Review Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2022) Volume 11, Issue 11

Empowering Social Prescribing and Peer Support: A Proposed Therapeutic Alliance against Addiction and Substance Misuse within the Middle East

Richard Mottershead1* and Nafi Alonaizi22Department of Nursing, Military Medical Services, Saudi Arabia

Dr. Richard Mottershead, RAK College of Nursing, Ras Al Khaimah Medical & Health Sciences University, United Arab Emirates, Email: richard@rakmhsu.ac.ae

Received: 01-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JDAR-22-85239; Editor assigned: 03-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. JDAR-22-85239 (PQ); Reviewed: 17-Nov-2022, QC No. JDAR-22-85239; Revised: 22-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. JDAR-22-85239 (R); Published: 29-Nov-2022, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236208

Abstract

The authors propose that social prescribing is an empowering strategy to assist individuals to connect and thrive within their communities and supports improvements in their health and well-being. Whilst, social prescribing schemes have been developed within western healthcare systems for some decades and continue to gain popularity, there has been little evidence of its widespread use within the Middle East. This region has continued to be pre-dominantly focused on pharmaceutical interventions for individuals experiencing addiction and substance misuse and whilst it is acknowledged that there are enclaves throughout the region, these are not common practice.

A world shaped by a post-COVID-19 global economic crisis appears to have had detrimental effects on physical and mental health due to substance misuse and addictions. The use of social prescribing utilizes psychological and social factors rather than an overreliance on the bio-medical model which relies on biological interventions to treat addictions and substance use disorder. Firstly, the authors will advocate for a wider exploration of the use of social prescribing in order to create a holistic approach to combating the health and social care determinants of addictions and substance for the Middle Eastern region. The paper will demonstrate how the use of social prescribing could be used to reaffirm empowerment as a means of aiding people to become more independent of hospital institutions and current pharmaceutical interventions. Seminal work on empowerment and peer-support will be presented to create awareness on the challenges of establishing and promoting empowerment within entrenched bio-medical models of care. Secondly, the authors will remonstrate for a need to establish peer-support by empowering those with lived experiences of addictions and substance misuse issues to become members of the multi-disciplinary team to treat these conditions.

Keywords

Social prescribing; Psychosocial interventions; Addictions; Substance misuse; Peer-support; Middle east; Bio-medical model

Introduction

Individuals with addictions and substance use disorders are known to face a number of challenges and needs associated with social determinants of health including medical, social, emotional, financial, legal and housing. These challenges require innovative care pathways that create solutions, in addition to evidence based treatment for substance use problems [1]. As highlighted previously by the author Mottershead and Ghisoni 2021, psychosocial interventions are crucial in supporting the recovery of military veterans. Psychosocial interventions can also be adopted through social prescribing for effective management of addiction and related issues, and can be successfully used as independent treatment methods as well as adjuncts to pharmacological treatment plans [2].

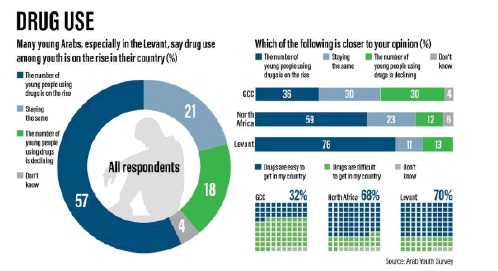

Substance abuse is a growing public health problem worldwide, including in the Arab countries. However, data describing substance abuse in Arab countries is still limited. This paper outlines the possible causes for the lack of substance related research in the Arab world. It also attempts to provide an overview of substance use in the Arab world to help the reader understand the magnitude of this public health problem and its negative consequences. By reading this article, the reader should know the prevalence of substance use among the general population, students, and patients in the Arab counties, identify the most commonly abused substances based on the available data, recognize the impact of substances in terms of morbidity and mortality, and identify the available prevention and treatment strategies. The authors include their suggestedrecommendations for Arab policymakers to control drug abuse. More research is still needed to help provide a clearer picture of the extent of drug abuse in the Arab world.

