Research Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2025) Volume 14, Issue 10

Update on Myasthenia Gravis and Novel Drug Therapy Approach

Joseph Sibi1, Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes2 and Humberto Foyaca3*2Department of Neurology, Walter Sisulu University (WSU), South Africa

3Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

Humberto Foyaca, Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa, Email: humbertofoyacasibat@gmail.com

Received: 11-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-170989; Editor assigned: 15-Sep-2025, Pre QC No. JDAR-25-170989 (PQ); Reviewed: 29-Sep-2025, QC No. JDAR-25-170989; Revised: 17-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-170989 (PQ); Published: 24-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236473

Abstract

Introduction: Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune, heterogeneous disease that affects neuromuscular transmission, with approximately 50% of patients with ocular MG progressing to generalized disease within two years. We present a comprehensive case study detailing the natural history of MG progression in a young woman over a four-year period.

Conclusions: Most of our revised cases illustrate the complete spectrum of MG presentation, emphasizing the importance of early recognition, appropriate risk stratification, and proactive management to prevent a crisis. The progression from ocular to generalised disease and ultimately to crisis highlights critical decision points in MG management.

Keywords

Myasthenia gravis; Myasthenic crisis; Acetylcholine receptor antibodies; Ocular myasthenia; Muscle-specific kinase; Thymectomy

Introduction

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is a relatively common neuromuscular junction disorder, with recent epidemiological data indicating an increasing global recognition and diagnosis [1-4]. Recent large-scale population studies have demonstrated considerable variations across studies, with prevalence ranges of 15-329 per million, and a diagnosed prevalence of 37.0 per 100,000 persons in the United States in 2021. This autoimmune condition is characterised by fluctuating Weakness affecting ocular, bulbar, limb, and respiratory muscles, resulting from antibody-mediated disruption of neuromuscular transmission [2,5,6].

These distinct antibody profiles aid diagnosis and influence clinical phenotype, treatment response, and prognosis, forming the basis for personalised therapeutic approaches [5,7,8].

The clinical spectrum of MG ranges from isolated ocular involvement to life-threatening myasthenic crisis [5,6,9]. Ocular Myasthenia Gravis (OMG), characterized by ptosis and diplopia without generalized weakness, represents the initial presentation in approximately 85% of cases. However, the risk of progression to generalised disease remains substantial, with studies demonstrating that 50- 60% of OMG patients develop systemic involvement within two years if left untreated [7].

This comprehensive review aims to illustrate key diagnostic challenges, therapeutic decision points, and practical management strategies that can guide clinicians in recognising and treating this autoimmune condition.

The differential diagnosis for isolated ocular symptoms included thyroid eye disease (excluded by normal thyroid function and absence of proptosis or lid retraction), oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (excluded by age and lack of family history), mitochondrial myopathy (excluded by normal lactate and absence of other systemic features) [8,10,11]. Given the diagnosis of ocular MG with positive AChR antibodies, treatment was initiated with pyridostigmine 30 mg three times daily, gradually titrated to 60 mg four times daily based on symptom response [5,12].

Materials and Methods

Treatment decision rationale

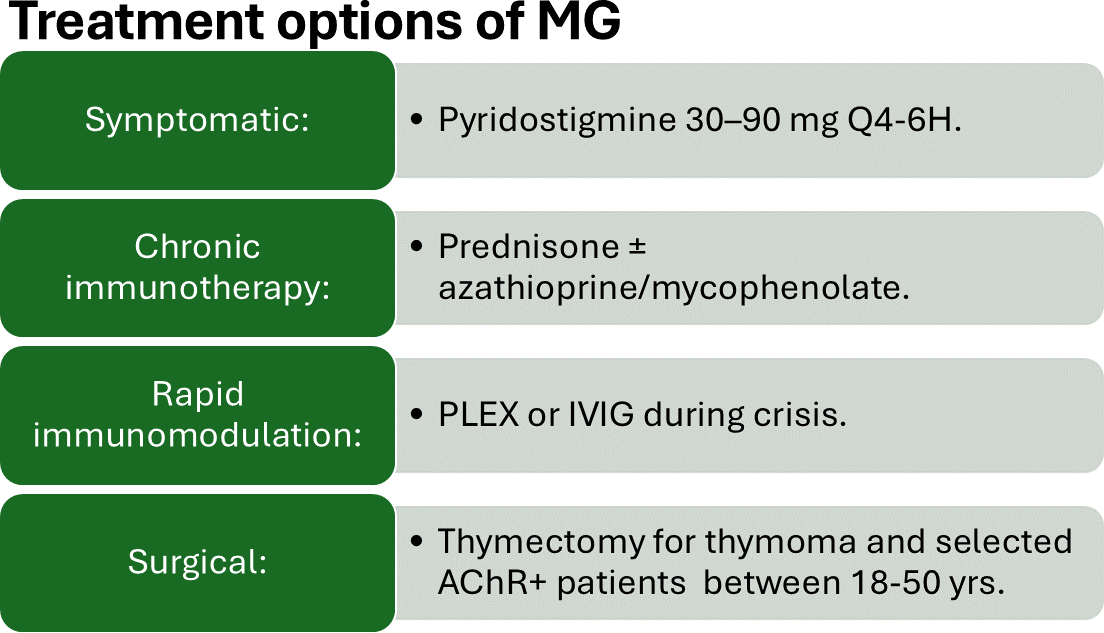

The most common modalities of treatment can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Shows different modalities of therapies

The decision to initiate immunosuppressive therapy is based on established risk factors for disease progression, including a young age (<40 years), positive AChR antibodies, thymic hyperplasia, and the development of generalized symptoms [12,13]. Contemporary evidence suggests that early immunosuppression in such patients may prevent further progression and reduce the risk of myasthenic crisis [12,14]. The choice of prednisone as the first-line immunosuppression was based on international consensus guidelines, with azathioprine added as a steroid-sparing agent to minimize long-term corticosteroid exposure [12,14].

