Research Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2025) Volume 14, Issue 8

Posterior Reversible Encephalopathic Syndrome Related to Drug Therapy: Systematic Review

Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes1 and Humberto Foyaca Sibat2*2Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

Humberto Foyaca Sibat, Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa, Email: humbertofoyacasibat@gmail.com

Received: 04-Aug-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-168790; Editor assigned: 06-Aug-2025, Pre QC No. JDAR-25-168790 (PQ); Reviewed: 20-Aug-2025, QC No. JDAR-25-168790; Revised: 03-Sep-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-168790 (R); Published: 10-Sep-2025, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236461

Abstract

Introduction: Primarily affecting the posterior regions of the brain, a typically associated reversible white matter vasogenic oedema is the hallmark of the neurological condition known as Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES), characterized by altered cerebral autoregulation and endothelial dysfunction and the before mentioned reversible subcortical vasogenic oedema, leading to headaches, seizures, confusion, and visual disturbances. Whether PRES can be induced by drug therapy and what is the most common drug therapy applied is the main aid of this review.

Methods: We searched the medical literature, following the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement. From 01st, January 2006 to 31st, May 2025, the authors searched the scientific databases, Scopus, Embassy, Medline, and PubMed Central using the following searches: “Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome” OR “Therapy of PRESS” OR “ Aetiology of PRES” OR “Steroid therapy for PRES” OR “Management of PRES”, OR “Medical treatment of PRES”.

Results: After screening the full‐text articles for relevance, 61 articles were included for final review. However, no article was found when we searched for GS/NCC/responding to drug therapy.

Conclusions: The most frequent prescribed drug causing PRES is the steroid being also the medication of choice of treatment.

Keywords

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome; Steroid therapy; Therapy of PRES; Aetiology of PRES; Clinical features of PRES; Differential diagnosis

Introduction

Primarily affecting the posterior regions of the brain, a typically associated reversible white matter vasogenic oedema is the hallmark of the neurological condition known as Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES), characterized by altered cerebral autoregulation and endothelial dysfunction and the before mentioned reversible subcortical vasogenic oedema, leading to headaches, seizures, confusion, and visual disturbances. This syndrome was first time described by Hinchey and collaborators [1] F. rom all hospital admissions, the incidence of PRES has been calculated to be around 0.01%. Still, it may not accurately reflect the fundamental values due to the number of underreported cases resulting from a lack of recognition and variable clinical features.

Arterial hypertension and other factors affecting brain autoregulation are crucial in its development. Although PRES can involve persons of any age, it is more frequently seen, especially those patients between the ages of 20 and 50 years old. However, some children have also been reported. The comorbidity with various predisposing factors, including renal disease, autoimmune disorders, hypertension, eclampsia, and immunosuppressive therapies, among others, reflects the demographic distribution of PRES [2-5].

The demographic distribution of PRES confirms its comorbidities with various predisposing factors, including eclampsia, renal disease, hypertension, autoimmune disorders, and immunosuppressive therapies, among others [6].

Apart from the affected parietal-occipital lobes, other involved cerebral regions, including the cerebellum, frontal and temporal lobes, and brainstem, have been reported [7].

The main aim of this study is to answer the following research questions: How often is steroid therapy associated with PRES? What is the most likely pathogenesis of PRES from PCS disorders?

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

The PRISMA guidelines conducted this review. The databases searched included Scopus, Medline, and Embassy. The search strategy encompassed terms related to corticosteroids and PRES. Studies were selected if they were peer-reviewed publications examining corticosteroids in PRES, excluding non-English, non-Spanish, and non Portuguese publications, letters to the editor, editorials, and articles without appropriate primary endpoints. Data on demographics and clinical features, imaging findings, drug therapy regimes, and prognosis were extracted. To avoid the risk of bias, the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for case reports was used.

In this study, no attempt was made to identify individuals and no original patient data was collected from the literature review. The systematic review was conducted by the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

We systematically searched for a combination of terms, including “Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome”, “PRES”, “pathophysiology of PRES”, “treatment of PRES”, “management of PRES”, and medical subj ect headings and their relevant synonyms.

In this review, we selected observational studies and case reports or series. Exclusion criteria comprised articles written in different languages than English, Spanish, and Portuguese, letters to the editor, editorials, and studies that did not document the management of PRES. Two authors (Ibanez and Foyaca) independently screened the abstracts and titles of the records using Rayyan QCRI. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion among them. The selected full-text articles were then assessed based on the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles not published in a peer-reviewed j ournal, not published in English/Spanish/Portuguese language, or did not have the appropriate primary endpoint were removed. The extracted data included the year of publication, author’ s name, patient’ s clinical symptoms, sex, age, radiographic f indings, medical treatment, and outcomes.

Applying the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for case reports, the risk of bias in included case reports was assessed by two authors (Ibanez and Foyaca). This tool evaluates the clarity of the diagnosis, various dimensions of bias, the precision of the reported intervention, and the validity of the outcomes [8]. Descriptive statistics were implemented to summarize the findings.

From January 1, 2006, to January 31, 2025, we searched the databases Embase, Medline, Scopus, and PubMed Central using the search terms mentioned earlier. After removing duplicates, two reviewers (L DFIV and HFS) independently screened all titles and abstracts. They evaluated the full texts based on the inclusion criteria. Any disagreement between the reviewers involved in the literature search was resolved through discussion with all authors to reach a consensus.

Selection criteria

The following manuscripts were included in the systematic review:

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Inaccessibility to full text.

• Articles with unclear pathogenesis.

• Lack of relevant clinicopathological data.

• No-noriginal studies (i.e., editorials, letters, conference proceeding, book chapters).

• Anmi al model studies.

• Non-/Spanish/Portuguese/English studies as before mentioned.

The papers were thoroughly assessed, and duplicates were removed.

Data extraction and quality assessment

All selected data were tabulated in an electronic Excel database. That information included pathogenesis, drug management, initial clinical presentation, evaluation of PRES after treatment, follow-up, and status at the latest evaluation. The quality of the studies was categorized as good, poor, fair, or reasonable, in agreement with the National Institutes of Health criteria.

Quality and risk of bias

Using the JBI tool for case series and case reports, the risk of bias in all selected articles was assessed. This program served to evaluate several dimensions of bias, including the precision of the reported intervention, the clarity of diagnosis, and the validity of the reported results.

Of the 82 case reports and series selected for this review, most studies were found to have a low risk of bias. Specifically, 43 cases were rated as having a low risk of bias, 20 cases were found as having a moderate risk of bias, and 19 studies were rated as having a high risk of bias. The presence of studies with moderate and high risk of bias (despite many studies being rated as high quality) highlights the need for more standardized and comprehensive reporting in future research on PRES.

Statistical analysis

Without a comprehensive reference for the total number of PRES cases, the prevalence of PRES responding to drug therapy without side effect was searched through a comprehensive review. Statistical analyses were performed using XL STAT (add-on for Microsoft Excel, version 2021.4.1, Addinsoft SARL) and R-Studio. Variations in continuous variables were assessed using the Mann Whitney U-test. We presented descriptive statistics for continuous variables as median (95% Confidence Interval (95% CI)). All situations were evaluated using the Kaplan Meier method to identify relevant prognosticators. A model of multivariable Cox proportional hazards with a priori selection of covariates was used to check for independent prognostic effects.