Substance Misuse within the Middle East

There appears to be an increase in the use of substance misuse within the Middle East in parallel to other countries within the western nations. With this comes a culture of reliance and overuse of alcohol and substance misuse with associated addiction, psychological, social and economic challenges associated with dependency. Within the Middle East, services and practices need to continue to develop and innovate to meet this emerging health and social care needs within a region that traditionally forbids the consumption of such substances. According to a 2017 report published within Lebanon’s Ministry of Health, there were 3,669 arrests for drug use in 2016, three times higher than in 2011 [3]. This report also indicated that within Levant individuals are consuming illegal substances at an increasingly young age, with the number of arrests of people under 18 more than tripling during the same time period.

Preliminary literature reviews indicate that despite judicial constraints, social, religious and cultural barriers on Muslims living within the region against the consumption of alcohol or substance misuse does exist and dependence is a growing problem. The aim of this paper is not to review the literature bur rather to present an evidence base strategy around social prescribing and peer support which can be used alongside pharmaceutical therapies. A systematic review of English and Arabic language literature was conducted by searching electronic databases (1975–2022) and conducting hand searches of Arab published journals. Studies investigating alcohol and/or substance use were reviewed to evidence the existing problems however, as stated the focus was on social prescribing and when applied to the Middle East there was minimal evidence of this as a widespread therapeutic strategy. The most commonly abused drugs within the region appear to be alcohol, heroin, and hashish. The literature review indicated that the research base was limited but confirmed that alcohol and substance abuse within the region. We strongly urge that further research into substance use and abuse in this region is prevalent but there is limited evidence of the expansion of therapies outside of mainstream bio-medical models. The need to migrate empowering alternative strategies is necessitated by the increase use of alcohol and substance misuse and how those with lived experiences can utilize peer-support to overcome the stigma and shame of these maladaptive behaviours.

Social prescribing and empowerment

The concept of empowerment is defined by Carabine (1996) and Masterson (2008) as a means of helping people to become more independent of others and institutions [4,5]. Carnes et. al., (2017) explains that since the 1990’s there has been a shift from the concept of biomedical healthcare models [6]. Instead, practitioners have focused on the dedevelopment of social prescribing which uses interventions focusing on the social component of care to support behavior change and address health inequalities by fostering social support networks. Mottershead (2022) explains that social prescribing can be an effective management strategy for the treatment of addiction and related issues, and can be successfully used as an independent treatment method as well as adjuncts to pharmacological treatment plans for those suffering with addiction and substance misuse issues [7].

This paper will argue that within the Middle East, there is associated stigma and shame linked with addictions and substance misuse. This is due to the religious and cultural norms and therefore individuals suffering from these conditions can be defined as a vulnerable group. This point is supported by Ali and Kelly (2004) who explain that a group can be identified as vulnerable by its association with social disempowerment [8]. This paper, seeks to addresses the gap within the research in that these individuals can be understood to be a vulnerable group on the basis that they are members of a stigmatised group within society [9]. Therefore, the author’s responsibility as healthcare professionals is to ensure that the wellbeing of these individuals and to empower their situation through a moral imperative approach as understood by Hillier, Mitchell, Mallett (2007) and Kant (1964) [10,11].

Masterson (2008), Burnard and Capman (2003) and the WHO (2010) indicate that within other institutional organisations within Health and Social Care there has been an expanding surge to adopt a model encompassing empowerment as it fosters a more adaptable and enabling model [5,12,13]. Social prescribing is a social movement that aims to create communities that are healthier. Dixon and Ornish (2021) explain that there is a growing recognition that the biomedical model of care is unable to solve exponential increase in health inequalities and physical and health problems [14]. Their research highlights the ability of social prescribing to treat a wider range of psychosocial ailments and not just of a biological nature. Burnard and Capman, (2003), Masterson, (2008), and WHO, (2010), highlight evidence that the concept of empowerment could create a more adaptable and enabling model for those making the recovery from addiction [5,12,13]. However, it is feasible that this concept may encounter some resistance from within the status quo of healthcare delivery systems as outlined by Barker over 20 years ago (1999) [15]. The authors suggested model is emancipatory in its suggestion of a shift from current practices. Oliver (1992) explains that emancipatory research is concerned with the generation of socially useful knowledge, within particular historical and social contexts [16]. The adoption of social prescribing and peer support for addictions and substance misuse issues would create a paradigm shift that came from the gradual rejection of the biomedical approach based on the pursuit of absolute knowledge through the scientific method. Oliver (1992) concludes that an emancipatory paradigm, as the name implies, relates to the facilitation of an approach with seeks to create the possibility to confront social needs at any level that it may occur [16].

