Research Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2025) Volume 14, Issue 11

Update Information on Locked-In Syndrome, Drug Therapy and Comprehensive Review

Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes1* and Humberto Foyaca Sibat22Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes, Department of Neurology, Walter Sisulu University (WSU), South Africa, Email: humbertofoyacasibat@gmail.com

Received: 22-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-171195; Editor assigned: 24-Sep-2025, Pre QC No. JDAR-25-171195 (PQ); Reviewed: 08-Oct-2025, QC No. JDAR-25-171195; Revised: 12-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-171195 (R); Published: 19-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236479

Abstract

Introduction: Locked‐in Syndrome (LIS) is characterised by anarthria, cranial nerve palsies, and quadriplegia, with a normal level of consciousness, awareness without cognitive decline, regular eyelid movements, preserved vertical gaze movements, hearing, and proper breathing. In patients with LIS, cognitive function may be affected, depending on the nature of the lesion; the brainstem is the most common post‐injury site, while awareness and arousal remain intact.

Objectives: This comprehended literature study aimed to search for studies related with the emerging and novel therapies for LIS.

Methods: We search the EMBASE, Scopus, and Medline, databases, to identify case reports, case series, clinical trials in patients of any sex, race, age, or ethnicity who received any approved or experimental treatment for LIS. From 01st, January 2013 to 30th, September 2025, we searched the medical literature, following the PRISMA guidelines. the authors searched the scientific databases, Scopus, Embassy, Medline, and PubMed Central using the following searches: “Locked‐in syndrome” OR “Legal rights” OR “Legal implications” OR “Aetiology LIS” OR “Pathogenesis of LIS”, OR “Assessment of consciousness” OR “Communication methods” OR “Communication abilities” OR “Assessment of consciousness” OR “Emerging invasive communication methods” OR “Brain‐computer interfaces” OR “Drug therapy”.

Results: After screening the publications for relevance, n=649 qualified articles were identified. Included for the first screen n=6. Records after duplicates removed n=384, record included for full‐test review n=265. Excluded by full‐test review n=97 studies. Additional reports after search by identified references (covering 77 studies) n=9. No article proposing a therapeutic drug for LIS as found when we searched. Therefore, meta‐analysis was not done.

Conclusions: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review done proposing an update drug therapy program for LIS based on previous results obtained from Mc therapy modalities.

Keywords

Locked-in state; Complete locked-in state; Color vision deficiency; Assessment of consciousness; Communication abilities; Communication methods; Emerging invasive communication methods

Introduction

The world-famous book “The Count of Monte Cristo” is written by Alexandre Dumas in 1844, based on the real-life man Pierre Picaud, who was unjustly imprisoned on false accusations, much like Edmond Dantes. In this literature jewel the author described: “Sight and hearing were the only senses remaining, and they, like two solitary sparks, remained to animate the miserable body which seemed fit for nothing but the grave; it was only, however, by means of one of these senses that he could reveal the thoughts and feelings that still occupied his mind, and the look by which he gave expression to his inner life was like the distant gleam of a candle which a traveller sees by night across some desert place, and knows that a living being dwells beyond the silence and obscurity” [1]. As it’s well remembered, after Edmond Dantes recovered his buried treasure, he returned to Paris to take revenge on his three jealous friends implicated in this conspiracy. Almost one century later (1966), Plum and Posner described the Locked-in Syndrome (LIS) [2]. These authors reported: “is a specific neurobehavioral diagnosis that refers to patients who are alert, cognitively aware of their environment, and capable of communication but cannot move or speak” [2]. This condition has been described as “buried alive” by Khanna et al. in 2011 because the brain’s patient can function adequately in a nonfunctional body completely limited by lack of speech and voluntary movements, like a person trapped or imprisoned within its own body, as has been documented by other investigators [3,4].

Jean-Dominique Bauby was a 43-year-old former editorin-chief of the French magazine Elle. On December 8th, 1995, he developed an ischemic stroke while driving a car with his son to a night out at the theatre. Twenty days later, he woke up in the hospital with complete paralysis of his limbs, unable to talk. Unfortunately, he could only blink his left eyelid after a brainstem stroke, developing a LIS and sparing the higher cerebral functions. After that, by blinking his left eye, he wrote about “The diving bell and the butterfly,” based on his remarkable true story, in his memoir of this experience, describing it as “Something like a giant invisible diving bell holds my whole-body prisoner.” [5].

Classically, LIS is characterised by anarthria, cranial nerve palsies, and quadriplegia, with a normal level of consciousness, awareness without cognitive decline, regular eyelid movements, preserved vertical gaze movements, hearing, and proper breathing. In patients with LIS, cognitive function may be affected, depending on the nature of the lesion; the brainstem is the most common post-injury site, while awareness and arousal remain intact [6].

In 1959, Adams and collaborators described, for the first time, a bilateral and symmetrical demyelinating process in the central region of the pons in a 38-year-old male patient with a past medical history of chronic ethanol consumption [7].

On the other hand, Hordila and collaborators have documented three modalities of LIS according to their range of motility, grouped as:

• Classic, when the patient is alert and eye movements are present.

• Partial/ incomplete, when residual active movements apart from ocular motility and the patient is awake.

• Total/global, when a patient is completely paralysed, including ophthalmic paralysis, but is fully conscious clinically or confirmed by electroencephalogram.

In summary, total LIS is reported as a complete paralysis, including loss of vertical eye movements. At the same time, incomplete/partial LIS is classically characterised by an addition of voluntary movements or some ocular muscular function aside from conjugate up-gaze.

Apart from central pontine demyelination, other pathological conditions have been reported as the principal cause of LIS, including traumatic posterior fossa injury, stroke, degenerative disorders, and brainstem malignancies. In anecdotal cases, a bacterial infection caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi can be an underlying cause of LIS [8].

The prevalence of LIS has been estimated between 0.17/10,000 and <1/1000,000 [9].

In 2013, a survey in Dutch nursing homes showed a prevalence of 0.7/10,000 people [10]. Polhemus et al. reported a 33-year-old lady with a longstanding history of systemic lupus erythematosus presenting and two-week history of headache, fever, vomiting due to posterior and central pons with oedema leading to partial LIS [11].

In 2024, Ankolekar and collaborators report an old lady presenting a brainstem stroke with pseudo-bulbar palsy during recovery from LIS [12].

It has been established that most often the aetiology of fatal sporadic encephalitis in the United States is HSV-1 Encephalitis (HSE) caused by reactivation of HSV in the brain leading to tissues necrosis and neurological manifestations including fever, seizures, altered mentation, and focal neurological signs due to severe damage of the temporal lobe or more rarely the cerebellum and brainstem. The last one can be presented as brainstem encephalitis causing quadriplegia or locked-in syndrome [13].

Krim and colleagues reported a 52-year-old man presenting with a LIS associated with pan-neurofascin autoimmune nodoparanodopathy with a good prognosis [14].

During the last century, patients with LIS had to communicate with others through gaze and facial movements. Fortunately, in recent times, some devices for communication and control without any muscular input have been developed thanks to technological advancements, creating a brain-computer interface or BCIs among other game-changers, which have a remarkable impact on the lives of people with LIS, helping them improve their quality of life and restoring their way of communication [15].