Results and Discussion

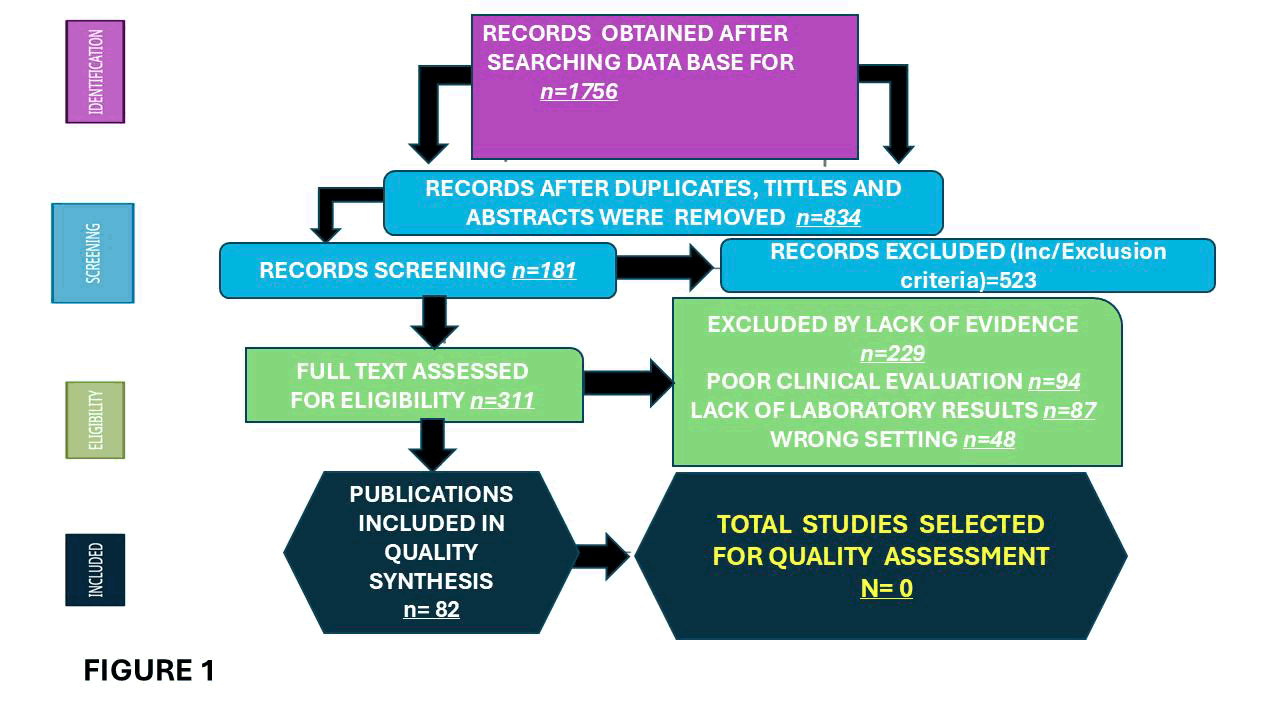

A total of 1756 titles were selected from the literature. After removing duplicates and excluding records. 834 relevant articles were examined. Three hundred eleven studies were unavailable for retrieval. After including six additional articles identified from citation searching, 229 were excluded for several reasons. A total of 82 records were identified from these searches. The resulting study titles were exported to Excel. We screened all remaining unique full-text articles, abstracts, and titles for eligibility. Articles relevant to PRES included the clinical presentation, investigations made, and treatment. The authors then screened these articles based on their abstracts. After further review, abstracts were excluded if they were irrelevant to the topic, outdated, or unavailable in Spanish, Portuguese, or English.

Series description and differences among groups

All the selected studies were relevant to the subj ect of this systematic review. None of the articles included were randomized controlled trials or prospective studies; all the articles were case reports and case series. Median age was 14.7 (range 4-84) with significant differences between age groups (p<0.001). We did not find remarkable variations in gender (p=0.064), although females presenting PRES were noticeably more frequent and slightly more prevalent.

Comments and final remarks

The pathophysiology of PRES includes an important malfunction of the Endothelial Cell (EC) and disruption of the cerebral autoregulation, leading to a vasogenic oedema [5,6]. A total 82 of PRES related to drug therapy were identified. Cases of PRES reportedly caused by steroids showed a mean age of approximately 21.4 years, with hypertension, headaches, seizures, and visual disturbances being common clinical sequelae. Typically, MRI findings confirmed vasogenic oedema in the bilateral parieto occipital lobes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Shows the flow diagram of selected articles following the PRISMA guidelines

Brief comments on drug therapy

From our systematic review, we determined that the most standard drug administered to treat PRES is corticosteroids, and we also found that steroids can be the cause of PRES in some people. The list of publications related to steroid causing PRES can be found in Table 1, and there, we also listed another therapeutic drug-causing PRES.

| Therapy | Ref. | Age | Sex | Clinical sequela | Management |

| Steroids | Kurahashi et al. [9], 2006 | 4 | F | Lethargic, convulsions, coma. Bronchial asthma | Intravenous hydrocortisone, continuous inhalation of b-2 stimulator, and additional oxygen; Sevoflurane; Furosemide; nicardipine, phenobarbital, and mannitol |

| Steroids | Irvin et al. [10], 2007 | 48 | F | Disoriented, agitated, autonomic instability, HTN | Trazodone and zolpidem, and a single dose of Haldol |

| Steroids | Fujitaet al. [11], 2008 | 23 | F | Fever, headache, fatigue, vomiting, tonic-clonic seizures | Diazepam, phenytoin, and nifedipine; Cyclophosphamide plasmapheresis; Thiopental; Betamethasone; Oral prednisolone; highdose; methylprednisolone |

| Steroids | Sinha and Hurley I [12], 2008 | 16 | F | Disorientation, motor apraxia, blurred vision, headache | Cyclophosphamide and high oral dose |

| Steroids | Nguyen et al. [13], 2009 | 32 | F | Nausea, seizures, dizziness, forgetfulness | Aprepitant, palonosetron, lorazepam, oral dexamethasone, rescue prochlorperazine, ondansetron, prochlorperazine, diphenhydramine, Dronabinol, diazepam, and fosphenytoin. |

| Steroids | Fukuyama et al. [14], 2011 | 6 | M | Generalized T/C seizures, drowsiness, cortical blindness | mPSL, BMT, methotrexate, FK506, magnesium, intravenous nicardipine, myeloid engraftment, mycophenolate mofetil, VPA |

| Steroids | Kumar and Rajam [15], 2011 | 6 | M | HTN, absence of visual fixation, seizures, cortical blindness, fever, macular rash | High dose oral prednisolone; second course of methylprednisolone; cyclosporine, etoposide and dexamethasone (HL H2004 protocol); ventilation |

| Steroids | Tsukamotoetof [16], 2012 | 28 | F | Generalized tonic-clonic convulsions with loss of consciousness | Nifedipine was used to control blood pressure and midazolam was used as an anticonvulsant consolidation therapy and intrathecal administration. Underwent BMT for ALL |

| Steroids | Kamezaki et al. [17], 2012 | 62 | F | High fever | Unspecified but rehabilitation was used |

| Steroids | Swarnalata et al. [18], 2012 | 11 | F | Generalized tonic clonic seizures | The patient was treated with antiepileptics and her dose was reduced to half of prednisolone |

| Steroids | Ozkok et al. [19], 2012 | 22 | F | HTN | 3 times week, hemodialysis and antihypertensive treatment with amlodipine and doxazosin |

| Steroids | Chennareddy et al. [20], 2013 | 17 | F | Case 1: Headache, blurry vision, and Generalized tonic-clonic seizures | Case 1: Analgesics and anticonvulsants |

| Steroids | Iinceciket al. [21], 2013 | 8 | M | Headache, confusion, seizures, HTN | Levetiracetam, pulse dose IVMP |

| Steroids | Chennareddy et al. [20],2013 | 16 | F | Case 2: Headache, blurred vision | Case N/A |

| Steroids | Alexander et al. [22], 2013 | 16 | M | Three episodes of tonic clonic seizures, tubulitis, and increased systolic blood pressure | The patient received five oral antihypertensive drugs. This included antiepileptic levetiracetam and minoxidil. The dose of tacrolimus was increased |

