 2016;1(11):1291-1294.

- R. Baron, J. Saffell. Amperometric Gas Sensors as a Low Cost Emerging Technology Platform for Air Quality Monitoring Applications: A Review. ACS Sens. 2017;2(11):1553-1566.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. Saunders, L.K. Mudashiru, J.R. Baron. Diffusion Models of Mass Transport for the Characterisation of Amperometric Gas Sensors. 2024;11(5):202300708.

- L. Saunders, R. Baron, B.R. Horrocks. Amperometric Alcohol Vapour Detection and Mass Transport Diffusion Modelling in a Platinum-Based Sensor. 2025;6(3):24.

- C.S. Ferreira, S. Missailidis. Aptamer-based therapeutics and their potential in radiopharmaceutical design. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2007;50:63-76.

- S.D. Jayasena. Aptamers: An Emerging Class of Molecules That Rival Antibodies in Diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 1999;45:1628-1650.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Xu, G. Cheng, P. He, Y. Fang. A Review: Electrochemical Aptasensors with Various Detection Strategies. Electroanalysis. 2009;21(11):1219-1333.

[Crossref]

- A. Sassolas, B. Leca-Bouvier, L.J. Blum. Electrochemical Aptasensors. Electroanalysis. 2009;21(11):1237-1250.

- M.A. Syed, S. Pervaiz. Advances in Aptamers. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:215-224.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.-E. Radi, M.R. Abd-Ellatief. Electrochemical Aptasensors: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Diagnostics. 2021;11(1):104.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E.S. Gragoudas, A.P. Adamis, E.T. Cunningham, D.R. Feinsod, J. Guyer, et al. Pegaptanib for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2805-2816.

- P.J. Bates, D.A. Laber, D.M. Miller. Discovery and development of the G-rich oligonucleotide AS1411 as a novel treatment for cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009;86:151-164.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Shangguan, Z. Cao, L. Meng. Cell-Specific Aptamer Probes for Membrane Protein Elucidation in Cancer Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:2133-2139.

- S. Tope, S. Maske, R. Puranik. Ameliorative potential of rutin on streptozotocin-induced neuropathic pain in rat. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Res. 2013;3:2718-2743.

- P. Kara, J. Tamer, N. Akkaya. Aptamers based electrochemical biosensor for protein detection using carbon nanotubes platforms. 2010;26:1715-1718.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Lu, N. Zhu, P. Yu, L. Mao. Aptamer-based electrochemical sensors that are not based on the target binding-induced conformational change of aptamers. Analyst. 2008;133:1256-1260.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Z. Yan, Z. Han, H. Huang, H. Shen, X. Lu. Rational design of a thrombin electrochemical aptasensor by conjugating two DNA aptamers with G-quadruplex halves. Anal. Biochem. 2013;442:237-240.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. Zheng, L. Lin, G. Cheng, et al. Study on an electrochemical biosensor for thrombin recognition based on aptamers and nano particles. Sci. China Ser. B Chem. 2007;50:351-357.

- D.V. Leff, L. Brandt, J.R. Heath. Synthesis and Characterization of Hydrophobic, Organically-Soluble Gold Nanocrystals Functionalized with Primary Amines. Langmuir. 1996;12:4723-4730.

- F.V. Oberhaus, D. Frense, D. Beckmann. Immobilization Techniques for Aptamers on Gold Electrodes for the Electrochemical Detection of Proteins: A Review. Biosensors. 2020;10(5):45.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Copyright: © 2025 Saunders L. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.