A locked-in state has been reported in patients with advanced stages of motor neuron disease (ALS) [16].

The Norwegian national unit for rehabilitation of LIS has established that all diagnosed patients must be reported to their unit. Therefore, they have the capacity to register all cases countrywide. The population of Norway is around of 5.5 million inhabitants where fifty-one LIS cases lasting more than 6 weeks were confirmed [17].

In 2015, a group of investigators assessed changes in QoL in an LIS population over 6 months and found different results, but most patients with preserved communication lived as normally as possible. They recovered oral and reading comprehension, spatial orientation, correct– left discrimination, short-term memory, intellectual functioning, and visual recognition; notwithstanding, a significant number of cases suffered from impairments for distractibility, impulse control, mental calculation, problem solving, complex sentence comprehension, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and executive functioning [18].

Li et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey using a selfadministered questionnaire among Chinese neurologists from August 2018 to December 2019 to obtain more detailed information on the management of LIS. They found that more specific LIS education is necessary [19].

In 2023, Vaithislingsm et al. reported a 60-year-old female presenting with a subarachnoid/intraventricular haemorrhage secondary to a broken of congenital aneurysm at the internal carotid artery, with a history of arterial hypertension, experienced a comatose stage with mydriasis upon admission. This lady responded with eye blinking and vertical gaze movements, and LIS was diagnosed [20]. This report was also commented on by Finsterer [21].

Another rare cause of LIS was reported by Heinz et al. regarding a 37-year-old lady with a standing history of amphetamine consumption leading to a pontine haemorrhage with fourth ventricle invasion [22].

In 2024, Wrenn et al. reported for the first time in the medical literature a 54-year-old male who underwent C4-C7 left-sided cervical posterior foraminotomy successfully, leading to a left vertebral artery dissection, basilar artery occlusion, and pontine ischemic stroke followed by LIS [23].

Last year, Barakat and colleagues reported an anecdotal case of a stressful situation in which an anaesthesia team attempted to provide safe anaesthetic care to a patient presenting with LIS due to communication barriers, resulting in a severe impact on the patient-anaesthesiologist relationship [24].

Sinha et al. reported a 30-year-old male with a novel association between caffeine supplements and energy drinks leading to the swift onset of stroke followed by LIS [25].

One of the rare demyelinating diseases affecting the pons is the Central Pontine Myelinolysis (CPM), which can cause LIS. Chabert and colleagues described the outcome over 12 months of two cases presenting with LIS due to CPM. Both patients showed progressive improvement at 2 and 3 months after the onset of their clinical features, achieving almost total autonomy after 1 year, with the disappearance of the demyelinating pontine lesions confirmed by cerebral MRI with tractography. These authors also documented that reversible myelin injury in partially pontine neurons, resolution of conduction in the blocked pathway, and the development of collateral pathways can lead to clinical recovery [26].

Materials and Methods

A literature review was conducted using the databases PubMed and Scopus, covering the period between 2013 and 2023.

Search strategy

We searched the medical literature based on the PRISMA guidelines.

Following the PRISMA guidelines, we search the EMBASE, Scopus, and Medline, databases, to identify case reports, case series, clinical trials in patients of any sex, race, age, or ethnicity who received any approved or experimental treatment for LIS.

From 01st, January 2000 to 30th, September 2025, we searched the medical literature, following the PRISMA guidelines. the authors searched the scientific databases, Scopus, Embassy, Medline, and PubMed Central using the following searches: “Locked-in syndrome” OR “Legal rights” OR “Legal implications” OR “Aetiology LIS” OR “Pathogenesis of LIS”, OR “Assessment of consciousness” OR “Communication methods” OR “Communication abilities” OR “Assessment of consciousness” OR “Emerging invasive communication methods” OR “Braincomputer interfaces” OR “Drug therapy”.

Selection criteria

The following criteria were included:

Articles with detailed pathogenesis and/or drug management. Clinical features of LIS, and demographic information.

Exclusion criteria were applied:

• Inaccessibility to full text.

• Articles with unclear pathogenesis.

• Lack of relevant clinic pathological data.

• Non-original studies (i.e., editorials, letters, conference proceedings, book chapters).

• Animal model studies.

• Non-/Spanish/Portuguese/English studies.

The papers that were not thoroughly assessed were removed.

Data collection, extraction, and bias assessment

All abstracts and titles with the inclusion criteria were selected by a single reviewer. The selected data from eligible publications were introduced into an updated Excel software program. Extracted data included the study design, clinical features of patients, baseline demographics, length of follow-up, treatment details, outcomes of interest, funding information, and final remarks.

Data extraction and quality assessment

As mentioned before, all the included data were processed in an electronic Excel database. The studies’ quality was categorized as good, poor, fair, or reasonable, in agreement with the National Institutes of Health criteria.

Outcome measures

Our plan aimed to select the most relevant publications relating to the clinical benefit and real-world effectiveness of different therapies for LIS. This investigation also identified safety outcomes data, including adverse and serious adverse events across the clinical investigations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT (add-on for Microsoft Excel, version 2021.4.1, Addinsoft SARL) and RStudio (version 4.3.1, https://www.rstudio.com/). Variations in continuous variables were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. We presented descriptive statistics for continuous variables as median (95% Confidence Interval (95% CI)).

Results and Disussion

After screening the publications for relevance, n=649 qualified articles were identified. Included for the first screen n=6. Records after duplicates removed n=384, record included for full test review n=265. Excluded by full test review n=97 studies. Additional reports after search by identified references (covering 77 studies) n=9. No article proposing a therapeutic drug for LIS as found when we searched. Therefore, meta analysis was not done.

Comments and final remarks

The main aetiologies and pathogenesis of LIS are listed below in Table 1.

| Aetiology | Pathophysiology |

| Traumatic | Direct brain stem contusion or vertebrobasilar axis dissection |

| Haemorrhage | Haemorrhage originating within or infiltrating into the pons |

| Metabolic | Central pontine myelinolysis |

| Demyelination | Multiple sclerosis affecting the ventral pons |

| Infectious | Abscess infiltrating the ventral pons, brain stem encephalitis |

| Ischaemic | Basilar artery occlusion, hypotensive or hypoxic events |

| Tumour | Primary or secondary infiltration of the ventral pons |

Table 1: Main aetiologies and patophysiology of LIS

Brief comments on Central Pontine Myelinolysis (CPM)

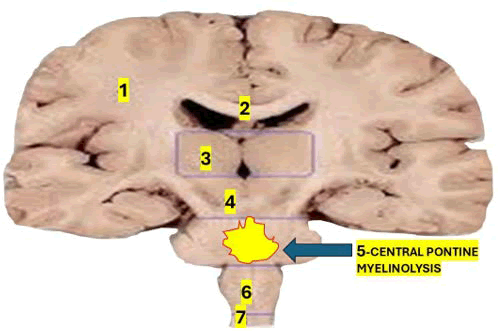

As mentioned before, CPM is an uncommon demyelinating disorder that affects the pontine region of the brainstem, causing LIS in the initial phase [27,28]. Another aetiology of CPM is the fast correction of hyponatremia [29]. The commonest affected area of demyelination at the pontine level is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Shows the affected area in cases presenting CPD. 1) Coronal radiata; 2) Corpus callosum; 3) Thalamic nucleus; 4) Midbrain; 5) Pons; 6) Medulla oblongata; 7) Spinal cord

This situation leads to endothelial damage, disruption of the BBB, and intracellular dehydration, exposing glial cells to complement and cytokines, which in turn trigger oligodendrocyte apoptosis and myelin degradation [30,31].