| Steroids | Gera et al. [23], 2014 | 5 | F | Headache, cortical blindness, seizure | For renal disease and renal failure, timely correction of fluid electrolyte was performed along with acid base balance. For hypertension, antihypertensives and nitroglycerin drips were administered IV albumin was administered for hypoalbuminemia. Lastly, HUS was treated using plasma exchanges and methylprednisolone medication dose adjustment |

| Steroids | Ding et al. [24], 2015 | 40 | M | HTN, headache, two episodes of generalized tonic-clonic seizures | Irbesartan and edaravone. A week later, he continued antihypertensive drugs with a tapering dose of methylprednisolone |

| Steroids | Camara- Lemarroy et al. [25], 2015 | 22 | F | Renal decline, severe bilateral occipital headache, seizures, confusion, hyperreflexia, reduced visual acuity | Hemodialysis, immunomodulation analgesic, IV diazepam (10 mg), IV nitroglycerin, IV phenytoin |

| Steroids Methyl cobala mine | Dar et al. [26], 2015 | 51 | F | Seizure, headache, HTN | Treatment with methylprednisolone and dexamethasone for one month |

| Steroids | Morrow et al. [27], 2015 | 53 | F | Insomnia, dizziness, general malaise, and a headache, holocephalic headache | High dose CR. 1250 mg oral prednisone. Hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine. Labetalol and amlodipine |

| Steroids | No author [28], 2016 | 33 | F | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | For seizures, anticonvulsants were administered. For SLE hydrocortisone along with mycophenolate mofetil. The patient was treated for pneumonia and underwent hemodialysis |

| Cyclophos phamide | Zekic et al. [29],2017 | 18 | F | The patient had fever, leg oedema, lupus nephritis, acute arthritis, and malaise | Antihypertensive, antiedema, and antiepileptic therapy |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 1:N/A; M Note: The mean age of all patients was 7 years | M | HTN; Note: Seizures and altered mental status were symptoms for >90% of the symptoms for >90% of cases although it was not specifically stated which cases had which symptoms | Levetiracetam, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient : N/A | M | N/A | Levetiracetam, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 5:N/A | F | HTN | Levetiracetam, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient N/A | M | HTN | Phenytoin, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 3:N/A | M | HTN | Methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient N/A | M | N/A | Levetiracetam |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 4:N/A | F | HTN | Levetiracetam, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 10:N/A | M | HTN | Methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 11:N/A | M | HTN | Levetiracetam, phenytoin, and methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 14:N/A | M | HTN | Phenytoin, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 15:N/A | M | HTN | Phenytoin |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 18:N/A | M | HTN | Phenytoin, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khan et al. [30], 2018 | Patient 19:N/A | F | HTN | Phenytoin, methotrexate |

| Steroids | Khanjar et al. [31], 2018 | Patient 1:34 | F | Tonic-clonic seizures, headache, decreased vision, HTN. All patients reported headaches and impaired vision | Management of blood pressure and seizures along with mechanical ventilation |

| Steroids | Khanjar et al. [31], 2018 | Patient 2:23 | F | Tonic-clonic seizures, HTN, and renal decline | Intubation, antihypertensives, antiepileptics, mechanical ventilation |

| Steroids | Khanjar et al. [31], 2018 | Patient 3:41 | F | N/A | Intubation, hemodialysis, antihypertensive, antiepileptic, mechanical ventilation |

| Steroids | Khanjar et al. [31] 2018 | Patient 4:29 | F | Seizures, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, hemophagocytic lymphocytosis | Rehab, mechanical ventilation |

| Steroids | Starcea et al. [32], 2018 | 10 | F | Seizures, respiratory distress, bilateral amaurosis, drooling, renal decline | Mechanical ventilation, blood transfusions, platelet concentrate, antibiotic therapy, continuous veno- venous hemofiltration, nifedipine, clonidine, dialysis |

| Steroids | Zhang et al. [33], 2018 | 22 | F | Sudden epileptic attacks, onset of seizures, HTN | Corticosteroid impulse therapy was not administered. Drugs were administered to decrease intracranial pressure, intravenous drugs to lower blood pressure, anmidazolam for sedation |

| Steroids | Kamo et al. [34], 2019 | 51 | F | Abducens palsy left eye, left-sided dysesthesia, dysarthria | Nicardipine with tranexamic acid and glycerol were administered Plasmapheresis |

| Steroids | Ulutas et al. [35], 2020 | 39 | M | Tonic clonic seizures, severe headaches, HTN | The patient was treated with antiedema therapy and antiepileptics. To control blood pressure, parenteral antihypertensive agents were administered |

| Steroids | Weeal [36], 2020 | 19 | M | Epilepticus, altered sensorium, HTN | For aspiration pneumonia, intravenous antibiotics and antiepileptics along with intermittent hemodialysis were administered |

| Steroids | Vernaza et al. [37], 2021 | 34 | F | Holocranial pulsatile cephalalgia with photophobia, headache, tonic- clonic seizure | Cyclosporine, IV artesunate, chloroquine and primaquine |

| Steroids | El Hage et al. [38], 2021 | 15 | M | Seizure, headache, HTN | Antihypertensives and antiepileptic medications |

| Steroids | Ismail et al. [39], 2021 | 57 | F | N/A | Levetiracetam and valproate |

| Steroids | Kitamura et al. [40], 2022 | 84 | F | Fatigue, mental status deteriorated, leg numbness | Rituximab, IV immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, hemodialysis, eculizumab, meningococcal vaccination, prednisolone was reduced |

| Steroids | Shibata et al. [41], 2022 | 51 | F | Headache, tonic-clonic seizures | Diazepam, phenytoin, levetiracetam, antihypertensive therapy |

| Steroids | Yang et al. [42], 2022 | Patient 1:48 | F | Sleepiness, diplopia | No treatment for PRES |

| Steroids | Yang et al. [42], 2022 | Patient 2:53 | F | Headache, giddiness | Unknown |

| Steroids | Yang et al. [42], 2022 | Patient 3:35 | F | Sleepiness, Visual impairment, delirium | Unknown |

| Steroids | Yang et al. [42], 2022 | Patient 4:48 | F | Epilepsy, visual impairment | Reduction/tapering of IVMP |

| Steroids | Yang et al. [42], 2022 | Patient 5:51 | F | Headache | Antihypertension and plasma exchange |

| Steroids | Mimura et al. [43], 2023 | 73 | F | Consciousness deteriorated | Intravenous methylprednisolone oral prednisolone; Rituximab; Intravenous administration of nicardipine and fluid removal by hemodialysis |

| Kumar et al. [64], 2023 | 59 | F | PRES after aortic valve replacement with concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting | Delayed diagnosis led to irreversible brain injury | |

| Parathyroid adenoma therapy | Ghosh et al. [65], 2023 | 60 | M | Recurrent acute pancreatitis caused by hypercalcemia | Parathyroid hormone concentrations, consistent with primary hyperparathyroidism |

| Two units of packed red cells transfusion | Kadam et al. [66], 2024 | 19 | F | Acute severe ulcerative colitis, atypical PRES | MX of severe anaemia and recurrent seizures, |

| Nebivolol | Astara et al. [67], 2024 | 33 | F | McCune-Albright Syndrome | Mx of two episodes of epileptic seizures and episodes of ocular upward deviation and transient facial palsy |

| Metronidazol | Stadsholt et al. [68], 2024 | 52 | F | Right-sided hypoacusis, right-sided facial hypoesthesia and left-sided deviation on the Unterberger step test. | Vestibular schwannoma surgery |

| Tacrolimus | Tanaka et al. [70], 2024 | 59 | F | Dermatomyositis | Complicated by interstitial pneumonia positive for anti- melanoma differentiation- associated gene 5 (MDA-5) antibody and PRES |

| Zdraljevid et al. [71], 2024 | 31 | F | Altered sensorium, headache, seizures, hypertension, and laboratory disorders | Hemolysis-elevated liver enzymes-low platelet counts | |