The proposed exploration of a revised healthcare strategy demonstrates that the authors have sought to create a new discourse. Foucault (1972) suggests that discourse is more than just scientific research [17]; it is a collection of thoughts and ideas about practice that may include research but is not solely dependent upon it. He goes on to say that there “is no knowledge without a particular discursive practice and any discursive practice may be defined by the knowledge that it forms” (p18). Discursive practice therefore would suggest a discourse on empowerment and this paper seeks to support and disseminate what Foucault (1972) described as a new dominant reality via social prescribing and peer support [18].

Finfgeld’s model of empowerment for social prescribing and peer support

The authors have adapted Finfgeld’s model of empowerment (2004) to illustrate how current healthcare practitioners could work collaboratively towards a level of empowerment through the adopted social prescribing and peer-support [18]. Through the use of social prescribing individuals receiving care would be assigned a mentor via a peer support system. Consequently, this would allow for the development of an awareness of the key risk factors for the patient as the shared lived experiences of the mentor and patient would act as a safeguarding measure. Finfgeld (2004) identified that mutual respect was important in this alternative approach to empowerment [18], which involves learning from each other about knowledge and methods of coping. This research is derived from a focus on mental health nursing; it has far reaching potential (as illustrated within Figure 1, Model of Empowerment for Social Prescribing and Peer-Support) which can provide a useful insight into this paper’s focus. This approach has merits in removing some of the distance between the practitioners and those suffering from addiction and substance misuse and progress towards a more personal approach to managing. Previous work undertaken by Finfgeld (1999) has been explored and results extrapolated when related to an American Military context. Furthermore, it is believed that their later work can also hold purpose for this paper’s awareness on the theme of empowerment [19] (Table 1).

Figure 1: Drug usage and respondents of drugs.

| Antecedents | Barriers | Attributes | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of Identity | Stigma | Participation in Recovery | Positive |

|

Emerged New Identity | ||

| Loss of Power | Shame | Employment | |

| Self-Efficacy | Individuals’ Belief in Self | Choice | Strengthened Work Force |

| Confidence | Self-Esteem |  |

Positive Mental Well-being and Mental Health |

| Career Transition | Detached non-individualised re-entry | Support | Improved outcomes for Peer support |

| Loss of Prospects | Perceived low self-worth and no skills |  |

Undiminished National Pride |

| Belonging | Displaced | Moral Code | Family Cohesion |

| Power sharing relationship based on Mutuality | Organisational Resistance |  |

Negative |

| Family | Non-existence, dysfunction, presence of stigma and shame | Social, Economic and Institutional Adaptability | Feeling Inadequate |

| Frustration | |||

| Predisposition to Crime | Deviance identified as Crime by Society, Religion and the Judicial System | Crime | |

| Poor Mental-Well-being and Mental Health | |||

| Diminished outcomes for Peer support | |||

| Family breakdown |

Table 1: Model of Empowerment for Social Prescribing and Peer-Support

Finfgeld’s model (2004) also identifies barriers to empowerment, including the way that society is organised when managing this group and how systems embraces or resists empowerment. Therefore, the first point of contact the individual needing support for addiction and substance misuse has with the healthcare system is also an important factor. A point supported by Hall (2004), who warns that it is at this initial point of contact where organisational power is most evident due to its punitive nature [20]. In this case, punitive may appear be to a harsh term to use but there are associated barriers to receiving care for substance misuse and understanding from communities and families. National agendas within the Middle East such as Vision 2030 seek to support and accelerate nations ability to achieve targets (Vision 2030) [21]. Those suffering with addictions and substance misuse can still hold key skills that can eventually ensure a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and drive the ambitions of a nation based on effective governing. Agenda’s such as Vision 2030 has created the momentum needed to support empowerment and the realignment of traditional health models and services. There is a need to discuss this further in regards to what a paradigm shift might look like at the coal face of practice with this particular participant group. As this paper will evidence there is clear evidence from the research on peer support that it is the relationship and shared identity between the sub-groups that may well hold the catalyst for this paradigm shift within the region.