Because astrocytes and microglia are resistant to osmotic stress, only oligodendrocytes are directly affected by osmotic demyelinating syndrome caused by a rapid correction of hyponatremia, which affects mainly the central pons region. However, other areas can be involved in (Extrapontine Myelinolysis, EPM) [32,33].

However, CPM can be seen in cases without any rapid correction of hyponatremia when some intrinsic favouring factors are present, such as electrolyte disorders, type II diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, malignancies, malnutrition, chronic liver diseases, and other chronic systemic disorders [26].

The clinical feature of CPM is characterised by a double phase consisting of encephalopathy due to hyponatremia leading to lower motor neuron signs, headache, myalgias, and general malaise, among other complaints, followed by a gradual recovery. The second phase is characterised by neurological manifestations such as ataxia, affected levels of consciousness, weakness or paralysis, dysarthria, LIS, or even a fatal outcome. Despite the previously mentioned cases with good prognosis and complete recovery, the prognosis is generally relatively poor [26].

Brief comments on Colour Vision Deficiency (CVD) in LIS

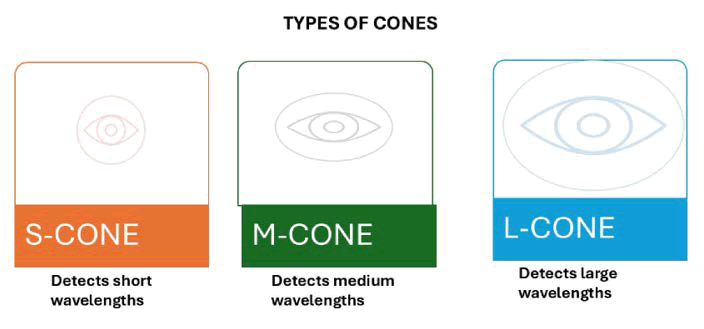

The inability to differentiate colours in standard lighting is a common visual impairment among people with dysfunctional three cone colour photoreceptors in the tenth layer of the retina, which absorb photons. Now, the most used diagnostic test to investigate this problem requires behavioural and communication abilities/participation; therefore, this procedure is unsuitable for people with LIS. However, this year, AlEssa and Alzahrani developed a new non invasive procedure that analyses brain waves using Steady State Visually Evoked Potentials (SSVEPs) to confirm CVD. As is well known, each cone photoreceptor in the macula is sensitive to a specific region of the visible spectrum; these cones cover a range of wavelengths associated with colour hues [34]. The differences among the three main kinds of cones are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Represent the ranges of the cones in the visible spectrum overlap, requiring complex computations by the brain to accurately recognize the correct hue. There are three main types of cones: The S-cone, which detects short wavelengths; the M-cone, which detects medium wavelengths; and the L-cone, which detects long wavelengths. The ranges of the cones in the visible spectrum overlap, requiring complex computations by the brain to accurately recognize the correct hue

The brain waves recorded via SSVEP can provide remarkable insights into colour perception at different stages, initially from the detection of the wavelength, followed by its brain decoding by comparing the overlapping spectra of different cones to identify the correct colour [35].

Notwithstanding, if one of the mentioned cones fails to detect a wavelength, the signal fails to reach the brain, affecting the decoding mechanism and leading to an inability to identify the specific colour [36].

According to the type of affected cone, genetic CVDs can be divided into two groups (trichromacy and dichromacy), which can further be subdivided into protanomaly (abnormal L cone), deuteranomaly (abnormal M cone), and tritanomaly (abnormal S cone). On the other hand, dichromacy comprises protanopia (loss of the L cone), deuteranopia (loss of the M cone), and tritanopia (loss of the Scone) [37]. The most frequent procedures for diagnosing CVD include the anomaloscope, the Farnsworth–Munsell (FM) 100 hue test, and the Ishihara test [38], which are not suitable for people with language/ speech disabilities, involuntary movements, or abnormal behaviour. Particularly, SSVEP is one of the most confident tests based on its capacity to analyse the responses of the neurons from the primary visual cortex when exposed to recurrent visual stimulation at specific frequencies, being quite effective for identifying EEG changes in response to a variety of colours because of its elevated signal noise ratio and highly decreased susceptibility to noises/artefacts [39].

In conclusion, AlEssa and Alzahrani recommended SSVEP as the best choice to diagnose CVD in patients with LIS [34].

Brief comments on the assessment of consciousness in LIS

To support a reduction misinterpretation on diagnosis and clinical terminology, we are highly below our recommended guideline.

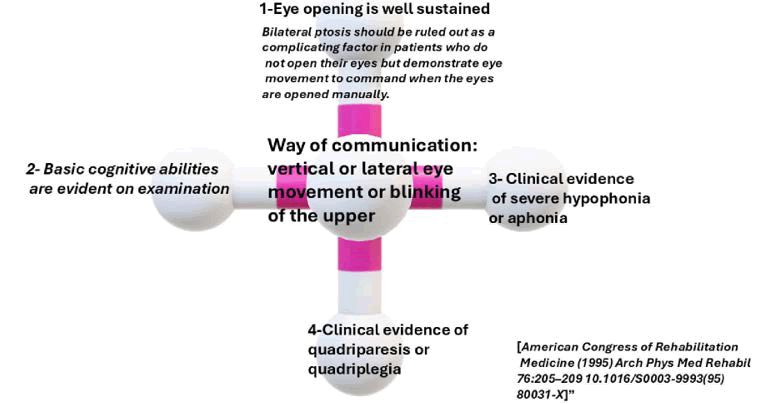

To diminish controversies and confusion on the use of LIS and other diagnostic and clinical terms assigned to patients with severe alterations in consciousness, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) presented the following neurobehavioral criteria as the biomarker for diagnosing LIS:

• Eye opening is well sustained (bilateral ptosis should be ruled out as a complicating factor in patients who do not open their eyes but demonstrate eye movement to command when the eyes are opened manually).

• Basic cognitive abilities are evident on examination.

• There is clinical evidence of severe hypophonia or aphonia.

• There is clinical evidence of quadriparesis or quadriplegia.

• The primary mode of communication is through vertical or lateral eye movement or blinking of the upper eyelid.

The first assessment in LIS patients is to confirm the level of consciousness by assessing the patient’s capacity to obey commands, their responses to external stimuli, and their behaviours to determine the reliability of their yes/no responses, using eye movements if other muscle activity is absent.

Nevertheless, it’s crucial to consider the people’s ability to communicate, age, and premorbid conditions.