| Immunosup ressive therapy | Yang et al. [72], 2024 | 58 | M | End-stage cardiomyopathy | Two transplanted organs and died after super-refractory status epilepticus |

| No previous drug therapy | Ali et al. [73], 2024 | 45 | F | Poorly controlled hypertension and painless bilateral vision loss | Appropriate blood pressure management |

| Immunosup ressive therapy | Kakde et al. [74], 2025 | 22 | M | Acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | Despite aggressive drug therapy, the disorder progressed to multiorgan failure, and the patient died |

| Manickavasagam et al. [75], 2025 | 19 | M | Takayasu arteritis | Had significant control of hypertension and underwent aortorenal bypass | |

| Methadone | Ozgur et al. [76], 2025 | 62 | F | Bipolar disorder and Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy | Respiratory failure, necessitating intubation and management of these stress-related syndromes |

| Correction of hyponatremia | Handa et al. [77], 2025 | 31 | F | Unmasked acute intermittent porphyria and COVID-19 | Management of acute hepatic porphyria, severe hyponatremia, gastrointestinal disturbances neuropsychiatric symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 |

| Steroids and plasma exchange | Fujiwara et al. [78], 2025 | 28 | F | Singultus, nausea, difficulty eating, numbness on her neck and upper arms plus decrease in visual acuity in her left eye | Optic neuritis, area postrema syndrome, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and Sjogren' syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis |

| Undetermined | Sha al. [79], 2025 | 10 | F | Generalized swelling, dark- coloured urine, and two days of seizures following recent throat infection. | Treated symptomatically with levetiracetam for seizures and with furosemide and amlodipine for hypertension |

| Undetermined | Brezic et al. [80], 2025 | 35 | F | Post term pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia | Persistent vegetative state following a cardiac arrest after an elective cesarean delivery |

| Hypomag nesaemia | Rosatoal. [81], 2025 | 65 | F | Dysarthria ataxia, visual disturbances diarrhea, weakness of the lower limbs, dysdiadochokinesia and heel-knee dysmetria | Management of hypomagnesaemia |

| CSF outflow obstruction | Ogino et al. [82], 2025 | 47 | F | Acute Obstructive Hydrocephalus | Successfully treated with continuous ventricular drainage. hypertension control, sedation, and mechanical ventilation. Follow-up brain CT showed improvement of cerebral oedema and resolution of hydrocephalus. |

| Levantinib | Chen et al. [83], 2025 | 72 | F | Hepato-cellular carcinoma | After receiving lenvatinib therapy developed altered mental status, headaches, such as confusion, and severe hypertension secondary to PRES |

| Meropenem, vancomycin, and colistin | Salar et al. [84], 2025 | 8 | M | Celiac disease | Management of Vomiting, diarrhoea for two months, seizures, pallor, emaciation, drowsiness, generalized rash. tachycardic, hypertension, oxygen saturation of 65% Glasgow coma scale score of 10/15, hypertonia and hyperreflexia |

| Undertimed | Elshafeial [85], 2025 | 33 | F | Subarachnoid haemorrhage | Management of post-partum eclampsia. treatment plans that address patient-specific risk factors, including vascular dysfunction, are essential for managing presentations like PRES-associated SAH |

| Tx of eclampsia | Vennapausa et al. [86], 2025 | 33 | F | severe holocephalic headache, nausea and blurred vision | Severe arterial hypertension and neurology symptoms |

| Mx Primary Adrenal insufficiency | Srichawla et al. [87], 2025 | 59 | F | Mx of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arterial hypertension, coma, COVID-19, central variant of PRES | |

Mx of lung transplantation |

Kim et al [88], 2025 |

57%of 147 F/M |

|

Lung transplantation developed PREE |

Primary lung disease/ Connective tissue disease |

Table 1: Below, we provide some comments on the most relevant clinical features, age, gender, related drug, and the applied management for each case

Recently, Srichawla et al. [5] documented that corticosteroid therapy may induce PRES through subsequent increased cerebral blood flow, hypertension, and loss of autoregulation, and at the same time, may aid in the management of PRES, leading to improved blood brain barrier integrity, enhanced endothelial stability, and a provision of anti-inflammatory effects that may mitigate or reduce the formation of vasogenic oedema. Therefore, corticosteroid therapy may have a dual role in PRES by reducing inflammation and stabilizing the blood-brain barrier after treatment or potentially inducing the condition through arterial hypertension.

Drug therapy strategies classically included reduction or discontinuation of corticosteroid use, along with antiepileptic therapies and antihypertensive management. However, in some cases, other therapies, such as immunosuppression, haemodialysis, and supportive care for underlying conditions like renal failure or systemic lupus erythematosus, were necessary.

Medical treatment must include strong management of arterial hypertension and seizure control with antiepileptic drugs. To assess therapy response and detect potential complications, a close monitoring of vital signs, neurological status, and laboratory parameters must be performed. With appropriate drug therapy, cessation of the offending agent, and supportive measures, most cases will show resolution of imaging abnormalities over time and gradual improvement of clinical features [44].

The prognosis of PRES may be a complete resolution of the symptoms and partonomic signs on MRI studies after appropriate therapy.

However, in cases with delayed treatment initiation or concurrent severe systemic conditions, severe complications and mortality attributed to complications such as multiorgan failure and gastrointestinal haemorrhagic shock can be observed.

Due to its relatively sparse sympathetic innervation of the posterior circulation, arterial hypertension can overwhelm the autoregulatory capacity of brain vessels, leading to capillary leakage, hyper perfusion, and the formation of vasogenic oedema. This is most observed around the parieto-occipital cerebral lobes.

The exact pathophysiological mechanism of PRES remains unknown. However, we also hypothesized that endothelial dysfunction may disrupt the BBB integrity, leading to subsequent vasogenic oedema formation, which plays a central role in this syndrome, as reported by other authors [45]. However, the role played by pericytes in this mechanism has never been considered, and it is one of the most relevant hypotheses that we will present below in this study.

As we mentioned earlier, endothelial dysfunction plays a crucial role in the development of PRES. Several types of medical conditions, such as autoimmune diseases, renal failure, eclampsia, and immunosuppressive therapies, can inj ure endothelial cells, leading to subsequent oedema formation due to increased permeability [46].

Several times before, we have documented the role of proinflammatory mediators in the mechanism of blood brain barrier disruption caused by endothelial dysfunction in patients with neurocysticercosis, and we have presented some hypotheses to shed more light on the topic [47-55]. We hypothesized the role of cytokines and chemokines in the pathophysiology of PRES based on our previous studies and the findings reported by other investigations under different conditions [5].

Hypertension is a crucial factor in the development of PRES, as has been reported by other authors [56,57]

Arterial hypertension and associated water and sodium retention increase vascular sensitivity to catecholamines, altering renal function and exacerbating the brain hyper perfusion seen in PRES. It can overwhelm the the other hand, a met-aanalysis study conducted with eight randomized controlled trials reported no benefit of corticosteroids in the management of subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage [62] as we found in our review. We hypothesized that diminishing astrocyte activation and vascular growth, a technique used to temporarily open the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), which improves drug delivery to the brain, would be enhanced. The best procedure is Focused Ultrasound (FUS) combined with Microbubbles (MBs) trough ultrasound to induce cavitation (oscillations or bursting) of the microbubbles, which will create a localized disruption of the BBB, enabling drugs to penetrate to reduce inflammation-induced tissue damage, Sharma et al. reported a 23-year-old female patient presenting with PRES following Rituximab administration, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, in the context of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis [4]. Brief comments on differential diagnosis The differential diagnosis for PRES encompasses several neurological conditions that exhibit similar imaging features and clinical symptomatology, as outlined in Figure 2. autoregulatory properties of the cerebrum’s vasculature, leading to vasogenic oedema.