The six-month delay to thymectomy was due to patient preference for completing her academic semester and the need for multidisciplinary evaluation. Current guidelines support thymectomy in patients aged 18-65 years with generalized MG and thymic abnormalities, regardless of antibody status [12,15].

Results and Discussion

The progression from isolated ocular symptoms to generalised Weakness and ultimately to life-threatening crisis over four years illustrates several critical aspects of MG management that warrant detailed discussion considering contemporary understanding and therapeutic advances.

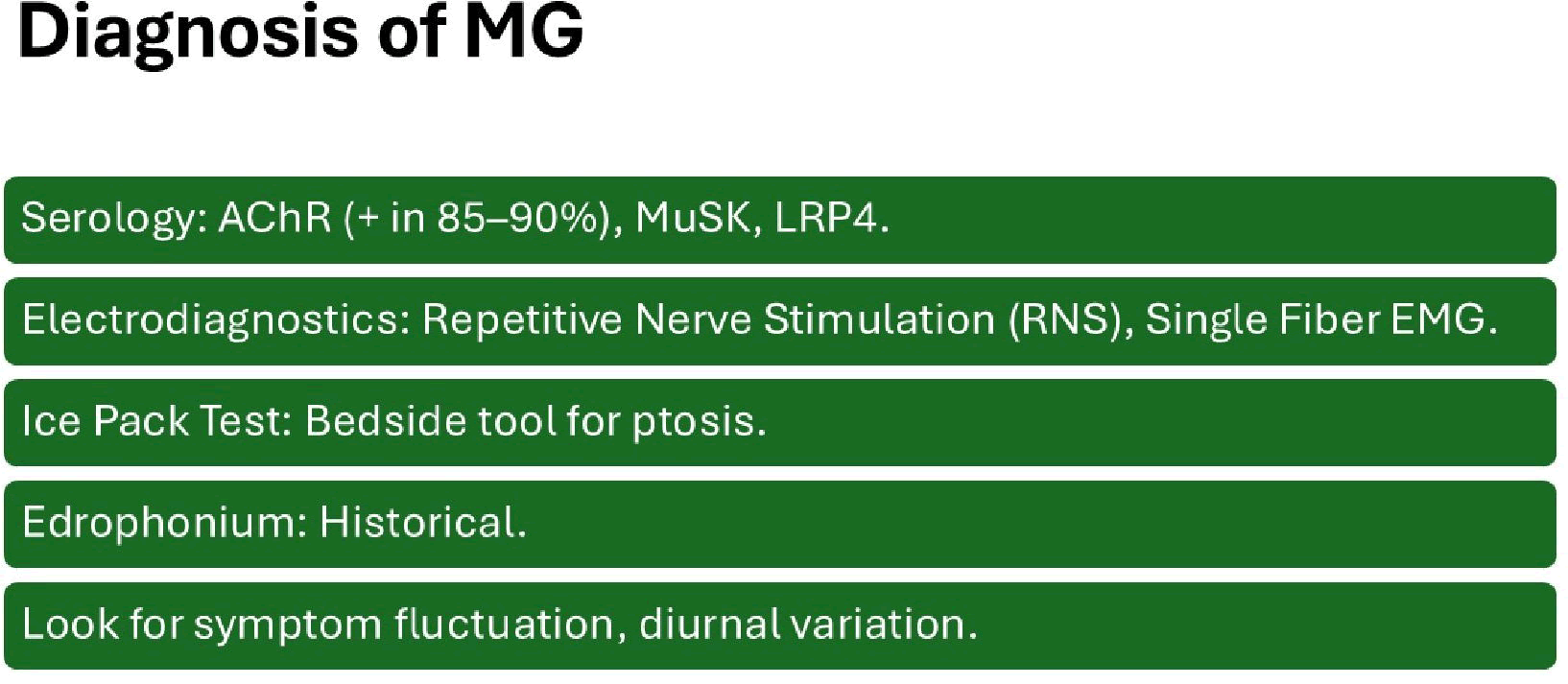

The most important elements to be considered for MG diagnosis are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Diagnosis

The clinical classification of MG can be seen in Table 1.

| Class I | Any ocular muscle weakness; may have weakness of eye closure. All other muscle strength is normal. Mild weakness affecting muscles other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity. |

| Class II | IIa) Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both. May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles. IIb) Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both. May also have limb, axial muscles, or both. |

| Class III | Moderate weakness affecting muscles other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity. IIIA) Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both. May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles. IIIb) Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both. May also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both. |

| Class IV | Severe weakness affecting muscles other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity. Iva) Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both. May also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles. IVb) Predominantly affecting oropharyngeal, respiratory muscles, or both. May also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both |

| Class V | Defined as intubation, with or without mechanical ventilation, except when employed during routine postoperative management (The use of a feeding tube without intubation places the patient in class IVb) |

Table 1: Clinical presentation of MG

Early recognition and the ocular phase

The predilection for ocular muscle involvement in MG reflects the distinct physiological properties of extraocular muscles, including smaller motor units, higher firing frequencies, and a reduced safety factor for neuromuscular transmission compared to limb muscles [10].

Contemporary validation studies support that the ice pack test’s diagnostic procedure has high utility, with sensitivity and specificity for MG when properly performed [11].