As previously cited, patients with LIS maintain normal levels of consciousness and cognitive function. To achieve the best QOL for LIS cases, it is essential to enhance their capacity to communicate with others and interact with their environment, which brain computer interfaces facilitate. In our opinion, the crucial condition for achieving that goal is maintaining a normal level of consciousness. Recently, Adama et al. documented a novel approach to analysing the brain waves recorded by an EEG to assess the level of consciousness in LIS patients and they found that their approach was practical in identifying neural markers of wakefulness and in differentiating among states across most patients by extracting several features based on complexity, frequency, and connectivity measures to increase the probability of correctly determining the patients’ actual states.

The consciousness levels obtained from this approach helped achieve a better understanding of the patients’ condition, which is essential for an accurate communication system [40].

In conclusion, EEG is a crucial procedure for assessing brain activity and communication abilities by recording brain cortical electrical activity, providing insights into brain function. Although EEG has lower spatial resolution than CT and MRI, it offers higher temporal resolution, enabling real time communication [41].

As will be discussed below in more detail, EEG signals integrated into BCIs can provide better control of external devices, answer yes or no questions, and spell words by modulating the brain’s electrical activity despite noise and individual physiological variations [41].

Brief comments on legal issues in LIS

People with LIS may face serious legal challenges because they have paralysis of the limbs and many cranial nerves despite their preservation of consciousness, visual perceptions, and cognitive functions, which only allow them to communicate with extreme limitations without restricting all legal rights.

(Research for this article was carried out in the framework of the project Anthropology and Phenomenology of the Locked-in Syndrome, which the author coordinates at the Medical Anthropology Research Centre, Anthropology Department, Rovira i Virgili University (Tarragona, Spain). All URLs were checked on September 30, 2025). Nevertheless, some authors have reported cases of people with LIS fighting for their rights despite those limitations, in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [16].

People suffering from LIS retain the capacity to make personal decisions based on their normal level of consciousness and cognition. Therefore, they can assume responsibility, respond for their choices and commitments and make acts of legal and civil import including claiming for their patients’ rights, voting in political elections, make agreements, decide for own therapy preferences, and even owning property if they have the necessary support for express their will supported by an adequate cognition, volitional faculties and the possibility to act and express one’s will in a way of showing individual autonomy [42].

Fortunately, the Spanish civil code was adopted in 2021 from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD-2006), to support the necessary human assistance that sufficed to justify a locked in person’s incapacitation (blocking the right to exercise legal capacity), despite their cognitive abilities. Before, the court would place LIS patients under tutela (guardianship), a situation in which a court appointed ward would act on behalf of the patient for all acts requiring legal capacity. The CRPD 2006 above established that the convention must remove all substitute decision making states “to ensure that full legal capacity is restored to persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others” [43].

Despite CRPD insisting on the application to all peoples of the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”—which includes the complete suppression of substitute decision making, remains a subject of discussion, and not all convention’s signatories have moved in that pathway.

This article’s main goal was to consider, through legal cases, what led judges to incapacitate patients with LIS and the circumstances in which some of those patients recovered their civil rights. The project revealed deeply rooted, interrelated views on legal capacity, individual autonomy, legal personhood, communication, and technology.

As we described above, the principal ways of communication between LIS patients and other people include eye movement to call attention or blinking, respond to yes/no questions, spell and construct simple sentences by choosing vowels and consonants from an alphabetical panel, or, even better, through a computer based eyetracking system [44].

The main advantage of employing an Alternative Communication (AAC) system and high tech augmentative is their capacity to process information from even minimal preserved or recovered motor activities [45,46].

Therefore, this procedure helps patients with brain implants, incomplete LIS, and Brain–Computer Interfaces (BCIs) to use communication services independently of their range of muscular activity [15].

We mentioned two LIS cases that were deprived of their rights and placed under the custody of a tutor (plenary guardianship) in a program of full substitute decisionmaking. Later, they attempted to recover active legal personhood. However, one of them could communicate by himself using a computer and reached his civil rights based on the judge’s assumption of the capacity of selfgovernance without intersubjective mediation supported by the Spanish civil code after being adapted to the convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [16] and the Spanish Democratic Constitution (1978) which establish that “Public authorities shall carry out a policy of preventive care, treatment, rehabilitation and integration of the physically, sensorially and mentally handicapped” protecting them and delivering the condition to “reach the legal capacity on an equal basis with others”.

Later, other LIS cases involved in legal fights to recover their civil rights to vote and make a will failed because current legal systems require proof of volitional and cognitive capacity, as well as the subject’s ability to externalise or express their will and choices in an accurate way that can be easily confirmed. Therefore, three interconnected issues must be present. Unfortunately, there is no political or scholarly consensus about the total elimination of substitute decision making and guardianship regimes at present, despite the CRPD’s opinion and the criteria of signatories. Therefore, how to manage the civil rights of LIS patients remains unclear and is still at the heart of judicial decisions.

Recently, Jude and colleagues decoded intended speech from people suffering from severe inability to talk, characterised by a complete failure to articulate spoken language, advanced motor neuron disease (ALS) with permanent ventilator dependence. LIS found that words, phonemes, and units of higher order language can be appropriately decoded above chance confirming an extensive characterization of the neural signals underlying speech and the chance of provide new ways of forthcoming improvement including decoding linguistic (rather than phonemic) units and closed loop speech imagery training from neural signals in middle of the primary motor cortex (precentral gyrus) even in patients with permanent dependence to the ventilatory machine [47].

Brief comments on communication abilities in LIS

A crucial element in maintaining or improving QOL for people with LIS is the restablishment of an accurate communication system.

The ways of communication of LIS patients are graphically listed in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The image provides criteria for diagnosing LIS, focusing on eye opening, communication, cognitive abilities, and clinical evidence of quadriparesis

Since 2016, Vansteensel et al. introduced a world first entirely procedure to recover the communication between LIS patients and their environment through implantable Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs) using subdural Electrocorticography (ECoG) electrodes to perform a brain signal recording amplified subcutaneously and transmitted to the surrounding space, giving these patients the possibility to communicate with other people via a computer by processing icons in spelling software. In 2022, based on their own experience and a medical literature review, they delivered an overview of recommendations, procedures, screening, inclusion, imaging, hospital admission, implantation, training, recruitment, and support for participants with LIS for implantable BCIs [48].

Brief comments on communication methods

Last year, Voity and colleagues studied the role of communication ability in QOL in LIS cases by evaluating cognition. They reported the best way to improve communication learning abilities, how to manage those abilities, and an update on current procedures to improve communication in LIS cases [44].

The communication procedure can be divided into three different groups: High tech, low tech, and no tech alternative and augmentative communication. The last one does not require supplementary materials to obtain information from ocular movements (looking right left or up down), blinking, facial muscle contraction, or limb movements on command [44]. In no tech communication, procedures are employed, and each movement serves a specific communicative purpose [48].

Low-tech augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) can be implemented according to the cognitive function and people’s eye movements using pencil, pen, paper, letter board or single-message voice output devices like BigMac [49]. In case of using letter board (EyeLink board or Eye Transfer Board) in LIS patients with accurate eyes movement, it could be a confident way of communication by selecting cluster of letters or even single letters through blinking, other way of personal means of selection or fixation [50].

The best communication procedure implies the use of hightech AAC supported by tablets or PC with the capacity to integrate eye tracking, eye-gaze switches, or eye-gaze devices able to control those previously cited electronic devices to communicate adequately. In addition to eye-gaze devices, another procedure involves a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) [51].

