Research Article: Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research (2025) Volume 14, Issue 10

Cerebral Autosomic Dominant Arteriopathy With Sybcortical Infarct And Leukoencephalopathy (Cadasil). Novel Drug And Pericytes Implications

Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes1 and Humberto Foyaca Sibat2*2Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa

Humberto Foyaca Sibat, Department of Neurology, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Walter Sisulu University, South Africa, Email: humbertofoyacasibat@gmail.com

Received: 21-Jul-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-170249; Editor assigned: 23-Jul-2025, Pre QC No. JDAR-25-170249 (PQ); Reviewed: 06-Aug-2025, QC No. JDAR-25-170249; Revised: 18-Dec-2025, Manuscript No. JDAR-25-170249 (R); Published: 26-Dec-2025, DOI: 10.4303/JDAR/236474

Abstract

Introduction: Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is an extraordinary, inherited shape of cerebral Small Vessel Sickness (SVD), and is recognized as the most commonplace genetic SVD. This gene produces a transmembrane receptor specially present within the easy muscle cells of small arteries and the pericytes surrounding mind capillaries. variations in NOTCH3 can have an impact on clinical features together with the presence and kind of headache. These mutations usually alter the range of cysteine residues inside the receptor’s extracellular domain, leading to the buildup of granular osmiophilic material inside the partitions of small blood vessels in affected people. However, the real pathogenesis of this condition has not been well described up to date being it the main aid of this review plus to report novel therapeutic approaches.

Methods: We searched the medical literature, following the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement. From 01st, January 2010 to 31st, July 2025, the authors searched the scientific databases, Scopus, Embassy, Medline, and PubMed Central using the following searches: “CADASIL” OR “Pathogenesis of CADASIL” OR “Novel therapeutic approach for CADASIL” OR “Update information on CADASIL”, OR “CARASIL” OR “Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarct and leukoencephalopathy” OR “pericytes” OR “NOTCH3 mutations”.

Results: After screening the full‐text articles for relevance, 79 articles were included for final review. However, no article was found when we searched for or CADASIL responding to novel drug therapy.

Conclusions: The NOTCH3 signaling pathway performs a important function within the function of VSMCs and We hypothesize that modifications inside the NOTCH3 gene may want to compromise the stability and shape of blood vessel partitions disrupt preferred vascular structure and blood vessel characteristic, main to vascular accidents by way of protein deposits, that are traits of CADASIL. unfortunately, there’s no precise drug therapy or remedy for CADASIL. To our quality understanding, there are not any studies that correlate novel drug remedy methods and new hypotheses on pathogenesis pronounced up to date.

Keywords

Cadasil; Small-vessel disease; Pericytes; NOTCH3 mutations; CADASIL

Abbrevations

ANGPT1: Angiopoietin 1; APC: Antigen-Presenting Cell; AQP4: Aquaporin4; BBFR: Basal Blood Flow Resistance; BBB: Blood– Brain Barrier; BDNF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; BV: Blood Vessels; CA: Corpora Amylacea; CCL: Chemokine (C-C Motif) Ligand; CHAK: CC-Chemokine-Activated Killer; COX2: Cyclooxygenase-2; C/ EBP: CCAAT Enhancer Binding Protein; C1q: Complement C1q Chain A; C5ar1: Complement Component 5a Receptor 1; CD105: Endoglin; CD11b: alpha Chain of the Integrin Mac-1/CR3; CD13: Aminopep7dase N; CD163: Macrophage-Associated Antigen; CD4: T Cell Surface Glycoprotein CD4; CD45: Leukocyte-Common Antigen; CD68: Macrophage Antigen CD68; CMA: Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy; CV: Capillary Vessel; CX3CL1: C-X3-C Motif Chemokine; DAMP: Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns; EC: Endothelial Cell, EP: Epilepsy; EMTFs: Epithelial Tissue to Mesenchymal Transition Factors; ES: Epileptic Seizures; FK-β: Factor Kappa-β, FN: Fibronectin (Fn); FOXP3: Fork Head Boxp3; FS: Fibrotic Scar formation; FR: Flow Resistance; FSP: Fibroblast Secretory Protein; GLAST: Gamma-Ray Large Area Space Telescope; G-CSF: Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor; GS: Glymphatic System; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor; Groα/β/Γ: Growth-Regulated Protein Alpha/Beta/Gamma; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HMGB1: High Mobility Group Box 1; HPSCs: Human Pluripotent Stem Cells; I/R: Ischaemia-Reperfusion; ICAM-1: Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1; IDO1: Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1; IFN-Υ: Interferon Gamma; IL: Interleukin; ICAM-1: Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1; NFKb: Intranuclear Protein Complex Factor Kappa-B; Jag1: Jagged Canonical Notch Ligand 1; Ki-67: Kiel 67 Antigen; Lcfas: Free Long-Chain FaVy Acids; LFA-1: Lymphocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1; Lm: Laminin; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; Mac-1:Macrophage-1 Antigen; MMP: Matrix Metalloprotease; MIF: Macrophage Migration-Inhibitory Factor; MHC: Major Histocompatibility Complex; MCP-1: Monocyte ChemoaVractant Protein-1; MDSC: Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells; MIP-1α: Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-Alpha; MGluR: Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors; MLV: Meningeal Lymphatic Vessel; MMP2: Matrix Metallopeptidase 2; MSCs: Multipotent mesenchymal Stem Cells; Ngb: Neuroglobin; NOD1: Nucleotide Binding Oligomerization Domain Containing 1; NLRP13: NOD-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 13; Notch3: Notch Receptor 3; NOX4: NADPH Oxidase 4; NVU: Neurovascular Unit