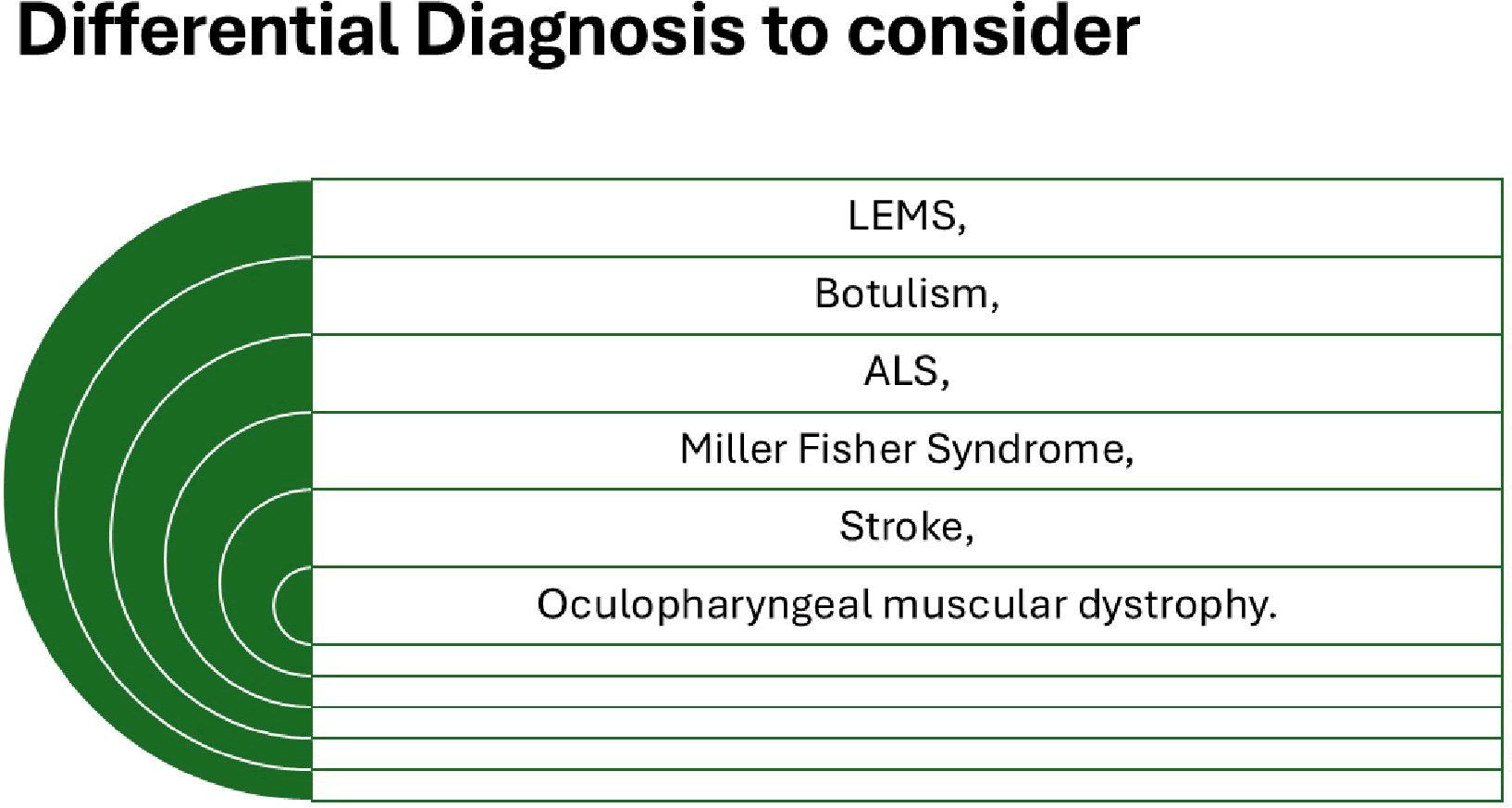

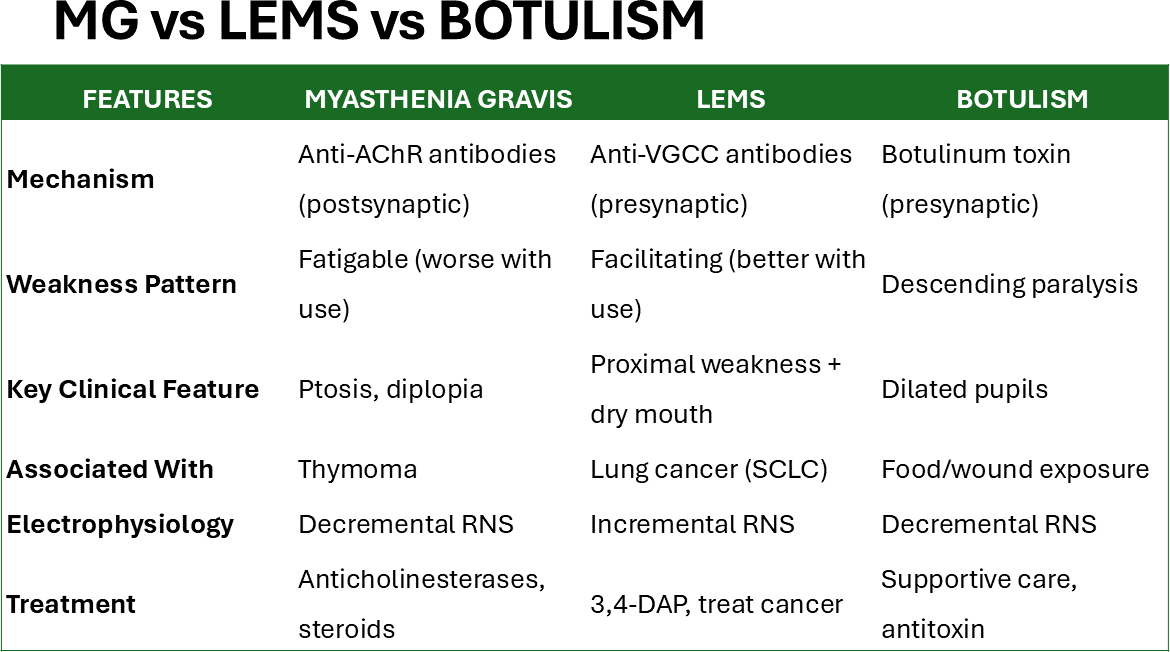

Some of the most common disorder to be differentiated with MG are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Differential diagnosis of MG

Progression to generalised disease: Risk stratification

The progression from ocular to generalised MG within two years aligns with established natural history data. Current research demonstrates that 50-60% of untreated OMG patients develop generalised Weakness within this timeframe. Contemporary risk stratification models have identified several predictors of generalisation, including positive AChR antibodies, abnormal repetitive nerve stimulation, and thymic abnormalities factors in our patient [12,13].