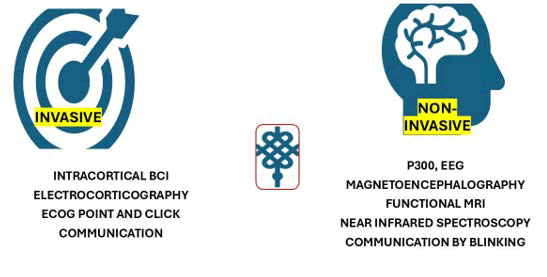

The most relevant invasive and non-invasive procedures for communication can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Represent the most important invasive and non-invasive ways of communication

In addition to using eye-gaze devices, a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is strongly recommended because it combines neural signals with high-tech AAC devices [51].

Instead of muscle activity to support the functional communication, BCIs include the use of neural signals acquired by non-invasive (i.e., blinking) or invasive procedures (which can decode an identified signal and produce a functional message [52].

Leading to a remarkable improvement in QOL in those patients [48].

The system for communication can be divided in three groups according with their foundations as has been represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The image highlights three key aspects: Authenticity, trust, and verification in ensuring the accuracy and integrity of transmitted messages

Communication through blinking: When LIS patients communicate via blinking or other eye movements, they may convey their desires, thoughts, and personal needs [53].

This method of communication has multiple capacities and styles of AAC, including the use of transparent panels with numbers and/or letters mentioned before, eye movements, eye-tracking systems, eye-gaze sensing screens, and the ability to change switch positions to control different programs on devices [44].

In LIS patients, the ability to answer yes-no questions, choose elements on communication boards, and spell out words can be utilised by caregivers and/or devices for accurate communication through a system of eye movements/blinking supported by the remarkable adaptability and resilience of the LIS patients’ spirit to approach all frustrations and remarkable physical limitations [44].

Another effective method of communication for LIS cases is to use external switches combined with a Switch Interface (SI), where the SI receives input from the patient and delivers it to the AAC/program/computer/toy to elaborate on messages or trigger a desired action. Other authors have reported external switches attached to external devices, such as glasses, that can be activated by blinking [54].

Finally, the most sophisticated AAC (eye-gaze technology), such as eye-tracking systems, screen-based eye sensors, and modified external switches to control device use. However, eye-gaze programs require a person to select by systematically scanning different potential messages and icons and require the person’s blink when moving the eyes towards the target to provide a choice [54]. The last communication method is eye-tracking software integrated with speech-generating devices (Tobii Dynavox), which can provide individuals with an effective means of intercommunication [44].

A brain-computer interface provides an accurate way of communication through control signals generated by brain wave activity, enabling patients to command external devices and interact with their surroundings via a novel non-muscular channel [55].

The progressive advancement of BCI technologies has enabled LIS patients to better communicate with their environment and improve their QOL [15].

Brief comment on emerging non-invasive communication methods

Non-invasive BCIs provide healthcare caregivers with an effective means of communication with LIS patients. Brain-computer interfaces have supported LIS patients to move out of the prison.

Although its accuracy depends on responsiveness, the capacity of the patient to interact with medical equipment, and the individual’s condition, one of the novel noninvasive tools is the functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), which serves to monitor brain oxygenated haemoglobin levels (which indicate increased brain activity in the region) using near-infrared light for assessing brain cortical activity in LIS patients. This method identifies brain waves in specific brain areas associated with mental tasks, enabling patients to spell words or answer questions by activating corresponding neural circuits [56].

In conclusion, fNIRS is a promising way of intercommunication between the LIS patients and the device.

In the novel field of imagenology, functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated its advantages in LIS patients and has been the subject of research due to its capacity to detect alterations in blood flow, yielding remarkable insights into brain activity [48].

Mainly, when fMRI is used in conjunction with a BCI, it provides strong support for LIS communication by discerning a specific pattern of brain activity associated with several cognitive processes, empowering patients to express their desires and responses effectively as a communication tool to advance QOL [44].

Another emerging neuroimaging technique is Magnetoencephalography (MEG), which can record magnetic fields generated by cortical neuronal activity, providing precise localisation of the brain area engaged in cognitive processes and exceptional temporal resolution.

In LIS patients, MEG has demonstrated the capacity to detect communication desires and intention, capturing rapid neural dynamics signals via a method of the spatial distribution and timing, allowing investigators to specific of distinguish patterns related response or mental task [44] This procedure has some limitations such as increased sensitivity to noise/artifact movements and the need of controlled environments and specialized equipment.

However, MEG continues to be an advancing tool for better understanding of brain function in LIS patients and an extraordinary facilitator of a confident communication program.

When LIS patients are exposed to auditory or visual stimuli their brain cortex might generate a P300 event-related potential (waveform) in response to this stimulus leading the possibility to recognize a designated word or name which neuroimaging studies or EEG can monitor if the patient’s cognitive abilities remain adequately, functional attention is intact which circumvents a standard muscle control to respond to stimulations [57].

Brief comment on emerging invasive communication methods

Communication methods based on invasive BCI are typically characterised by electrodes implanted directly on the brain’s surface, capable of recording electrical activity and providing an exact, direct link between devices and neural signals from intention and cognition, supporting the distinction of different areas of brain cortex activation. Among this group, we have Electrocorticography (ECoG) based BCIs, which offer a novel hope for neuroimaging procedures with remarkable communication potential. However, this technique requires a surgical approach to the electrodes, which adds risks of infection, local complications, specific monitoring, and post-surgical management. On the other hand, analysing EcoG data properly is quite complex and requires advanced signal processing [44].

The success of electrocorticography point and click communication is related to noteworthy progress in BCIs, primarily for people with locked-in syndrome. This novel approach is due to its exceptional spatial and temporal resolution capabilities, which enable LIS patients to exert regulation over external devices through their brain waves appropriately, transporting their cognitive desires into actionable commands with the ability to engage in tasks (word composition), navigation of computer interfaces, or message creation, in the absence of motor activity [58].

Intracortical implantation of electrodes directly into the cerebral cortex via surgical approaches is also included in this group of invasive communication methods, enabling accurate recording of brain waves and providing a direct connection between cognition and external devices, allowing manipulation and communication of the surroundings [58].