Intravenous infusion of nicardipine or clevidipine is the medication of choice to control hypertensive crises, which also has anti-spasmodic effects.

Brief comments on imaging findings

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) typically shows Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FL-AIR) sequences and symmetric hyperintensities on T2-weighted, representing the classic vasogenic oedema present in the affected subcortical white matter brain regions. In some patients presenting with the severe form of PRES, MRI can show Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) that may demonstrate restricted diffusion due to neuronal inj ury and cytotoxic oedema [58].

Corticosteroids have been used to treat brain vasogenic oedema for over six decades from bacterial meningitis and intracranial neoplasms [59,60]

Corticosteroids diminish the formation of cerebral oedema via inhibition of the Na ±, K ±, ATPase channel [61]. On the other hand, a met-aanalysis study conducted with eight randomized controlled trials reported no benefit of corticosteroids in the management of subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage [62] as we found in our review.

We hypothesized that diminishing astrocyte activation and vascular growth, a technique used to temporarily open the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), which improves drug delivery to the brain, would be enhanced. The best procedure is Focused Ultrasound (FUS) combined with Microbubbles (MBs) trough ultrasound to induce cavitation (oscillations or bursting) of the microbubbles, which will create a localized disruption of the BBB, enabling drugs to penetrate to reduce inflammation-induced tissue damage,

Sharma et al. reported a 23-year-old female patient presenting with PRES following Rituximab administration, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, in the context of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis [4].

Brief comments on differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for PRES encompasses several neurological conditions that exhibit similar imaging features and clinical symptomatology, as outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Show graphically the most relevant differential diagnosis of PRES

The clinical and radiological improvement to the drug therapy also serves to differentiate PRES from other disorders [63].

Brief comments on the cases reported recently

All cases reported in the medical literature related to drug therapy associated with PRES are listed in Table 1. Below, we provide some comments on the most relevant clinical features, age, gender, related drug, and the applied management for each case.

In 2023, Kumaar and colleagues reported a case of PRES that happened after aortic valve replacement with concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting, which is rarely reported as a cause for epileptic seizures following cardiac surgery. The authors documented that this is a reversible condition, but delayed diagnosis can lead to irreversible brain injury [64].

In 2023, Gosh and collaborators described a male patient from rural India who experienced concurrent manifestation of PRES and recurrent acute pancreatitis caused by remarkably elevated serum calcium levels and parathyroid hormone concentrations due to primary hyperparathyroidism. Therefore, in cases with the absence of autonomic dysfunction or acute arterial hypertension, a high suspicion of primary hyperparathyroidism as an underlying cause of PRES should be taken into consideration [65].

Kadam et al. described a 19-year-old female presenting acute severe ulcerative colitis, multiple seizure episodes and atypical PRES on an MRI brain, which has been rarely documented in the medical literature [66].

L ast year, Astara and collaborators reported a 33-year-old female with McCune-Albright Syndrome (MAS) and two episodes of epileptic seizures with two episodes of ocular upward deviation and transient facial palsy, each lasting a few minutes, followed by a postictal phase. No association between PRES and MAS, a rare genetic disorder characterized by fibrous dysplasia, has been published [67].

Stadsholt and colleagues reported a case presenting PRES with an associated vestibular schwannoma who developed a PRESS after being treated with metronidazole [68].

Narasimhan and Kumar [69] reported a series of seven retrospective cases with a primary oncological condition and diagnosed with PRES. The median age of patients in this study was 48 years.

No patient exhibited significantly elevated blood pressure during their inpatient stay. Altered consciousness with seizures was the primary initial manifestation in most patients, followed by headache. Their predominant observation on the MRI was T2 flair hyperintensity in the vertebra-basilar circulation. All cases attained nearly full neurological recovery by 28 days after steroid therapy. The 90-day all-cause mortality rate was 14% (one out of seven patients). There were no fatalities attributable to PRES. These authors concluded that we must extend our focus beyond conventional risk variables such as hypertension to consider additional clinical insults because delayed diagnosis may lead to poor neurological prognosis [69].

Tanaka et al. studied a 59-year-old woman presenting with a rash on the upper part of her hands and wrist j oint pain due to dermatomyositis complicated by interstitial pneumonia, positive for anti Melanoma Differentiation-Associated gene 5 (MD-5) antibody and PRES. This patient was initially treated with oral prednisolone and tacrolimus, and later, mycophenolate mofetil was administered, resulting in a favourable outcome [70].

Zdralj evic et al. investigated a previously healthy 31 year-old lady in the 38th week of pregnancy with arterial hypertension, Haemolysis-Elevated Liver Enzymes-Low Platelet counts (HELL P), and her MRI of the brain showed T2-weighted/FL AIR left-sided hyperintensity consistent with PRES. In total, 33 cases of HELL P associated with PRES have been reported in the literature. Nevertheless, PRES associated with HELL P syndrome is an extremely rare comorbidity of third-trimester/postpartum complications, which usually present with altered sensorium, headache, seizures, hypertension, and laboratory disorders [71].

Yang et al. reported a 58-year-old man with end-stage cardiomyopathy who presented an extended critical illness triggered by PRES in the immediate post-transplant period after a multiorgan transplant, leading to acute rejection of the two transplanted organs and died after a super- refractory status epilepticus [72].

L ast year, Ali et al. studied a 45-year-old female with uncontrolled arterial hypertension who presented with sudden, painless bilateral vision loss over half day duet to PRES confirmed by MRI of the brain. This report highlights a classic presentation of PRES in a middle-aged woman with poorly controlled arterial pressure, emphasizing the importance of appropriate blood pressure management and prompt recognition of this condition to prevent permanent neurological damage [73].

Recently, Kakde et al. reported a case of a 22-year-old male who presented with headache, vomiting, and right upper limb weakness, followed by generalized epileptic seizures and hypertensive crisis associated with PRES with microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, acute kidney injury, and markedly reduced ADAMTS13 activity a von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease, leading to haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, widespread microvascular thrombosis, and multiorgan dysfunction which caused a remarkable accumulation of ultra-large von Willebrand factor multimers and excessive platelet aggregation in the microcirculation leading to the diagnosis of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Despite aggressive drug therapy, the disorder progressed to multiorgan failure, and the patient died. This patient underscores the complex and fatal interplay between PRES and an acquired TTP, two rare but life-threatening conditions [65].

On the other hand, Manickavasagam et al. reported that a 19-year-old boy presented a Central variant of PRES and an associated Takayasu arteritis. The patient had significant control of hypertension and underwent an Aortorenal bypass, which avoided catastrophic complications, including death. Currently, he has reasonable control of hypertension, and he is on regular follow-up [74]. Most of the scientific community agreed that PRES is a rare complication of Takayasu arteritis [75].

Three months ago, Ozgur et al. [76] reported a 62-year old female with bipolar disorder and a history of opioid dependence on methadone 100 mg daily who experienced altered mental status, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and respiratory failure, necessitating intubation. They established that PRES and Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (TTC) and PRES are exceedingly rare but reversible complications associated with catecholamine surges during methadone withdrawal. Therefore, a swift identification and prompt management of these stress-related syndromes in patients undergoing methadone withdrawal is mandatory [76].

Handa et al. reported that a 31-year-old Vietnamese female initially presented with seizures, severe hyponatremia, and hypertension after COVID-19. She complained of recurrent epileptic seizures and developed PRES, as confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging. Further investigations revealed a genetic mutation of c.517 C>T iHn MBS, leading to a diagnosis of acute hepatic porphyria. Medical therapy with hemin remarkably improved her symptoms and corrected her electrolyte disturbance [77].