Recent therapeutic approaches suggest that early intervention with immunosuppression in high-risk ocular MG patients may prevent or delay progression to generalised disease, representing a paradigm shift from the traditional “wait and see” approach. The decision to initiate immunosuppressive therapy in our patient followed current evidence-based guidelines, with prednisone as the first-line immunosuppressive agent [12,14].

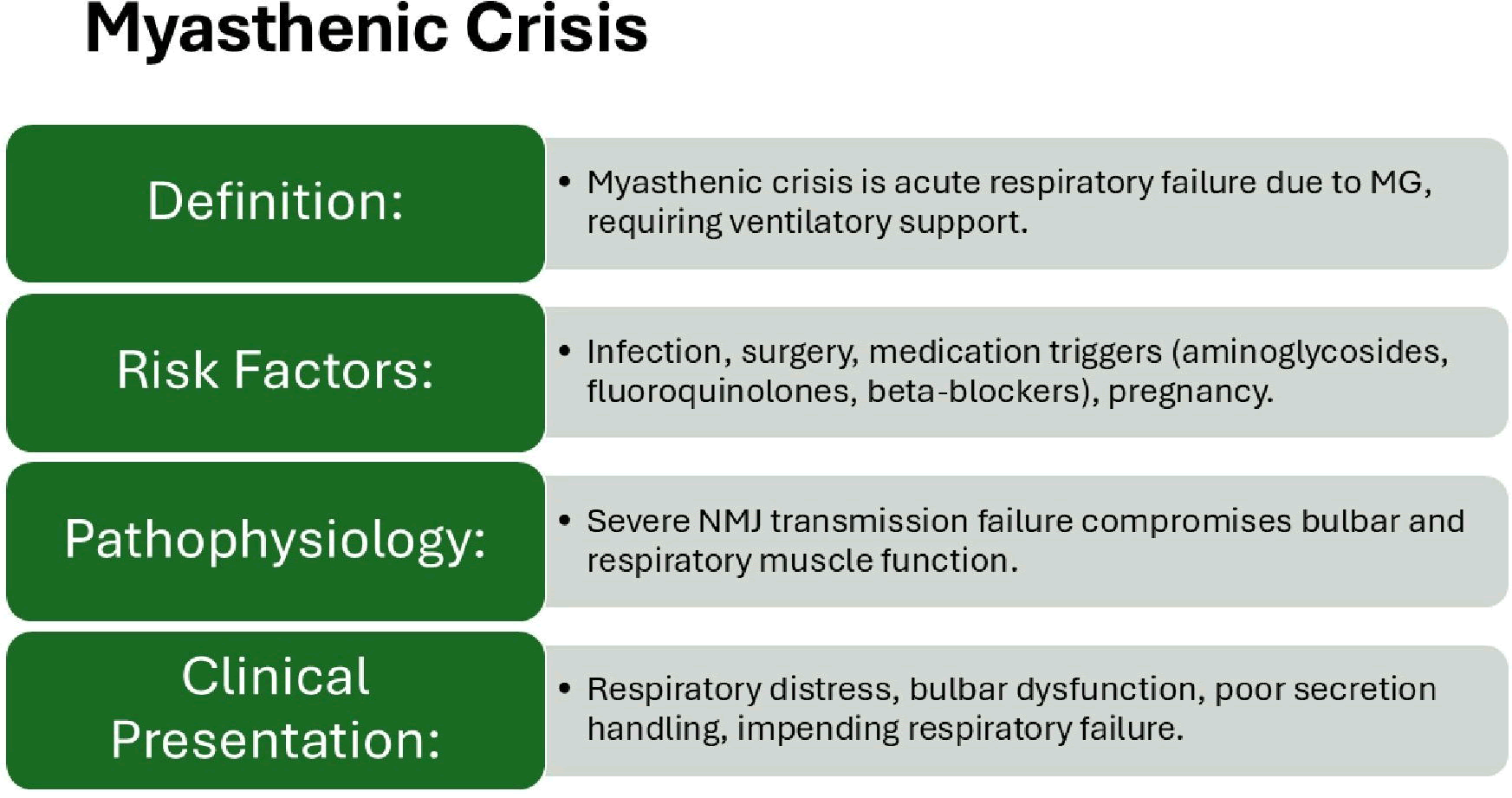

Myasthenic Crisis (MC): Contemporary management

Summary of the most relevant features of MC can be seen in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4: Clinical features

Figure 5: Other elements to consider in MC

Contemporary research has refined our understanding of crisis triggers, with respiratory infection remaining the most common precipitant, accounting for 30-40% of crises, followed by medication nonadherence and exposure to drugs that impair neuromuscular transmission [16,17].

Recent advances in critical care management of MC support the relevance of prompt diagnosis and adequate supportive care. The “20-30-40 rule” for respiratory parameters remains a helpful guideline. However, contemporary practice increasingly emphasizes the clinical assessment of bulbar function and the ability to protect the airway, as demonstrated in our case [16,17].

Contemporary therapeutic advances

The strategic therapy for MG has been significantly enhanced by novel therapeutic approaches, particularly for refractory disease. Recent developments focus on personalised treatments based on analysis of immune cells from individual MG patients. Complement inhibition with eculizumab and ravulizumab has shown rapid and sustained improvement in refractory generalised MG. FcRn antagonists such as efgartigimod represent a new therapeutic class that reduces pathogenic IgG levels, including AChR antibodies, with recent trials showing meaningful clinical improvement [18,19].