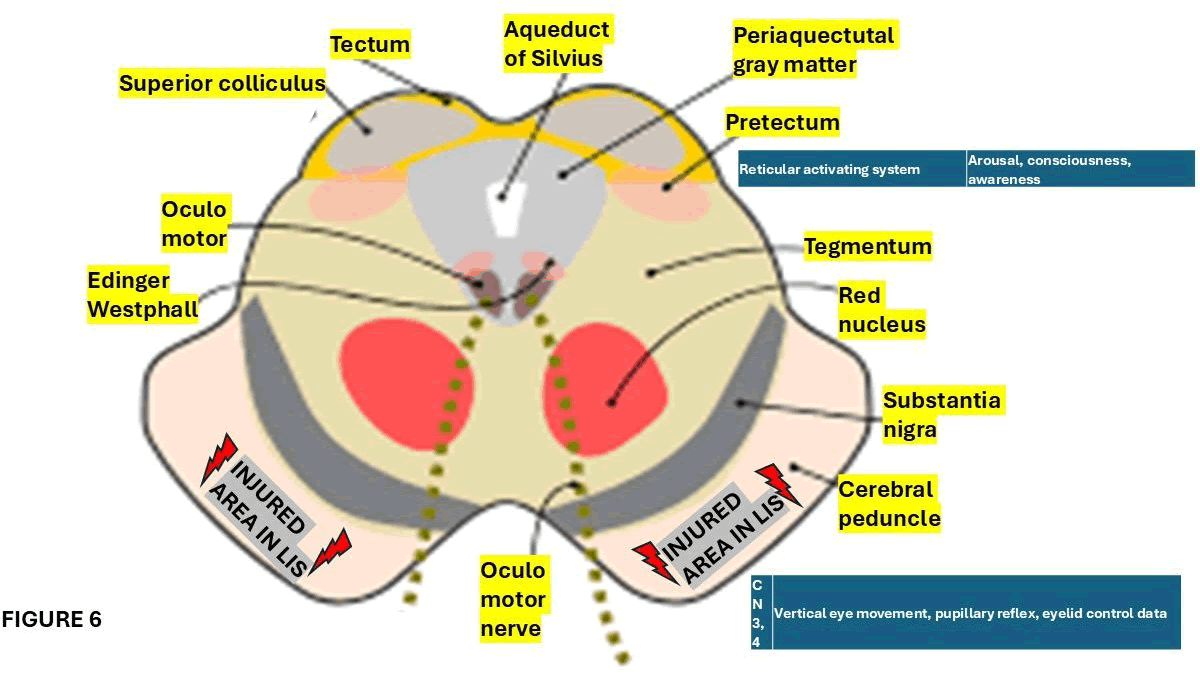

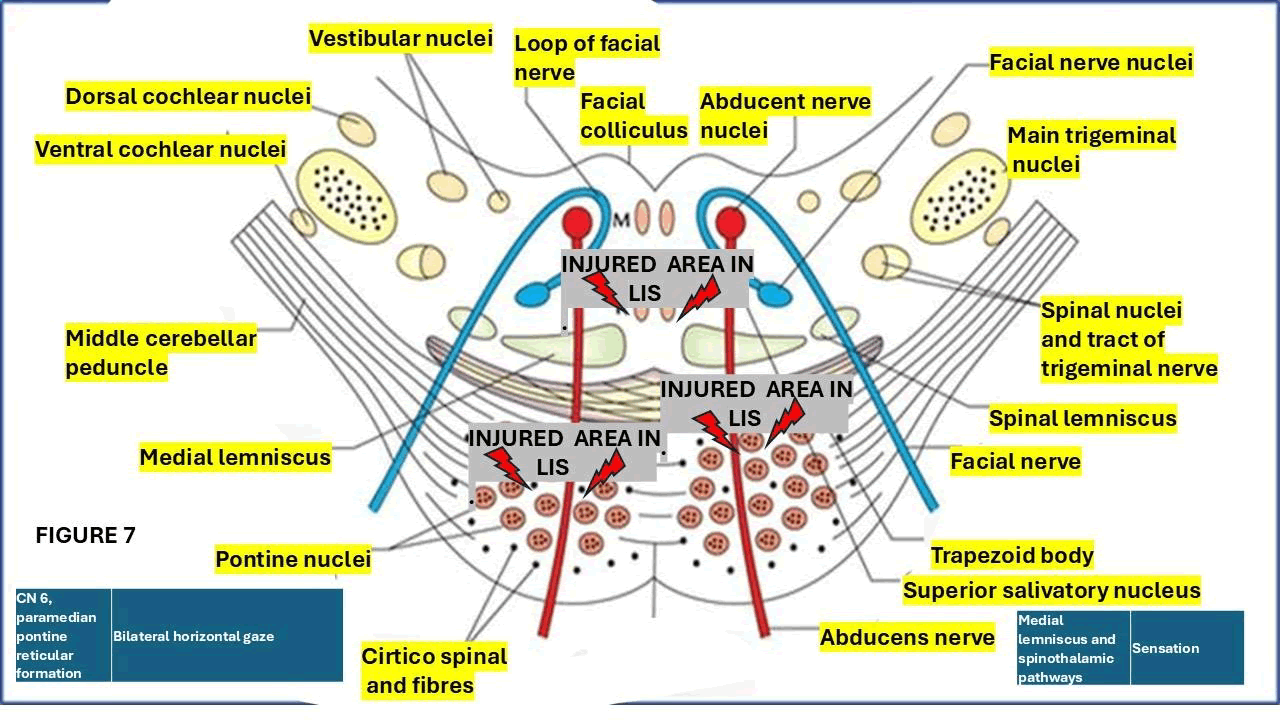

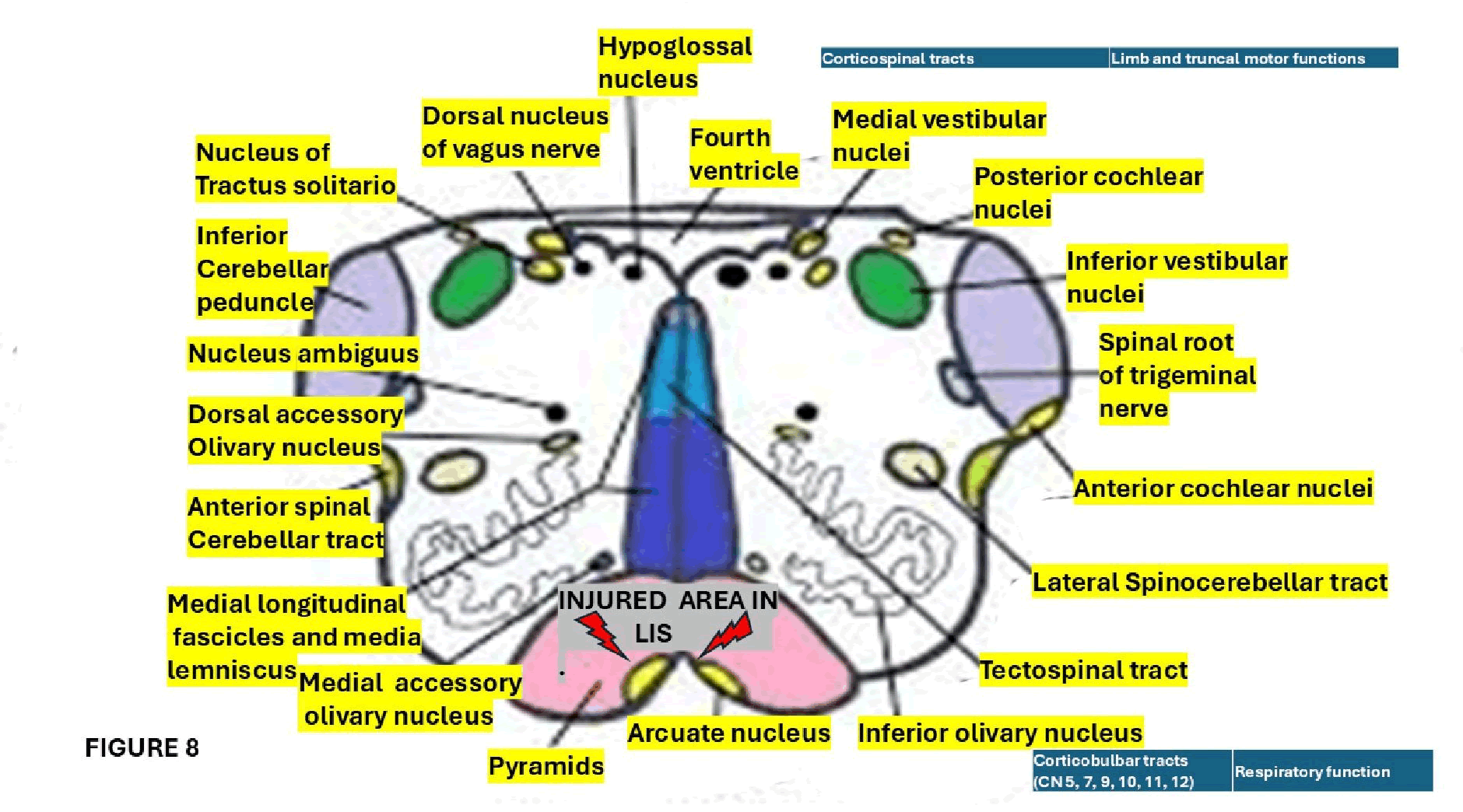

We hypothesized that the real achievement of the procedure implemented are closed related with the level of the lesion at the brainstem which can be identified by the clinical manifestations in LIS patients. The topographic diagnosis of the affected level of the brainstem is graphically represented in the Figures 6-8.

Figure 6: Shows a cross section of the midbrain at the level of superior colliculus, the site of the lesions and clinical manifestations

Figure 7: Represent a cross section of the pons showing the sites of the lesions and its clinical manifestations

Figure 8: Shows a cross section of the medulla oblongata, its main nucleus and tracts and the affected areas in LIS patients plus their clinical features

Conclusion

Final remarks on risks and benefits of BCIs

Nonâinvasive BCIs detect and interpret weak, variable neural signals, leading to potential inaccuracies in translating intention into action. Unfortunately, noninvasive BCIs require time for training and calibration, which requires patience, dedication, and cognitive and physical capabilities from LIS patients to achieve confident results.

On the other hand, invasive BCIs offer crucial advantages and significant risks for LIS cases, providing a strong link between devices and brain signals, offering heightened spatial and temporal precision, and highlighting the efficacy of decoding an individual’s intentions and thoughts.

As previously cited, surgical implantation of EcoG electrodes in the brain offers unparalleled spatial and temporal resolution. Still, it can be associated with medical risks that require meticulous postâoperative care.

In conclusion, the use of both methods in LIS cases provides groundbreaking benefits, including greater autonomy and improved communication. However, we did not find scientific evidence to support the administration of confident therapeutic drug to improve the LIS patient’s condition

Author Contributions

To thanks to Prof Thozama Dubula for his unconditional support.

Ethics Statement

This review does not require ethical approval.

Patient Privacy

All patientâidentifying information has been removed to ensure anonymity.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

Authors of this review report there is not conflicts of interest.

References

- A. Dumas, L. Sante, The count of Monte Cristo, Barnes & Noble Classics, (2004).

- J.B. Posner, C.B. Saper, N. Schiff, F. Plum, Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, (2008).