The friendly mentor: Peer support through shared lived experiences

Research undertaken by Mottershead (2019) indicated that there was evidence that if empowered by systems that could identify disenfranchised sub-groups, that a system of peer support could create positive outcomes in terms of therapeutic interaction [22].

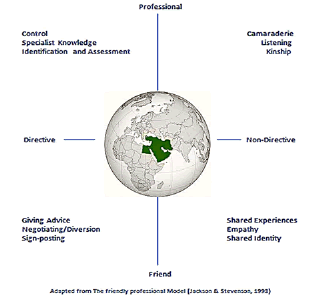

A proposed new model of social prescribing could see individuals with lived experiences of addictions and substance misuse (mentors) given an imperative to be empowered to support those suffering from these illnesses. Jackson and Stevenson (1998) highlight how a practitioner can be a friend and professional, with the ability to interchange and balance these two roles [23]. In addition, they stress that positive outcomes can be achieved if time is spent to talk, listen and discuss with the patient their needs. A model devised by Jackson and Stevenson (1998), has been adapted by the authors, can provide understanding into how four-dimensional roles can give insight into the need to be adaptable in terms of roles [23]. This paper suggests that if practitioners (mentors) adopt or develop the ability to role “toggle” then this can make processes such as formal identification of needs of the substance misuser and establishes that their management becomes an empowering practice. Figure 2, The Mentor and Peer Support highlights the aspects of the relationship and initiatives that should be identified when applying social prescribing via this therapeutic engagement.

Figure 2: The Mentor and Peer Support

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate that in relating to the concepts of Finfgeld (2004), Jackson and Stevenson (1998) [18,23], it is apparent that by empowering the shared identity it can become a powerful therapeutic agent to enable the patient undertaking recovery to take more control over their current situation. A previous study by Mottershead (2019) identified that a peer-support relationship could be a powerful cohesive bond that had clear supporting benefits if mentors felt that they were empowered to support those in their care [22]. In a later study Mottershead and Alonaizi (2021) demonstrated the potential of peer support within the Middle East, peer support with individuals with shared lived experiences [24]. Early research also showed the pitfalls that can be avoided as highlighted by Hummelvoll and Severinsson (2001) [25]. These researchers raise concern that unfortunately, within mental health services, a disempowering regime shaped by the organisation can result result in an often alien and oppressive environment that is not conducive to care. Through the use of the two adapted models of Jackson and Stevenson (1998) and Finfgeld (2004) [18,23], it is possible to theorise that the shared identity of ‘addict’ forms an empowering bond between the two sub-groups which transgresses the environment and inserts itself in wider community. Therefore, as the two adapted models have indicated, there is a potential empowering process within the relationship that both sub-groups have towards each other. However, it appears that to date most of the professional development around addictions within the Middle East have been focused upon traditional bio-medical models of care. Therefore, empowerment is inequitably linked to the concept of control, rather than the initial principle of empowerment as previously defined by Carabine (1996) and Masterson (2008) as a means of helping people to become more independent of others and institutions [4,5].

Locus of control for users of alcohol and substance misuse

Seligman’s theory of Locus of Control provides an insight into a key theme that emerged when the authors sought innovative practices to create holistic health and social care strategies [26,27]. The identification of control and its resonating importance around long-term recovery. Seligman’s Locus of Control theory can be said to apply to populations within the Middle East who despite religious [26], cultural, societal and judicial influences appear to struggle with the resilience to abstain. The authors believe that there is the possibility that if there was a sense of a lack of control and individuals did not feel empowered then this could result in substance misuse. Subsequently, this would lead to negative outcome ranging from unexpected employment challenges, strife, loss of identity (religious) to even crime and incarceration. This could lead to what Lewis and Urmston identity as “learned helplessness”. According, to Lewis and Urmston (2000) this concept explains that the process occurs in many situations when the individual has little control over their life then stress and burnout will become major concerns in daily functioning [28]. It is important to consider the notable role that self-image has in the development of delinquency and criminality, and advances helplessness as an explanatory concept.