The duration of pharmacological effect of the therapeutic drugs prescribed in MG are listed in Table 2.

| Time to onset of effect | Time to maximal effect | |

| Symptomatic therapy | ||

| Pyridostigmine | 10 to 15 minutes | 2 hours |

| Chronic oral immunotherapies | ||

| Prednisone | 2 to 3 weeks | 5 to 6 months |

| Azathioprine | ~12 months | 1 to 2 years |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 6 to 12 months | 1 to 2 years |

| Cyclosporine | ~6 months | ~7 months |

| Tacrolimus | ~6 months | ~12 months |

| Antibody-based biologic therapies | ||

| Fc receptor inhibitors | ||

| Efgartigimod alfa | 2 to 3 weeks | ~4 weeks |

| Rozanolixizumab | 2 to 3 weeks | ~4 weeks |

| Complement inhibitors | ||

| Eculizumab | 2 to 3 weeks | ~4 weeks |

| Ravulizumab | 2 to 3 weeks | ~4 to 10 weeks |

| Zilucoplan | 2 to 3 weeks | ~4 weeks |

| B-cell depletion therapy | ||

| Rituximab | 4 weeks | NB weeks |

| Rapid immunotherapies | ||

| Plasmapheresis | 1 to 7 days | 1 to 3 weeks |

| Intravenous immune globulin | 1 to 2 weeks | 1 to 3 weeks |

| Surgery | ||

| Thymectomy | 1 to 10 years | 1 to 10 years |

Table 2: Shows time of onset and maximal effect of the listed medications

Clinical implications and future directions

Clinical pearls:

• Ice pack test: A Simple bedside diagnostic tool with a specificity of greater than 95% for MG when positive [11].

• Risk stratification: Young age+positive AChR antibodies+thymic abnormalities=High risk for generalization [12,13].

• Crisis prevention: Respiratory infections are the most common triggers; aggressive treatment of intercurrent illnesses is crucial [17].

• Bulbar assessment: The capacity to protect the airway and handle secretions is more critical than isolated FVC measurements [16].

• Post-thymectomy approach: Temporal worsening occurs in 10-15% of patients and should not discourage surgery [15].

Management algorithm

• Ocular phase: Establish diagnosis → Risk stratify → Consider early immunosuppression in high-risk patients [12–14].

• Generalised phase: Optimise medical therapy → Consider thymectomy → Monitor for crisis triggers [12,15].

• Crisis management: Airway protection → Immunomodulation → Gradual medication reintroduction [16,17].

The emergence of targeted biologics (complement inhibitors, FcRn antagonists) offers new hope for refractory cases. However, some instances demonstrate that traditional approaches, when applied systematically with careful attention to risk factors and clinical progression, remain highly effective for most patients [18–20].

Patient perspective

Most of our patients emphasized the importance of early education about crisis triggers and the need for immediate medical attention during respiratory infections [16,17] Figure 6.