- N. Chisholm, G. Gillett, The patient’s journey: Living with locked-in syndrome, BMJ, 331(2005):94–97.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Sledz, M. Oddy, J.G. Beaumont, Psychological adjustment to locked-in syndrome, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 78(2007):1407–1408.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J-D. Bauby, The diving bell and the butterfly: A memoir of life in death, (1998).

- E. Farr, K. Altonji, R.L. Harvey, Locked-in syndrome: Practical rehabilitation management, PMR, 13(2021):1418–1428.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R.D. Adams, M. Victor, E.L. Mancall, Central pontine myelinolysis: A hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients, AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry, 81(1959):154-172.

- S. Sharma, S. Panda, S. Tiwari, A. Patel, V. Jain, Chronic encephalopathy and locked-in state due to scrub typhus related CNS vasculitis, J Neuroimmunol, 346(2020):577303.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.L. Hordila, C. GarcíaâBravo, D. PalaciosâCeña, J. PérezâCorrales, Lockedâin syndrome: A qualitative study of a life story, Brain Behav, 14(2024):e3495.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R.F. Kohnen, J.C.M. Lavrijsen, J.H.J. Bor, R.T.C.M. Koopmans, The prevalence and characteristics of patients with classic locked-in syndrome in Dutch nursing homes, J Neurol, 260(2013):1527–1534.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. Polhemus, D. Singh, A.A. Awad, S. Samuel, N.T. Chennu, et al. Lockedâin syndrome: A rare manifestation of neuropsychiatric lupus, Cureus, 16(2024):e62591.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S.J. Ankolekar, S. Parke, Case study: Pseudobulbar affect during recovery from locked-in syndrome, BJPsych Open, 10(2024):S272.

- J. Xia, R. Ahmed, Rapidly progressive lockedâin syndrome secondary to atypical herpes simplex virus-1 rhombencephalitis in an immunocompromised individual, IDCases, 37(2024):e02027.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E. Krim, A. Masri, E. Delmont, G. Le Masson, J. Boucraut, et al. Panâneurofascin autoimmune nodoparanodopathy: A case report and literature review, Medicine (Baltimore), 104(2025):e41304.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Rezvani, S.H. HosseiniâZahraei, A. Tootchi, C. Guger, Y. Chaibakhsh, et al. A review on the Performance of brainâcomputer interface systems used for patients with lockedâin and completely lockedâin syndrome, Cogn Neurodyn, 18(2023):1419–1443.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Vidal, Legal personhood and legal capacity: The case of the lockedâin syndrome, J Law Biosci, 12(2025):lsaf015.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.M. Das, K. Anosike, R.M.D. Asuncion, Locked-in syndrome, Statpearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL, USA, (2023).