It is apparent that there is a developing argument that the relationship between the mentor and substance abuser is where a crucial ‘checkpoint’ of power and empowerment lies. On this relationship, earlier research within community mental health nursing can be extrapolated to highlight the functions of empowerment as “relationships” that the peer support could employ [29].

Whilst the benefits of the two sub-group relationships is clear, there is still an unmistakable dilemma in that whilst the mentor may be of support to the addicts situation, there is the undeniable truth that the mentor also holds a power relationship in-line with their identity has having abstained and overcome the maladaptive lifestyle. Jack (1995) identifies an “oppressing/liberating” relationship as one that maintains the needs of the organisation whilst at least recognising the needs of the person who is accessing that organisation [29]. However, Hummelvoll and Severinsson (2001) noted that this phenomena, stipulated that the organisations aim is to empower or liberate the person who is seeking help and identifies the process as turnover, or throughput [25]. Whilst this may hold truth within the context of mental health nursing there is a challenge that it posed within the liberation element of the phenomena. The authors recommend a strategy that would see the addict having to adhere to the orders placed upon them and likewise the mentor must adhere to their responsibilities as outlined within their new professional codes of conduct. This relationship maintains the organisation by careful management of resources. However, as with the acknowledgement of previous systems within the UK and US, there are also examples of other systems which aim to divert the addict away from judicial incarceration.

The authors recommendation is for national strategies on peer-support and training needs to be provided to create an understanding that mentors may practice in this relationship in the belief that they are using empowerment strategies but unaware that this method of engagement creates great strain on the development of therapeutic relationships. Due in part to the constraints imposed by the reality of said ‘relationship’ existing within institutions. In parallel to research undertaken within the field of mental health nursing, it was noted that those undertaking peer-review experience their role as simply being agents of social control and managers [20]. This can be said to be reminiscent of the research of Gomm (1993) who identified the “disabling” relationship [30]. The authors believe that literature on peer-review holds evidence of this relationship by showing its power in the skills and knowledge of the mentors to aid their rehabilitation. Care must be taken for self-awareness as the management of the addict sub-group may also be used as a way of disabling or disempowering them by controlling their access to resources which may aid them. Therefore, by enforcing an empowering relationship, it is the esoteric knowledge of the mentor that causes a power imbalance within the supposed therapeutic relationship. It can therefore be surmised that mentors who believe that they are developing their knowledge in order to help the addict may actually be helping the organisation to manage and control this sub-group.

Alternatively, the authors believe that there could be evidence of another relationship between these two subgroups that of a “helping” relationship where the mentor intends to share knowledge as a way of empowering the person by allowing the addict to take control of their situation and life. The mentor may find that when managing the two identities, they must adopt a non-judgmental role, which may take less of precedence over the needs of the addict. This may cause conflict for the mentor when trying to balance between the needs of the addict and the needs of the institution. Again, this holds truth with the previous research of Finfgeld (2004) and can be illustrated within this paper’s adapted model [18].

Discussion

Conflict and empowerment: Lessons from psychiatric and mental health nursing

As advised by Carolan (2003), there is a need to adhere to reflexivity. This has led to the authors scrutinising “what I know and how I know it,” to recognise how we actively construct our knowledge” as advocated by Finlay (2002 p.532). It therefore became apparent that a solution for the treatment of addictions and substance abuse within the Middle East could be resolved by using a relationship suggested by Jack (1995) and derived from nursing theory. According to Herrick and Bartlett (2004), this relationship is known as the “brokerage” relationship and seeks to acquire services from identified and available resources on behalf of the person who needs them. The mentor acts as a care co-ordinator rather than just a care provider, which may cause professional conflict if healthcare providers are educated to a role in which they are identified as care experts. It is here that the use of the term therapy within nursing and may lack clarity and cause role confusion (Deacon 2003). When applying this concern raised by Deacon (2003), it is advisable to assume the adoption of the brokerage relationship. This relationship may be an important feature in preventing conflict when engaging with empowerment for the mentors and consequently the addicts. Within the description of the brokerage relationship by Jack (1995), it is possible to see a similarity to the helping relationship described earlier, but this later appears to be a conscious effort to share power within the relationship. As can be seen within a growing number of successful peer support and mentoring groups, the presence of the shared identity (former addict-addict) appears to be a key ingredient to success, as illustrated within Figure 1, Empowerment Features of Peer Support. The importance of further research on relationships and how they are seen to be professional and/ or empowering is an area that may illuminate additional insight into the roles and interactions between the sub-groups if the author’s recommendations are progressed.