Figure 6: Differences between MG, LEMG and botulism

Brief comments on novel drug therapy for myasthenia gravis

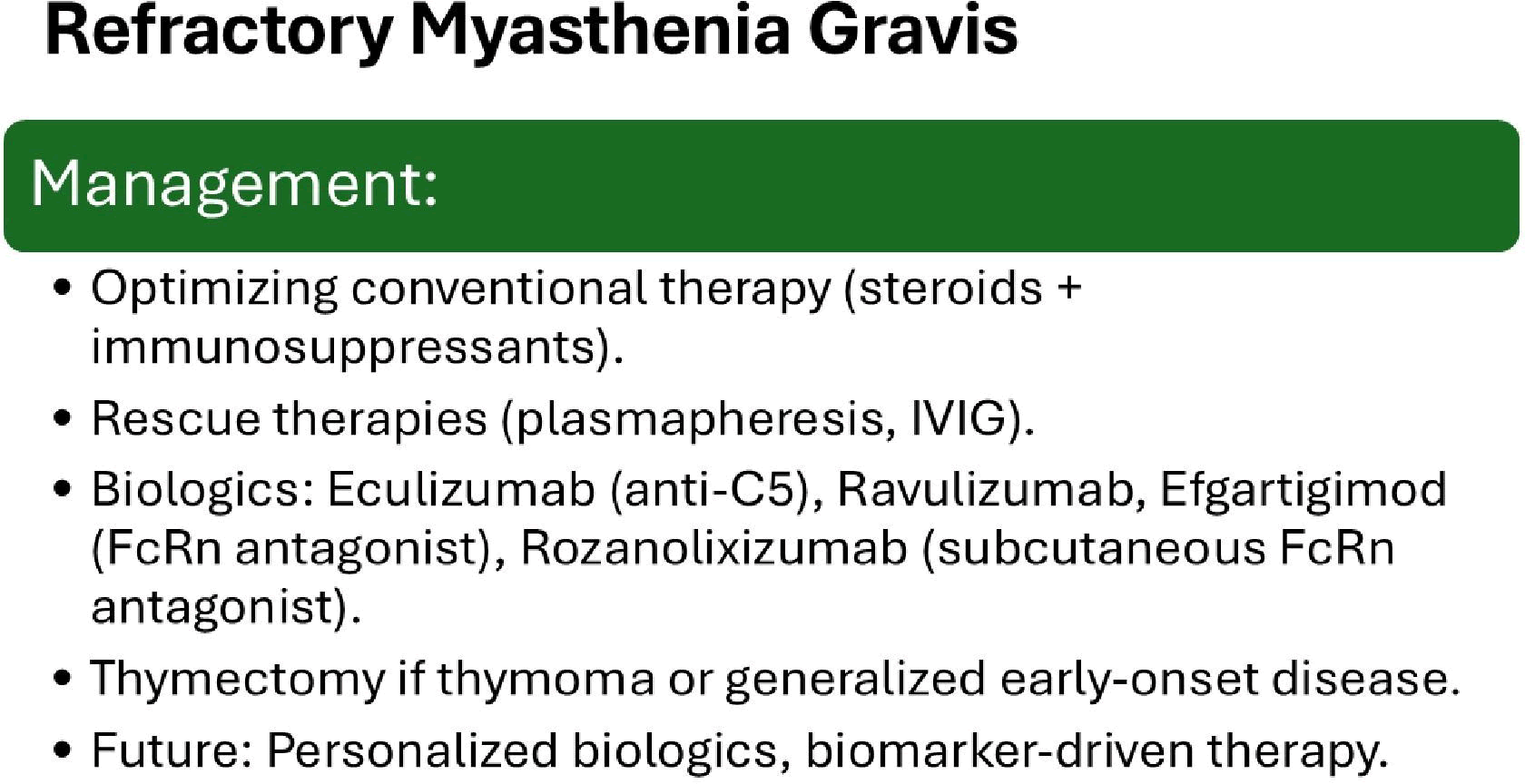

Before to comment on the novel drug therapy, it is important to summarize the most important elements to be implemented in the management of refractory MG as we represented in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Management of RMG

On the other hand, the list of novel drugs used to treat MG/ MC/RMG is shown in Table 3.

| Drug name | Indication | Characteristic | Pharmacology |

| Rituximab | gMG especially MuSK Ab + | Chimeric mouse-human anti-CD20 mAb | Depletes range of B cells |

| Zilucoplan | AChR Ab + gMG adults | Small (3.5 kDa,15 AA including four unnatural AAs) macrolytic peptide | Blocks C5 cleavage / complement cascade and C5b to C6 binding |

| CAR T cells | Adult MuSK positive 18 + | CAR T cells engineered against the MuSK autoantigen | Depletion of MuSK-specific B cells |

| Eculizumab | AChR Ab + gMG adults (Refractory in EU) | IgG2/4 kappa humanized mAb with murine CDRs | Blocks C5 cleavage and complement cascade |

| Ravulizumab | AChR Ab + gMG adults (‘Add on’ therapy in EU) | Humanized IgG4 mAb | Blocks C5 cleavage and complement cascade |

| Efgartigimod | AChR Ab + gMG adults (‘Add on’ therapy in EU) | IgG1 Fc fragment binding to FcRN | Inhibits endogenous IgG recycling via competitive FcRN blockade |

| Gefurulimab | AChR Ab + gMG adults | Bispecific miniaturized and humanized nanobody | Blocks C5 cleavage and complement cascade. Binds human albumin which increases its half-life |

| Satralizumab | Seropositive gMG 12 + years | Humanized mAb to soluble and membrane bound IL-6 receptors | Blocks IL-6 signaling and T cell activation of B cells |

| Pozelimab + Cemdisiran | AChR/LRP4 Ab + gMG adults | Stabilized human mAb to C5 with different epitope to Eculizumab/Ravulizumab, and siRNA to C5 | Blocks C5 cleavage, complement cascade and liver synthesis of complement |

| Rozanolixizumab | AChR and MuSK Ab + gMG patients | Humanized IgG4 mAb to FcRN | Inhibits endogenous IgG recycling via competitive FcRN blockade and lysosomal pathway inhibition |

| Nipocalimab | gMG adults gMG children 2–18 years | Fully human aglycosylated IgG1 mAb to endosomal and extracellular FcRN | Inhibits endogenous IgG recycling via dualcompartment FcRN blockade |

| Batoclimab | gMG adults | Fully human IgG1 mAb to FcRN with modifications to reduce cytotoxicity | Inhibits endogenous IgG recycling via dualcompartment FcRN blockade |

| Inebilizumab | AChR + MuSK + GMG adults | Humanized IgG1 anti-CD19 mAb | Depletes B cells |

| Telitacicept | gMG adults 18–80 | Fusion protein formed from TNFRSF13B and human IgG Fc receptor | Inhibits B cell activators APRIL and BAFF |