- M.C. Rousseau, K. Baumstarck, M. Alessandrini, V. Blandin, T. Billette de Villemeur, et al. Quality of life in patients with locked-in syndrome: Evolution over a 6-year period, Orphanet J Rare Dis, 10(2015):88.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Li, Y. Yan, K. Kuehlmeyer, W. Huang, S. Laureys, et al. Clinical and ethical challenges in decision-making for patients with disorders of consciousness and locked-in syndrome from Chinese neurologists’ perspectives, Ther Adv Neurol Disord, 17(2024).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B. Vaithialingam, S. Gopal, D. Masapu, “Locked-in state” following anterior circulation aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, Indian J Crit Care Med, 27(2023):601–602.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. Finsterer, Transient lockedâin syndrome after aneurysmal subarachnoid bleeding due to spasm hypoxemia?, Indian J Crit Care Med, 28(2024):86.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- P. Heinz, B. Wolf, S. Schuldes, Lockedâin syndrome after pontine haemorrhage in an amphetamine abuser, Dtsch Arztebl Int, 121(2024):330.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S.P. Wrenn, J. Song, L. Billington, J.K. Czerwein, Lockedâin syndrome following elective cervical foraminotomy: A case report, Spinal Cord Ser Cases, 10(2024):32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.T. Barakat, S. Banerjee, T. Angelotti, Anaesthetic considerations for patients with lockedâin syndrome undergoing endoscopic procedures, Am J Case Rep, 25(2024):e942906â1–e942906â6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- V. Sinha, L. Lam, M.V. Nguyen, High doses of caffeineâinduced cerebral infarction leading to partial lockedâin syndrome in a young adult: A novel association?, Case Rep Neurol, 16(2024):115–121.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Chabert, C. Dauleac, M. BeaudoinâGobert, M. DeâQuelen, S. Ciancia, et al. Lockedâin syndrome after central pontine myelinolysis, An outstanding outcome of two patients, Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 11(2024):826–836.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- H.P. Dinkel, Recovery of locked-in syndrome in central pontine myelinolysis, Am J Case Rep, 14(2013):219-220.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- T.D. Singh, J.E. Fugate, A.A. Rabinstein, Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: A systematic review, Eur J Neurol, 21(2014):1443-1450.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R.H. Sterns, J.E. Riggs, S.S. Schochet, Osmotic demyelination syndrome following correction of hyponatremia, N Engl J Med, 314(1986):1535â1542.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.D. Norenberg, Central pontine myelinolysis: Historical and mechanistic considerations, Metab Brain Dis, 25(2010):97-106.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- G.C. DeLuca, Z. Nagy, M.M. Esirl, Evidence for a role for apoptosis in central pontine Myelinolysis, Acta Neuropathol, 103(2002):590-598.

- S. Kumar, M. Fowler, E. Gonzalez-Toledo, S.L. Jaffe, Central pontine myelinolysis, an update, Neurol Res, 28(2006):360-366.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B.K. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, A.M. Rojiani, C.M. Filley, Central and extrapontine myelinolysis: Then and now, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 65(2006):1-11.

- G.N. AlEssa, S.I. Alzahrani, A novel nonâinvasive EEGâSSVEP diagnostic tool for color vision deficiency in individuals with lockedâin syndrome, Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 12(2025):1498401.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- W.B. Thoreson, D.M. Dacey, Diverse cell types, circuits, and mechanisms for color vision in the vertebrate retina, Physiol Rev, 99(2019):1527–1573.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- N.B. Alamoudi, R.Z. AlShammari, R.S. AlOmar, N.A. AlShamlan, A.A. Alqahtani, et al. prevalence of color vision deficiency in medical students at a Saudi University, J Fam Community Med, 28(2021):196–201.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- V.A. Dohvoma, S.R. Ebana Mvogo, G. Kagmeni, N.R. Emini, E. Epee, et al. Color vision deficiency among biomedical students: A cross-sectional study, Clin Ophthalmol, 12(2018):1121–1124.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Zarazaga, J. Gutiérrez Vásquez, V. Pueyo Royo, Review of the main colour vision clinical assessment tests, Arch Soc Española Oftalmol, 94(2019):25–32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.S. Albahri, Z.T. Al-qaysi, L. Alzubaidi, A. Alnoor, O.S. Albahri, et al. A systematic review of using deep learning technology in the steady-state visually evoked potential-based brain-computer interface applications: Current trends and future trust methodology, Int J Telemedicine Appl, 2023:1–24.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Adama, M. Bogdan, Assessing consciousness in patients with lockedâin syndrome using their EEG, Front Neurosci, 19(2025):1604173.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Luo, Q. Rabbani, N.E. Crone, Brain-computer interface: Applications to speech decoding and synthesis to augment communication, Neurotherapeutics, 19(2022):263–273.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C. Libby, A. Wojahn, J.R. Nicolini, G. Gillette, Competency and capacity, (2023).

- C. Beale, J. LeeâDavey, T. Lee, A. Ruck Keene, M. F. Mirza, et al. Mental capacity in practice part 1: How do we really assess capacity?, BJPsych Advances, 2(2024):30.

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, General Comment No. 1 – Article 12: Equal Recognition Before the Law, (2014).

- K. Voity, T. Lopez, J.P. Chan, B.D. Greenwald, Update on how to approach a patient with locked-in syndrome and their communication ability, Brain Sci, 14(2024):92.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Z.R. Lugo, M.A. Bruno, O. Gosseries, A. Demertzi, L. Heine, et al. Beyond the gaze: Communicating in chronic locked-in syndrome, Brain Injury, 29(2015):1056.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.J. Jude, S. Haro, H. LeviâAharoni, H. Hashimoto, A.J. Acosta, et al. Decoding intended speech with an intracortical brainâcomputer interface in a person with longstanding Anarthria and lockedâin syndrome, bioRxiv, (2025).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M.J. Vansteensel, M.P. Branco, S. Leinders, Z.F. Freudenburg, A. Schippers, et al. Methodological recommendations for studies on the daily life implementation of implantable communicationâbrainâcomputer interfaces for individuals with lockedâin syndrome, Neurorehabil Neural Repair, 36(2022):666–677.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Elsahar, S. Hu, K. Bouazza-Marouf, D. Kerr, A. Mansor, Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) advances: A review of configurations for individuals with a speech disability, Sensors, 19(2019):1911.

- M. Ezzat, M. Maged, Y. Gamal, M. Adel, M. Alrahmawy, et al. Blink-to-live eye-based communication system for users with speech impairments, Sci Rep, 13(2023):7961.

- J.S. Brumberg, K.M. Pitt, A. Mantie-Kozlowski, J.D. Burnison, Brain–computer interfaces for augmentative and alternative communication: A tutorial, Am J Speech-Lang Pathol, 27(2018):1–12.

- S. Luo, Q. Rabbani, N.E. Crone, Brain-computer interface: Applications to speech decoding and synthesis to augment communication, Neurotherapeutics, 19(2022):263–273.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D.J. Kopsky, Y. Winninghoff, A.C.M. Winninghoff, J.M. Stolwijk-Swüste, A novel spelling system for locked-in syndrome patients using only eye contact, Disabil Rehabil, 36(2014):1723–1727.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S.W. Park, Y.L. Yim, S.H. Yi, H.Y. Kim, S.M. Jung, Augmentative and alternative communication training using eye blink switch for locked-in syndrome patient, Ann Rehabil Med, 36(2012):268–272.

- L.F. Nicolas-Alonso, J. Gomez-Gil, Brain computer interfaces, a review, Sensors, 12(2012):1211–1279.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L.K. Butler, S. Kiran, H. Tager-Flusberg, Functional near-infrared spectroscopy in the study of speech and language impairment across the life span: A systematic review, Am J Speech-Lang Pathol, 29(2020):1674–1701

- Z.R. Lugo, L.R. Quitadamo, L. Bianchi, F. Pellas, S. Veser, et al. Cognitive processing in non-communicative patients: What can event-related potentials tell us? Front Hum Neurosci, 10 (2016):569.

- D. Bacher, B. Jarosiewicz, N.Y. Masse, S.D. Stavisky, J.D. Simeral, et al. Neural point-and-click communication by a person with incomplete locked-in syndrome. Neurorehabilit Neural Repair, 29(2015):462–471.

Copyright: © 2025 Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.