This paper has explored the relationship that peer-support could encounter when they come into contact with institutions. It can be determined that success for the proposed strategy can be identified as a need to develop a form of knowledge on the new health and social care systems. The authors recommend that a national strategy on an empowering peer-support system would create a mutual relationship that requires a careful balance of personal and professional knowledge between the mentor and the addict.

Mottershead (2019) noted it was possible to treat psychological trauma through the use of peer support as subgroups with shared experience were more willing to share their feelings and concerns with a peer who had similar experiences and background. Shared identity was an empowering feature within that previous study due to enhanced trust, fairness and consistency. It has been evidenced by Mottershead and Alonaizi (2021) that trust was an integral building block to establishing credibility and assisting in forming therapeutic relationships as well as creating positive peer-to-peer engagement. This paper suggests adapted models attesting to the beneficial interaction between the two sub-groups which concurs with the findings by Eisen et al., (2012) [31]; Mottershead and Alonaizi (2021) who illustrates how peer support between sub-groups can provide a wide-range of benefits by creating an environment conducive to credibility. This credibility between the mentor and the addict could allow for an environment to be created that could foster empowerment through the use of the aforementioned “brokerage” relationship as the sub-groups seek to acquire services from available resources on behalf of those that need them. The suggested empowering peer-support system, shares trust due to the presence of credibility from the peer support available.

Critical social theory: Empowerment and the relationship between the sub-groups

In the review of the literature it became apparent that discourses on empowerment have been the subject of studies and exploration by many authors [28,32-34]. Collectively they suggest that Critical Social Theory provides insight into the exploration of empowerment and can be utilised to look at the oppressed and liberation of oppressed groups and individuals. These groups are those that have been identified as being powerless due to the lack of research and this could be said to be true on those suffering with addictions within the Middle East. The contentious acknowledgement of addicts numbers, and challenges in empowering peer-support schemes. An oppressed group as argued by Roberts (2000), is one that can identify with a dislike of self, but is unable to come together to oppose the view of others [35]. The mentors could establish initiatives under government support that Ryles (1999) would suggest understands the uses of power can lead to empowerment through changing working practices and the power within that practice [34].

Addicts within the region have existed within a total institution of the traditional hospital environment indicative of the bio-medical model [36]. Therefore, the authors believe that it stands to reason that for both sub-groups to become empowered there is a need for them to learn about the so cial policy directives, to identify resources that should be available to them, and ensure their own development of knowledge and information.

Research undertaken by Pieranunzi (1997), in accordance with a hermeneutical method on power and powerlessness, found that practitioners felt their power lay in the relationship they had with those they were responsible for [37]. Pieranunzi (1997) argues that it is impossible to use reductionist methods to identify individual empowering acts, as he describes power as being a dynamic relationship between two people. This holds truth would the proposed model as there is a significant presence of stigma and shame which may create difficulty for abusers to identify themselves and seek assistance from traditional healthcare systems. This paper suggests that those services utilizing mentors with lived experiences of addictions may be able to engage and influence the social institutions of which they now belong. This paper argues in line with the findings of Pieranunzi (1997) that the relationship between the two sub-groups is at its most empowering when this dynamic process of power balancing occurs between the mentor and the addict [37]. The authors suggest that a sense of “connectedness” between mentor and addict will facilitate this to happen, which was also influenced by the mentor’s knowledge of both the challenges associated with addiction. This knowledge could not be argued to be pure scientific knowledge, but a personal knowledge of the addict and their immediate needs. Pieranunzi (1997) argues that practitioners within psychiatry have this knowledge regardless of the environment that they find themselves and this would appear to be the case for the proposed model being recommended.