Introduction

CADASIL tends to appear early, sometimes as early as a person’s twenties, and noticeable disease progression can occur within just a few years. Since it follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, only one copy of the mutated gene is sufficient to cause the disorder.

This disorder commonly presents in adulthood causing recurrent ischemic strokes, migraines headache with atypical aura before the age of menopause (20-40%) as the first symptom of the disease some decades before a stroke and even without aura with sharp pain, a throbbing pain, a dull ache or a tight band around the head (tension-type headache) plus cognitive decline, psychiatric symptoms, apathy, and mood disturbances. Symptoms often become progressively worse over time, leading to remarkable disability. Whilst CADASIL shows significant variations between and within patients, the important symptoms and signs include subcortical ischemic activities, psychiatric disturbances, migraine with air of mystery (MA), and cognitive decline. ailment development is quite exceptional among patients with CADASIL. whilst present, migraine with aura may be the first scientific manifestation. MA is a chance thing for cerebral thrombosis, maximum probable because of hypercoagulability, extended platelet aggregability, genetic predisposition, and hyper viscosity [1]. Diagnosis may involve a combination of family history, clinical assessment, neuroimaging (such as MRI), and skin biopsy to identify characteristic features in the small blood vessels. Now, there is no curative therapy for this condition. Therefore, the management On top of that, supportive management for emotional and cognitive symptoms should be applied. Forthcoming investigations are aimed at better understanding the pathophysiology of this pathological process and exploring potential therapeutic drug approaches for affected families [2].

Those findings suggest that one of a kind NOTCH3 mutations impact the variability in headache presentation visible in CADASIL, underscoring the significance of headache traits for each analysis and analysis on this situation. despite the fact that CADASIL is uncommon, with an estimated occurrence of 2 to five instances consistent with a 1,000 human beings, it remains the maximum common monogenic form of cerebral Small Vessel Disorder (cSVD). because of its clear genetic motive and well-defined pathology, CADASIL is frequently seemed as a “pure” form of cSVD and vascular dementia [2].

Additional research have proven that between 60% and 85% of people with CADASIL experience their first and subsequent lacunar strokes among the a long time of 45 and 50, frequently offering with lacunar syndromes [3,4].

Is centered on preventing headaches and strokes by way of controlling danger elements like high blood pressure and diabetes, amongst others.

The Notch signaling pathway turns on its target genes through a series of approaches, which include protein change, translocation, publish-translational adjustments, and ligand-mediated activation. as soon as the Notch receptor is synthesized, it undergoes proteolytic cleavage at website 1 (S1) with the aid of a Furin-like convertase within the golgi equipment. Following this transformation, the receptor is transported to the cell surface inside the form of a heterodimer, stabilized by way of noncovalent bonds. This interplay reasons a structural shift within the receptor that exhibits web page 2 (S2), allowing cleavage by way of a metalloprotease [5].

Numerous pathogenic mechanisms are connected to mutant NOTCH3 [6]. One such mechanism involves the neighborhood buildup of the NOTCH3 extracellular domain in vascular easy muscle cells because of impaired endocytosis and aggregation. This accumulation blocks protein degradation and ubiquitination, contributing to the formation of Granular Osmiophilic Material (GOM) [7].

Despite these mutations, the affinity of mutant receptors for ligand binding generally remains unchanged, though in some cases, signaling activity may actually be heightened [8,9].