In January this year (2025), Fuj iwara and colleagues reported a 28-year-old woman’ s complaints of singultus, nausea, difficulty eating, numbness in her neck and upper arms, and a decrease in visual acuity in her left eye. MRI revealed optic neuritis and a lesion in the area postrema and was diagnosed as Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder (NMOSD) treated with corticosteroids and plasma exchange; later, she developed an established status epilepticus. A follow-up MRI revealed oedematous changes in the cortex and deep white matter of the parietal, occipital, and frontal lobes, as well as the basal ganglia and cerebellum, accompanied by meningeal enhancement and haemorrhage. Her serum test was positive for an anti aquaporin-4 antibody. In summary, these investigators presented a case of a young female who developed NMOSD in the clinical course of Sjögren’ s syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis and who then quickly developed PRES [78].

In March this year, Shah et al. reported a 10-10-year-old girl presenting stage 2 hypertension, generalized swelling, dark-coloured urine, two days of seizures following a recent throat infection, and a CT scan of the brain confirmed paediatric PRES [79].

Brezic and colleagues reported that a 35-year-old female presenting a persistent vegetative state following a cardiac arrest after an elective caesarean delivery for a post-term pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia and an MRI of the brain performed seven days after the cardiac arrest confirmed PRES [80].

Rosato and colleagues reported a case of a 65-year-old lady presenting dysarthria associated with ataxia, visual disturbances and diarrhoea, Weakness of the lower limbs, mild dysdiadochokinesia and mild heel-knee dysmetria, severe hypomagnesaemia and PRES was confirmed by MRI of the brain.

Therefore, hypomagnesaemia should be included as an uncommon and potentially reversible aetiology of PRES and must be considered for differential diagnosis [81].

Some authors presented a case of severe PRES complicated by obstructive hydrocephalus, and they documented that early diagnosis and appropriate therapy resulted in a favourable clinical outcome without neurological deficits [82].

Chen et al. reported a 72-year-old lady with a past medical history of hepatocellular carcinoma without a previous history of arterial hypertension who received lenvatinib therapy and developed symptoms of altered mental status and headaches, such as confusion and severe hypertension during treatment. Neuroimaging revealed characteristic f indings of PRES. Therefore, Lenvatinib- induced PRES is a less commonly recognized side effect [83].

In March this year, Salar et al. reported a 9-year-old child with a past medical history of dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac disease who developed a PRES. These investigators concluded that celiac disease can be a significant risk factor for PRES in children. They proposed that clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for PRES in children presenting celiac disease and associated arterial hypertension and neurological symptoms. They recommended that prompt recognition and management are vital to prevent severe complications and provide a good prognosis [84].

In January this year, Elshafei and his associate investigators reported a 33-year-old female complaining of acute severe headache, blurred vision and late postpartum eclampsia. Her MRI of the brain revealed an image suggestive of PRES with an acute Subarachnoid Haemorrhage (SAH). This reported case brings to light how eclampsia can be a risk factor for PRES, which can be haemorrhagic [85]. However, SAH remains an unusual but critical presentation [8].

Vennapausa et al. studied a 33-year-old Asian woman (Gravida 1, Para 1) presented with severe holocephalic headache, nausea and blurred vision two days after delivering her first baby via Caesarean Section (CS) under spinal anaesthesia presenting PRES in antepartum. She had severe arterial hypertension and neurological symptoms, and PRES was confirmed with neuroimaging. This report highlights the importance of early diagnosis and the diverse clinical presentations of PRES proper, as well as the role of therapy in facilitating a favourable outcome [86].

In February this year, Srichawla and collaborators reported a 59-year-old woman with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arterial hypertension, decreased level of consciousness Glasgow Coma Scale score of 7, previous COVID-19 infection, central variant of PRES, and primary adrenal insufficiency confirmed by a positive cosyntropin stimulation test and low AM cortisol levels. This report highlights primary adrenal insufficiency as a possible novel precipitant of the central variant of PRES [87],

A retrospective analysis of 147 cases that were approached by underwent lung transplantation between February 01, 2013, and December 31, 2023, was conducted by Kim et al., and they found that 7.5% of that group developed PRES and 45.5% vs. 18.4%, P=0.019, odds ratio=9.808; 95% CI, 1.064–90.38; P=0.044 were associated to connective tissue diseas-eassociated interstitial lung disease. Therefore, the presence of primary lung disease as preexisting connective tissue disease represents a significant risk factor for PRES following lung transplantation [88].

Based on the previous cases reported and case series, we concluded that drug therapy with steroids is the treatment of choice for PRES, but it is also the most standard drug able to cause PRES.

Conclusion

We afford some limitations for this systematic review that must be acknowledged. The main limitations were related to most of the data obtained from case reports and series, which may limit the generalizability of the findings and introduce bias. On the other hand, some patients may have been missed. Many publications did not report control groups. This issue presented a significant challenge in establishing causality.

We also found significant variability in the reporting of drug therapies, imaging, and clinical findings. Therefore, this heterogeneity complicates the drawing of definitive conclusions based on the synthesis of data. Underlying medical conditions and the concomitant use of multiple drug therapies were considered confounding variables, which interfered with the interpretation of the findings.

The presence of bias towards reporting cases with severe or unusual presentations, leading to an overrepresentation of specific drug therapy associations with PRES in the literature, affected our perception of the risk profile of drug-induced PRES and the true incidence.

We also note that the clinical features of the patients, underlying medical disorders, and drug therapies reported in the case report may not apply to all clinical settings. The variability of drug dosages, drug therapy protocols, and demographics surely influences the risk of PRES development. We believe that the duration of follow-up in most of the case reports was insufficient to capture the long-term outcomes fully and to get a proper idea about the prognosis of drug therapy-induced PRES.

We also considered that retrospective data collection or inadequate documentation may affect the reliability of the investigation findings due to the introduction of reporting bias.

Managing these limitations and conducting further research, we strongly recommend that forthcoming studies, such as prospective studies or larger case series, are essential for a better understanding of the pathophysiology, epidemiology, and management of drug therapy-induced PRES. These studies should address these limitations by designing the best studies and collecting comprehensive data. Nevertheless, to better elucidate the relationship between drug therapy and PRES, well-designed randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies are necessary. On the other hand, further investigation is essential into the pathophysiological mechanisms by which immunological mechanisms influence PRES development and lighter into the process of its resolution. A better understanding of these mechanisms at the molecular level could shed more light on the development of targeted drug therapies. Long-term follow-up investigations are necessary to determine the best practices for managing chronic sequela and avoid recurrence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Thozama Dubula, Head of Department on Internal Medicine and Therapeutic for his unconditional support in the management of this patient.

Author Contributions

Both investigators have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

The authors received no funds to perform the present research.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted using the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, the Italian and US privacy and sensitive data laws, and the internal regulations for retrospective studies of the Otolaryngology Section at Padova University and Brescia University.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained the informed consent from the case involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author will make the raw data supporting this article’s conclusions available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Thozama Dubula, Head of Department on Internal Medicine and Therapeutic for his unconditional support in the management of this patient.

References

- J. Hinchey, C. Chaves, B. Appignani, J. Breen, L. Pao, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, N Engl J Med, 334(1996):494–500.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B. Ansari, M. Saadatnia, Prevalence and risk factors of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in Isfahan, Iran, Adv Biomed Res, 10(2021):53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.D. Triplett, M.A. Kutlubaev, A.G. Kermode, T. Hardy, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): diagnosis and management, Pract Neurol, 22(2022):183–189.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- K. Sharma, S. Balachandar, M. Antony, V. Vikram, P. Duvooru, et al. Rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody) induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): A case report and literature review, Radiol Case Rep, 20(2024):1538–1547.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Srichawla, T. Kaur, H. Singh, Corticosteroids in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Friend or foe? A systematic review, World J Clin Cases, 13(2025):98768.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B. Ansari, M. Saadatnia, Prevalence and risk factors of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in Isfahan, Iran, Adv Biomed Res, 10(2021):53. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]2

- V. Gupta, V. Bhatia, N. Khandelwal, P. Singh, P. Singhi, Imaging findings in pediatric posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): 5 years of experience from a Tertiary Care Center in India, J Child Neurol, 31(2016):1166–1173.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- X. Zeng, Y. Zhang, J.S. Kwong, C. Zhang, S. Li, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review, J Evid Based Med, 8(2015):2–10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- H. Kurahashi, A. Okumura, T. Koide, Y. Ando, H. Hirata, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a child with bronchial asthma, Brain Dev, 28(2006):544–546.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- W. Irvin, G. MacDonald, J.K. Smith, W.Y. Kim, Dexamethasone-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, J Clin Oncol, 25(2007):2484–2486.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Fujita, K. Komatsu, S. Hatachi, M. Yagita, Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in a patient with Takayasu arteritis, Mod Rheumatol, 18(2008):623–629.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R. Sinha, R.M. Hurley, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in SLE nephritis, Postgrad Med J, 84(2008):56.