The authors suggest that in order to promote new empowering practices, there is a need to establish new ways of working with those suffering with addiction and this paper suggests that this paradigm shift could occur through an evolving schemata influenced by empowering practices. Research undertaken by Rumelhart (1980) and Mandler (1984) demonstrated a new understanding around the use of lived experiences which built upon the earlier work of Bartlett (1932) [38-40]. Through sharing and understanding the authors assert to expand understanding and create a new tacit knowledge around the topic addiction and substance misuse treatment within the Middle East. In adopting reflexivity through the course of this study the authors believe new tacit knowledge was derived from the authors’ identity (nurses) which generates new knowledge. Augier and Vendelo (2003) suggest that in order to promote growth within organisations, new forms of knowledge are developed by the codifying of existing knowledge and applying it to new situations such as the development of national strategies of social prescribing through peer support models [41,42].

Future Considerations and Conclusion

Einstein which was cited in Bowker, 2009, once remarked that behind all observable things lay something quite unknowable. The authors believe that within the recommendations of this paper there can be said to be a window into assumptions of the observable truths which are ‘dead ground’. This military phrase identifies a piece of land that is unobservable due to an obstruction of sight. Its existence is not in question, but as the realisation emerges that it creates an element of unknowing, it is subsequently subjected to the standard operating procedure, namely it is mined with ordnance, claymores are set as silent sentinels and barbed wire is used to prevent and deter movement. The paper seeks to create a new way of knowing through the establishment of a new dominant reality on a need to create expansive, holistic practices that encourage new support and aid to those suffering with addictions. Adapted empowerment based research models conducted by Finfgeld in 2004 and Jackson and Stevenson in 1998, demonstrate the shared identity as an empowering approach in order to manage the issue of addictions and substance misuses. The authors identify a need for further discussion and research to achieve an ontological view of approaches of empowerment. This paper offers an ability to reflect upon the proposed models and assumptions relating to them. Whilst the shared identity of the two sub-groups appears to be a source of strength, there appears to be an emerging need to detach and establish a new identity to those afflicted with the increasing issue of addictions within the Middle East. Critical social theory by Lewis and Urmston, as the authors would suggest would identify this group to be oppressed, either as an offending sub-group guilty through social, cultural, judicial and religious offences. The establishment of empowering and liberating peer-support schemes would allow these models to address the need for emancipatory practice and encourage further research for a marginalised group with complex healthcare needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Talaat Matar Tadross for his insight, kind review and suggestions. Dr. Matar is Professor of Psychiatry at RAK Medical & Health Sciences University and Consultant Psychiatrist at RAK Hospital, Ras Al Khaimah, UAE

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): Health responses to new psychoactive substances, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016

- R. Mottershead, M. Ghisoni, Horticultural therapy, nutrition and post-traumatic stress disorder in post-military veterans: Developing non-pharmaceutical interventions to complement existing therapeutic approaches, F1000Research, 10(2021):885

- S. Rose, Arab youth survey 2019: Drug use rising in Middle East party capital Lebanon, 2019

- J. Carabine, Critical Perspectives on Empowerment, Birmingham, Venture Press, 1996.

- S. Masterson, Mental health service user’s social and individual empowerment: Using theories of power to elucidate far-reaching strategies, J Ment Health, 15(2008):19-34.

- D. Carnes, R. Sohanpal, C. Frostick, S. Hull, R. Mathur, et al. The impact of a social prescribing service on patients in primary care: A mixed methods evaluation, BMC Health Serv Res, 17(2017):835.

- R. Mottershead, The social prescribing of psychosocial interventions in the treatment of addictions and substance use disorders with military veterans: A reclamation of identity and belonging, F1000Research, 11(2022):944.

- S. Ali, M. Kelly, Ethics and Social Research, Researching Society and Culture, 5(2004):115-127. [Crossref]

- E. Goffman, Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963.