Table 3: List of novel therapeutic drug for myasthenia gravis

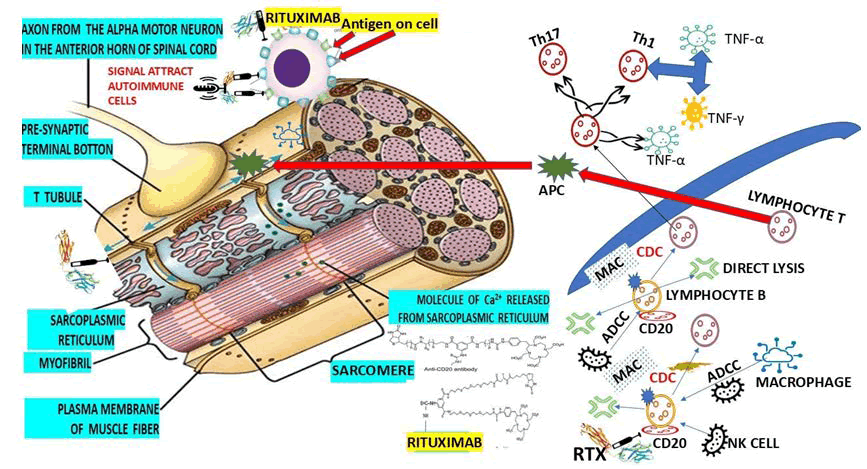

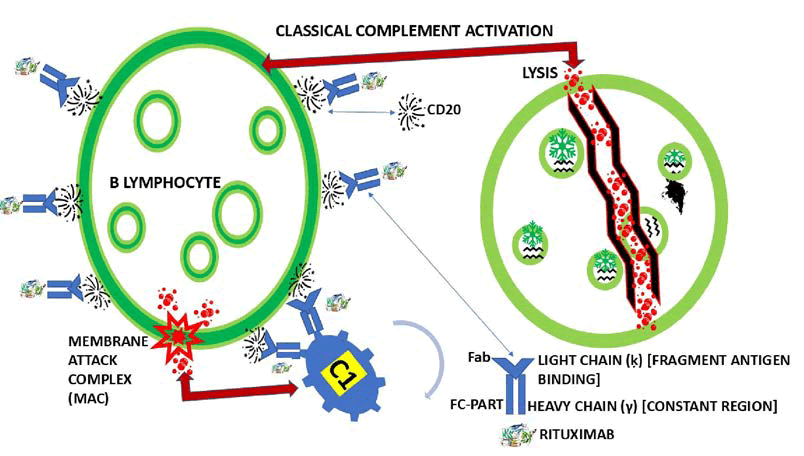

However, here we are going to highlight only the available ones in our setting. Rituximab (RTX) is the most prescribed in our region. In 2022, we published our findings using RTX in patients presenting with Refractory MG (RMG) and comorbidity of MG and polymyositis in HIV-positive patients. Our results, as well as those reported in the medical literature through a systematic review, confirm the improvement of symptoms and signs associated with MG/RMG after initiating RTX therapy. We also included two hypotheses on how the Fc portion of RTX (IgG class antibody) binds to CD20 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Show our graphical hypothesis of how the Fc portion of RTX (IgG class antibody) binds to CD20 by C1 protein at the surface of lymphocyte B leading to Membrane Attack Complex (MAC) and cytolysis.

RTX has been well tolerated in AChR-MG and MuSKMG, providing a better QOL in most patients, and at single doses not more than 500 mg can be used at the first stage of the disease instead of azathioprine and steroids. Fatal complications were not reported in those publications, and adverse reactions ranged from 26.4% to 42.8% [21,22], mainly in MUSK-MG patients (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Antigen-Presenting Cell (APC), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (VCAM1), Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β), Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNG-α), and Interferon gamma (INFγ)

Apart from successful results obtained from the drug therapy, the role played by thymectomy in MG has demonstrated an excellent response in nonthymomatous MG and is a cornerstone of MG therapy in cases with AChR antibodies. The primary modalities of treatment include complement inhibition (which drug of choices are Eculizumab, Ravulizumab, and Zilucoplan), B cell, offering Neuromuscular Junction (NMJ) protection from chronic atrophy/fatty infiltration and sustained remission in long-term MG [23]

The new reported medications for the treatment of MG will provide the best protection of the NMJ, a better therapy response in older patients, and a permanent effect on Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cells [23].

Another drug that should be highlighted is Ravulizumab (RVZ), a humanized anti-C5 monoclonal Antibody (mAb), which has demonstrated its benefits on the outcome of cases presenting generalized MG, as has been reported by other authors [24]

Another listed medication is Zilucoplan, a cyclic peptide that has the advantage of being administered Subcutaneously (SC), like Rozanolixizumab, which can target the FcRN (humanized IgG4 mAb) through the lysosomal pathway [25,26].

Also administered by SC injections, we included in Table 1: Batoclimab, a humanized IgG1 antibody targeting the FcRN. Other investigators reported respiratory tract infections (upper and lower) and peripheral oedema as the most typical side effects [27-29].

Satralizumab and Tocilizumab are both anti-IL-6 receptor mAbs that have demonstrated [30,31].

The study conducted by Ito and collaborators confirms that the early administration of zilucoplan with conventional rescue therapies for MC may have facilitated earlier extubating, thereby avoiding tacheostomy, even in patients of advanced age with associated comorbidities who face significant challenges for recovery [32].

Shahar Shelly recently reported a case with supporting evidence on acceptable safety and an excellent outcome despite presenting with MC after being treated with efgartigimod. The author also documented the effect of this novel treatment on the process of clinical stabilization before surgery and a better postoperative recovery and proposed that medication be used in cases with autoimmune MG and Eaton-Lambert myasthenic syndrome.

As has been documented, Eculizumab is an MAB blocking the terminal complement protein C5, which is very good for AChR-Ab-positive refractory generalized Myasthenia Gravis (gMG) [33].

Since some investigators reported the administration of Eculizumab in MC in 2018, other publications have revealed [34,35].

Conclusion

This comprehensive case report documents the complete clinical spectrum of myasthenia gravis in a single patient over four years, from initial ocular manifestations through generalisation to life-threatening crisis. The revised case highlights the evolving understanding of MG pathophysiology and the transformation of therapeutic approaches in recent years.

Key lessons from these revised cases include the critical importance of early recognition and risk stratification, the potential for early intervention to modify disease course, and the availability of novel targeted therapies for refractory cases. The journey of our patient-from a young woman struggling with drooping eyelids during study sessions to surviving a life-threatening crisis and achieving stable disease control-exemplifies both the challenges and remarkable therapeutic opportunities available in contemporary MG care.

Ethics Statement

This review does not require ethical approval.

Patient Privacy

All patient-identifying information has been removed to ensure anonymity.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

Authors of this review declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- A-M. Bubuioc, A. Kudebayeva, S. Turuspekova, V. Lisnic, M.A. Leone, The epidemiology of myasthenia gravis, J Med Life, 14(2021):7-16.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. Dresser, R. Wlodarski, K. Rezania, B. Soliven, Myasthenia gravis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical manifestations, J Clin Med, 10(2021):12235.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E. Rodrigues, E. Umeh, A. Aishwarya, N. Navaratnarajah, A. Cole, et al. Incidence and prevalence of myasthenia gravis in the United States: A claims-based analysis, Muscle Nerve, 69(2024):166-171.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Ye, D.J. Murdock, C. Chen, W. Liedtke, C.A. Knox, Epidemiology of myasthenia gravis in the United States, Front Neurol, 15(2024):1339167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.J.G.M. Verschuuren, J. Palace, N.E. Gilhus, Clinical aspects of myasthenia explained, Autoimmunity, 43(2010):344-352.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- N.E. Gilhus, S. Tzartos, A. Evoli, J. Palace, T.M. Burns, et al. Myasthenia gravis, Nat Rev Dis Prim, 5(2019):1-19.