- M.T. Nguyen, I.Y. Virk, L. Chew, J.L. Villano, Extended use dexamethasone-associated posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, J Clin Neurosci, 16(2009):1688–1690.

- T. Fukuyama, M. Tanaka, Y. Nakazawa, N. Motoki, Y. Inaba, et al. Prophylactic treatment for hypertension and seizure in a case of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Pediatr Transplant, 15(2011):E169–E173.

- S. Kumar, L. Rajam, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES/RPLS) during pulse steroid therapy in macrophage activation syndrome, Indian J Pediatr, 78(2011):1002–1004.

- S. Tsukamoto, M. Takeuchi, C. Kawajiri, S. Tanaka, Y. Nagao, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in an adult patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after remission induction chemotherapy, Int J Hematol, 95(2012):204–208.

- M. Kamezaki, T. Kakimoto, T. Takeuchi, K. Akuta, H. Kasahara, et al. Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome of bilateral thalamus in acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Leuk Lymphoma, 53(2012):2083–2084.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- G. Swarnalatha, R. Ram, B.H. Pai, K.V. Dakshinamurty, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in minimal change disease, Indian J Nephrol, 22(2012):153–154.

- Ozkok, O.C. Elcioglu, A. Bakan, K.G. Atilgan, S. Alisir, A.R. Odabas, Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy in the course of Goodpasture syndrome, Ren Fail, 34(2012):254–256.

- S. Chennareddy, R. Adapa, B.K. Kishore, L. Rajasekhar, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus following methylprednisolone: report of two cases, Int J Rheum Dis, 16(2013):786–788.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Incecik, MÖ. Hergüner, D. Yildizdas, M. Yilmaz, G. Mert, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to pulse methylprednisolone therapy in a child, Turk J Pediatr, 55(2013):455–457.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. Alexander, V.G. David, S. Varughese, V. Tamilarasi, C.K. Jacob, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a renal allograft recipient: A complication of immunosuppression?, Indian J Nephrol, 23(2013):137–139.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D.N. Gera, S.B. Patil, A. Iyer, V.B. Kute, S. Gandhi, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in children with kidney disease, Indian J Nephrol, 24(2014):28–34.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Ding, K. Li, G. Li, X. Long, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome following paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a case report and literature review, Int J Clin Exp Med, 8(2015):11617–11620.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C.R. Camara-Lemarroy, M.A. Cruz-Moreno, R.N. Gamboa-Sarquis, K.A. Gonzalez-Padilla, H.E. Tamez-Perez, et al. Goodpasture syndrome and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, J Neurol Sci, 354(2015):135–137.

- A.M. Dar, M. Kumar, A.H. Malik, V. Saikia, K. Goel, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) associated with i.v Methyl prednisolone and Methylcobalamine, Ann Indian Acad Neurol, 18(2015):S44.

- S.A. Morrow, R. Rana, D. Lee, T. Paul, J.L. Mahon, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to high dose corticosteroids for an MS relapse, Case Rep Neurol Med, 2015(2015):325657.

- Abstracts of the 18th Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology Congress (APLAR), 26-29 September 2016, Shanghai, China, Int J Rheum Dis, 19(2016):3–293.

- T. Zekic, M.S. Benic, R.S. Antulov, I. Antoncic, S. Novak, The multifactorial origin of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in cyclophosphamide-treated lupus patients, Rheumatol Int, 37(2017):2105–2114.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S.J. Khan, A.A. Arshad, M.B. Fayyaz, I. Ud Din Mirza, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in pediatric cancer: Clinical and radiologic findings, J Glob Oncol, 4(2018):1–8.

- I. Khanjar, I. Abdulmomen, Y.M. Yahia, A.W. Al-Allaf, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in rheumatic autoimmune disease, Eur J Case Rep Intern Med, 5(2018):000866.

- M. Stârcea, C. Gavrilovici, M. Munteanu, I. Miron, Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, J Int Med Res, 46(2018):1172–1177.

- X.H. Zhang, X.R. Deng, F. Li, Y. Zhu, Z.L. Zhang, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report, Beijing Daxue Xuebao Yixueban, 50(2018):1102–1107.

- H. Kamo, Y. Ueno, M. Sugiyama, N. Miyamoto, K. Yamashiro, et al. Pontine hemorrhage accompanied by neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, J Neuroimmunol, 330(2019):19–22.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Ulutas, V. Çobankara, U. Karasu, N. Baser, I.H. Akbudak, A rare case with systemic lupus erythematosus manifested by two different neurologic entities; Guillain Barre syndrome and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Mediterr J Rheumatol, 31(2020):358–361.

- C.S. Wee, W.C. Yeoh, I.J., Low posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome–A rare complication after methylprednisolone, Bangla J Med, 31(2020):41-42.

- A. Vernaza, G. Pinilla-Monsalve, F. Cañas, Malaria and encephalopathy in a heart transplant recipient: A case report, Transpl Infect Dis, 23(2021):e13565.

- S. El Hage, D. Akiki, L. Khalife, E. Assaf, M.A. Jaoude, Rapid clinical recovery of PRES in IgA nephropathy and nephrotic syndrome post-renal transplant, Transpl Immunol, 68(2021):101450.

- F.S. Ismail, J. van de Nes, I. Kleffner, A broad spectrum of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome-a case series, BMC Neurol, 21(2021):386.

- F. Kitamura, M. Yamaguchi, M. Nishimura, ANCA-associated vasculitis with PRES treated with eculizumab: A case report, Mod Rheumatol Case Rep, 6(2022):254–259.

- T. Shibata, N. Hashimoto, M. Mase, Intracranial hemorrhage in PRES due to corticosteroid pulse therapy, Brain Disord, 7(2022):100040.

[Crossref]

- B. Yang, L. Guo, X. Yang, N. Yu, PRES after neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A case report and review, BMC Neurol, 22(2022):493.

- A. Mimura, K. Fujii, W. Sugi, PRES triggered by fluid retention and hypertension after steroid in ANCA vasculitis, Hypertens, 41(2023):e508.

- JD. Triplett, MA. Kutlubaev, AG. Kermode, T. Hardy, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): diagnosis and management, Pract Neurol, 22(2022):183–189. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- JE. Fugate, AA. Rabinstein, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions, Lancet Neurol, 14(2015):914–925.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- N. Shaikh, S. Nawaz, F. Ummunisa, A. Shahzad, J. Hussain, et al. Eclampsia and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): A retrospective review of risk factors and outcomes, Qatar Med J, (2021):4.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- H. Foyaca Sibat, L.F. Ibañez Valdés, Subarachnoid cysticercosis and ischemic stroke in epileptic patients, Seizures, InTechOpen, (2018).

- H. Foyaca Sibat, Neurocysticercosis, epilepsy, COVID-19 and a novel hypothesis: Case series and systematic review, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 15S(2021).

- H. Foyaca Sibat, Comorbidity of neurocysticercosis, HIV, cerebellar atrophy and SARS-CoV-2: Case report and systematic review, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 15S(2021).