- L. Hillier, A. Mitchell, S. Mallett, Duty of care: Researching with vulnerable people, Researching the Margins, 114-129

- I. Kant, Groundwork of the metaphysic of morals, 2020

- P. Burnard, C. Chapman, Professional and ethical issues in nursing, Balliere Tindall, London, 2003.

- World Health Organisation (2010) User empowerment in mental health: Empowerment is not a destination but a journey. WHO Regional office for Europe.

- M. Dixon, D. Ornish, Love in the time of COVID-19: Social prescribing and the paradox of isolation, Future Healthc J, 8(2021):53-56.

- P. Barker, The philosophy and practice of psychiatric nursing, London, Churchill Livingstone (1999).

- M. Oliver, Changing the social relations of research production, Disabil Soc, 7(1992):101-114.

- M. Foucault, The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language, New York, Barnes & Noble, 1972.

- D.L. Finfgeld, Empowerment of individuals with enduring mental health problems: Results from concept analyses and qualitative investigations, Adv Nurs Sci, 27(2004):44–52.

- D.L. Finfgeld, Courage as a process of pushing beyond the struggle, Qual Health Res, 9(1999):803–814.

- J.E. Hall, Restriction and control: The perceptions of mental health nurses in an acute inpatient setting, Issues Ment Health Nurs, 25(2004):539-552

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA): Saudi Vision; c2021, Saudi Vision 2030.

- R. Mottershead, British military veterans and the criminal justice system in the united kingdom: Situating the self in veteran research, University of Chester, 2019. [Crossref]

- S. Jackson, C. Stevenson, The gift of time from the friendly professional, Nurs Stand, 12(1998):31-33.

- R. Mottershead, N. Alonaizi, A narrative inquiry into the resettlement of armed forces personnel in the Arabian Gulf: A model for successful transition and positive mental well-being, F1000Res, 10(2021):1290.

- J.K. Hummelvoll, E.I. Severinsson, Imperative ideals and strenuous reality focusing on acute psychiatry, J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 8(2001):17-24.

- M.E.P. Seligman, Learned helplessness, Annu Rev Med, 23(1972):407–412.

- Z. Solomon, M. Mikulincer, Life events and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: The intervening role of locus of control and social support, Military Psychol, 2(1990):241-256.

- Lewis M, Urmston J, Flogging the dead horse: The myth of nursing empowerment?, J Nurs Manag, 8(2000):209–213.

- R. Jack, Empowerment in community care, London Chapman & Hall, 1995.

- R. Gomm, Health, welfare and practice: Reflecting on roles and relationships, London: Sage in association with The Open University, 1993.

- S.V. Eisen, M.R. Schultz, D. Vogt, M.E. Glickman, A. Elwy, et al. Mental and physical health status and alcohol and drug use following return from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan, Am J Public Health, 102(2012):S66-S73.

- S. Tilley, L. Pollock, L. Tait, (1999) Discourses on empowerment, J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 6(1999):53-60.

- L. Kuokkanen, H. Leino-Kilpi, Power and empowerment in nursing: Three theoretical approaches, J Adv Nurs, 31(2000):235-241.

- S.M. Ryles, A concept analysis of empowerment: Its relationship to mental health nursing, J Adv Nurs, 29(1999):600-607.

- S.M. Roberts, Development of a positive professional identity: Liberating oneself from the oppressor within, ANS Adv Nurs Sci, 22(2000):71-82.

- E. Goffman, Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates, London: Penguin Books, 1961.

- V.R. Pieranunzi, The lived experience of power and powerlessness in psychiatric nursing: A heideggerian analysis, Arch Psychiatr Nurs, 11(1997):155-162.

- D.E. Rumelhart, Schemata: the building blocks of cognition: Theoretical issues in reading comprehension, hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1980.

- J.M. Mandler, Stories, scripts, and scenes: Aspects of schema theory, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1984.

- F.C. Bartlett, Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- M. Augier, M.T. Vendelo, Networks, cognition and management of tacit knowledge, Paul Chapman Publishing, 6(2003):74-88

- K. Bowker, Albert einstein and meandering rivers fact book, Bluescope resources, 2009.

Copyright: © 2022 Richard Mottershead, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.