- W.D. Phillips, A. Vincent, Pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis: Update on disease types, models, and mechanisms, F1000Res, 5(2016).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Hong, P. Zisimopoulou, N. Trakas, Multiple antibody detection in “seronegative” myasthenia gravis patients, Eur J Neurol, 24(2017):844-850.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Grob, N. Brunner, T. Namba, M. Pagala, Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis, Muscle Nerve, 37(2008):141-149.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L.L. Kusner, A. Puwanant, H.J. Kaminski, Ocular myasthenia: Diagnosis, treatment, and pathogenesis, Neurologist, 12(2006):231-239.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- K.C. Kubis, H.V. Danesh-Meyer, P.J. Savino, R.C. Sergott, The ice test versus the rest test in myasthenia gravis, Ophthalmology, 107(2000):1995-1998.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- P. Narayanaswami, D.B. Sanders, G. Wolfe, International Consensus Guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: 2020 update, Neurology, 96(2021):114-122. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.J. Kupersmith, R. Latkany, P. Homel, Development of generalized disease at 2 years in patients with ocular myasthenia gravis, Arch Neurol, 60(2003):243-248.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C. Schneider-Gold, P. Gajdos, K.V. Toyka, R.R. Hohlfeld, Corticosteroids for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2005(2):CD002828.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- G.I. Wolfe, H.J. Kaminski, I.B. Aban, Long-term effect of thymectomy plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in patients with non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis: 2-year extension of the MGTX randomised trial, Lancet Neurol, 18(2019):259-268.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L.C. Wendell, J.M. Levine. Myasthenic crisis, The Neurohospitalist, 1(2011):16-22.

- R.R. Gummi, N.A. Kukulka, C.B. Deroche, R. Govindarajan. Factors associated with acute exacerbations of myasthenia gravis, Muscle Nerve, 60(2019):693-699.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.F.J. Howard, V. Bril, T.M. Burns, Randomized phase 2 study of FcRn antagonist efgartigimod in generalized myasthenia gravis, Neurology, 92(2019):e2661-e2673.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- V. Bril, M. Benatar, H. Andersen, Efficacy and safety of rozanolixizumab in moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis: A phase 2 randomized control trial, Neurology, 96(2021):e853-e865.

- F. Piehl, A. Eriksson-Dufva, A. Budzianowska, Efficacy and safety of rituximab for new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis: The RINOMAX randomized clinical trial, JAMA Neurol, 79(2022):1105-1112.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lourdes de Fátima Ibañez Valdés, Sibi Sebastian Joseph, Humberto Foyaca Sibat, Rituximab in refractory myasthenia gravis: A systematic review, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- Lourdes de Fátima Ibañez Valdés, Sibi George, Humberto Foyaca Sibat, Comorbidity of polymyositis and myasthenia gravis in HIV patients treated with rituximab, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- S.N.M. Binks, I.M. Morse, M. Ashraghi, A. Vincent, P. Waters, et al. Myasthenia gravis in 2025: Five new things and four hopes for the future, J Neurol, 272(2025):226.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- T. Vu, A. Meisel, R. Mantegazza, Terminal complement inhibitor ravulizumab in generalized myasthenia gravis, NEJM Evid, 1(2022):1-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B. Smith, A. Kiessling, R. Lledo-Garcia. Generation and characterization of a high-affinity anti-human FcRn antibody, rozanolixizumab, and the effects of different molecular formats on the reduction of plasma IgG concentration, MAbs, 10(2018).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- V. Bril, A. Drużdż, J. Grosskreutz, Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, adaptive phase 3 study, Lancet Neurol, 22(2023):383-394.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C. Yan, Y. Yue, Y. Guan, Batoclimab vs. placebo for generalized myasthenia gravis: a randomized clinical trial, JAMA Neurol, 81(2024):336-345.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- V. Bril, A. Drużdż, J. Grosskreutz, Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, adaptive phase 3 study, Lancet Neurol, 22(2023):383-394.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Piehl, A. Eriksson-Dufva, A. Budzianowska, Efficacy and safety of rituximab for new-onset generalized myasthenia gravis: The Rinomax randomized clinical trial, JAMA Neurol, 79(2022):1105-1112.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Jia, F. Zhang, H. Li, Responsiveness to Tocilizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor-positive generalized myasthenia gravis, Aging Dis, (2024).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.L. Bennett, K. Fujihara, H.J. Kim, SAkuraBONSAI: Protocol design of a novel, prospective study to explore clinical, imaging, and biomarker outcomes in patients with AQP4-IgG-seropositive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder receiving open-label satralizumab, Front Neurol, (2023).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Ito, T. Sugimoto, H. Naito, S. Aoki, M. Nakamori, et al. Zilucoplan for successful early weaning from mechanical ventilation and avoiding tracheostomy in an 85-year-old woman experiencing myasthenic crisis: A case report, Cureus, 17(2025):e80203.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Shelly, Case report: Successful perioperative intervention with efgartigimod in a patient in myasthenic crisis, Front Immunol, 16(2025):1524200.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Crescenzo, M. Zanoni, L. Ferigo, F. Rossi, M. Grecò, et al. Eculizumab as Additional Rescue Therapy in Myasthenic Crisis, Muscles, 3(2024):40-47.

- C.J. Yeo, M.Y. Pleitez, Eculizumab in refractory myasthenic crisis, Muscle Nerve, 58(2018):E13-E15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Copyright: © 2025 Joseph Sibi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.