- Valdés Lourdes Fátima, H. Foyaca Sibat, The role of oxidative stress in neurocysticercosis: A comprehensive research, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- Valdés Lourdes de Fátima, H. Foyaca Sibat, Ferropanoptosis in neurocysticercosis: A comprehensive research, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- M. Nico Garcia, I. Valdés Lourdes de Fátima, H. Foyaca-Sibat, Our hypotheses about the role of cuproferropanoptosis in neurocysticercosis and a comprehensive review, J Drug Alcohol Res, 12(2023): 9.

- Valdés Lourdes de Fátima, H. Foyaca Sibat, Novel hypotheses on the role of oligodendrocytes in neurocysticercosis: A comprehensive research, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023):17.

[Crossref]

- Valdés Lourdes de Fátima, H. Foyaca Sibat, New hypotheses on the role of microglias in ischemic reperfusion injury secondary to neurocysticercosis, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- L. de Fátima Ibañez Valdés, The role of rouget cells in neurocysticercosis, J Drug Alcohol Res, 13(2024):17.

- S. JZ, M. Young, Corticosteroids, heart failure, and hypertension: A role for immune cells? Endocrinology, 153(2012):5692–5700.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B.S. Srichawla, J. Quast, Magnesium deficiency: An overlooked key to the puzzle of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS)? J Neurol Sci, 453(2023):120796.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. K, Y. Yang, D. Guo, D. Sun, C. Li, Clinical and MRI features of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with atypical regions: A descriptive study with a large sample size, Front Neurol, 11(2020):194.

- N. Majd, P.R. Dasgupta, J.F. de Groot, Immunotherapy for Neuro-oncology, Adv Exp Med Biol, 1342 (2021):233–258.

- A.M. Cook, G. Morgan Jones, G.W.J. Hawryluk, Guidelines for the acute treatment of cerebral edema in neurocritical care patients, Neurocrit Care, 32:647–666, 2020.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.L. Betz, S.R. Ennis, G.P. Schielke, Blood-brain barrier sodium transport limits development of brain edema during partial ischemia in gerbils, Stroke, 20(1989):1253–1259.

- A.M. Cook, J.G. Morgan, G.W. Hawryluk, P. Mailloux, D. McLaughlin, et al. Guidelines for the Acute Treatment of Cerebral Edema in Neurocritical Care Patients, Neurocrit Care, 32(2020):647–666. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]60

- E.V. Hobson, I. Craven, S.C. Blank, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: A truly treatable neurologic illness, Perit Dial Int, 32(2012):590–594.

- R. Kumaar, L. Kapoor, G. Pramanick, P. Narayan, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: A rare cause of seizures following non-transplant cardiac surgery, Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 40(2023):377–380.

- R. Gosh, M. León-Ruiz, K. Bole, A novel adult case of recurrent acute Pancreatitis, Neurohospitalist, 14(2023):174–177.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Kadam, J. Kinkar, S.S. Toshniwal, S. Kumar, S. Naseri, Unraveling the rare association between ulcerative colitis and PRES: A case report, Cureus, 16(2024):e76617.

- K. Astara, C. Stenos, K. Kalafatakis, PRES in the context of McCune-Albright syndrome: A case report, Cureus, 16(2024):e76261.

- S. Stadsholt, A. Strauss, J. Kintzel. PRES following vestibular Schwannoma surgery–Case report and review, Brain Spine, 5(2024):104167.

- V.L. Narasimhan, P. Pavan Kumar, A pressing emergency in oncology: A case series, Cureus, 16(2024):e75028.

- K. Tanaka, Y. Kimura, A. Aoki, Successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, Intern Med, 64(2024):113–117.

- M. Zdraljevic, A. Pejovic, B. Jocic-Pivac, M. Budimkic, D.R. Jovanovic, et al. Rare association of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome–A case report and review of the literature, Heliyon, 10(2024):e40915.

- C.L. Yan, H. Hua, F. Ruiz, J. Margolesky, E.J. Bauerlein, et al. Fatal PRES and super-refractory status epilepticus after combined heart and kidney transplant: A case report and literature review, JHLT Open, 4(2024):100078.

- N.H. Ali, R.E. Alsulaiman, M.A. Abbas, F.A. Jamsheer, N. Alsudairy, Acute vision loss as the sole presenting symptom of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Cureus, 16(2024):e76042.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- P. Kakde, A. Andhele, A. Kadam, G. Bedi, S. Acharya, et al. Fatal interplay between acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: A case report, Radiol Case Rep, 20(2025):2995–2999.

- S. Manickavasagam, A. Viruthagiri, R.R. Rajendran, S. Murugan, Unveiling the link: Takayasu arteritis manifesting as posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, Radiol Case Rep, 20(2025):3314–3318.

- J. Jadib, S. Salam, H. Yassine, L. Chahidi El Ouazzani, L. Soussi O, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome revealing Takayasu’s arteritis in a child, Radiol Case Rep, (2021).

- S.S. Ozgur, Y. Shamoon, M.N. Al Rayess, S. Elkattawy, A. Ahmad, et al. A Case of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy and Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Following Methadone Withdrawal, Clin Case Rep, 13(2025):e70321.

- H. Handa, H. Masuda, S. Hanayama, A. Kajiyama, S. Suzuki, et al. Unmasked acute intermittent porphyria in a patient with COVIDÃ-associated posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, BMC Neurol, 25(2025):139.

- Y. Fujiwara, N. Mori, M. Fukuda, S. Tamaki, A. Furuta, A case of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder complicated by posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with pre-existing Sjögren's syndrome and autoimmune hepatitis, Cureus, 17(2025):e78098.

- B.K. Shah, S. Thakur, P.L. Uit, R. Gaire, Childhood posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in resource limited settings: Addressing diagnostic and therapeutic hurdles-a case report, Case Rep Pediatr, 27(2025): 9444554.

- N. Brezic, A. Sic, S. Gligorevic, Persistent vegetative state following a cardiac arrest in a patient with preeclampsia and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: A case report, Cureus, 17(2025):e78757.

- M.N. Rosato, M.L. Núñez Calvo, L. Barrera López, Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome related to severe hypomagnesaemia, Eur J Case Rep Intern Med, 12(2025):005098.

- R. Ogino, D. Yamamoto, S. Furuya, K. Teshigahara, J. Kamiyama, Acute obstructive hydrocephalus due to posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome successfully treated with continuous ventricular drainage: A case report, Cureus, 17(2025):e80803.

- M. Chen, J. Shen, R. Jia, M. Chang, J. Zhang, et al. Case report: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after lenvatinib treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, Front Pharmacol, 16(2025):1487009.

- H. Salar, K. Masroor Anns, M. Salar, F. Khan, M. Aman, et al. From gut to gray matter: A case report of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a pediatric patient with celiac disease, Clin Case Rep, 13(2025):e70260.

- M. Elshafei, H.A. Oweis, Y. Abdul Hafez, T. Alom, Z.M. Hayani, et al. Late postpartum eclampsia with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and subarachnoid haemorrhage: A case study, Medicina (Kaunas), 61(2025):77.

- J.R. Vennapusa, P.K. Godavarthy, S. Garikipaty, M. Kulkarni, S. Chippa, A (PRES)sing matter: Two cases of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in pregnancy and postpartum, Cureus, 17(2025):e79255.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B.S. Srichawla, V. Kipkorir, R. Lalla, Central-variant posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in association with adrenal insufficiency: A case report, Medicine (Baltimore), 104(2025):e41625.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- T.J. Kim, H.J. Lee, S. Park, S.-B. Ko, S.-H. Park, et al. Connective tissue disease is associated with the risk of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome following lung transplantation in Korea, Acute Crit Care, 40(2025):79-86.

[Crossref] ]Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Copyright: © 2025 Lourdes de Fátima Ibañez Valdés, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.