From 2017 to 2023, Szymanowicz et al. A study involving 53 individuals diagnosed with CADASIL aimed to explore the relationship between specific NOTCH3 gene variants and their associated clinical manifestations. Genetic testing centered on exons 3, 4, 5, 11, and 12 of the NOTCH3 gene, as most of the people of pathogenic mutations in CADASIL are located inside exons 2 to 24, which code for the epidermal boom issue (EGF)-like domain names of the NOTCH3 protein. on account that exon 4 is the most commonplace website online for mutations, it’s miles advocated because the place to begin for genetic screening, followed by means of analysis of additional exons if vital.

The researchers identified six different NOTCH3 variants. Among them, three mutations—p.Cys144Arg, p.Tyr189Cys, and p.Arg153Cys—were considered pathogenic, while two—p.Ala202 and p.Thr101—were deemed benign. This study was the first to describe clinical symptoms, including headache, associated with this specific genetic change [10].

Further research has indicated that other may also play a role in the disease process, offering new insight into CADASIL pathophysiology and paving the way for potential therapeutic developments [11,12].

The abnormal accumulation of the extracellular domain (NOTCH3ECD) at the surface of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) and pericytes has been suggested to be caused by misfolding of the mutant NOTCH3 protein. A hallmark of CADASIL pathology is the presence of Granular Osmiophilic Material (GOM) deposits near or within the walls of deteriorating small blood vessels [13].

Various extracellular matrix components, such as oligomerized NOTCH3 Extracellular Domain (NOTCH3ECD), Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and other proteins like vitronectin, Serum Amyloid P Component (SAP), endostatin, and Latent Transforming Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 (LTBP 1) were found to make up Granular Osmiophilic Material (GOM) (Panahi). Other studies have shown that SAP is co-localized with NOTCH3ECD in GOM, suggesting an amyloid-like pattern of deposition. Despite this finding, the precise role of SAP, as well as the pathogenic significance of GOM deposits in CADASIL, remains uncertain and continues to be explored [14,15].

While dysregulation of the Transforming Growth Factorbeta (TGF-β) signaling pathway has been proposed as a potential mechanism contributing to CADASIL since 2014 [14], environmental influences such as high blood pressure and tobacco use may also affect the severity and presentation of the disease [16].

The primary objective of this review is to identify published research that explores the relationship between emerging therapeutic strategies and the underlying disease mechanisms in CADASIL, as well as to present new perspectives and hypotheses on these topics.

Materials and Methods

We searched the medical literature, following the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement. From 01st, January 2010 to 31st, July 2025, the authors searched the scientific databases, Scopus, Embassy, Medline, and PubMed Central using the following searches: “CADASIL” OR “Pathogenesis of CADASIL” OR “Novel therapeutic approach for CADASIL” OR “Update information on CADASIL”, OR “CARASIL” OR “Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarct and leukoencephalopathy” OR “pericytes” OR “NOTCH3 mutations.” All databases were searched using filters “past 10 years” and controlled trials only, yielding 45 records from Scopus, Embassy and 34 from PubMed and Google Scholar. Records from all databases were combined, and all duplicates were removed, resulting in a total of 14 unique results. Of those 14 results, each article was individually screened for eligibility. A total of 14 records were excluded because they did not measure declarative memory, and they did not correlate novel therapeutic approach and pathogenesis in a large series.

Search strategy

The PRISMA guidelines conducted this review. The databases searched included Scopus, Medline, and Embase. The search strategy encompassed terms related to Sth and NCC. Studies were selected if they were peer-reviewed publications referring to CADASIL, excluding non-English, non-Spanish, and non-Portuguese publications, letters to the editor, editorials, and articles without appropriate primary endpoints. Data on demographics and clinical features, imaging findings, drug therapy regimes, and prognosis were extracted. To minimise the risk of bias, the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for case reports was utilised.

In this study, no attempt was made to identify individuals and no original patient data were collected from the literature review. The systematic review is conducted by the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Discrepancies among the authors were resolved through scientific analysis and discussion

The full-text manuscripts selected for analysis were then assessed based on the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The extracted data included the year of publication, the author’s name, the patient’s clinical symptoms, sex, age, CT scan and MRI findings, drug therapy, and outcomes.

Applying the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for case reports, the risk of bias in included case reports was assessed by two authors (Ibanez and Foyaca). This tool evaluates the clarity of the diagnosis, various dimensions of bias, the precision of the reported intervention, and the validity of the outcomes [8]. Descriptive statistics were implemented to summarise the findings.

Selection criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Inaccessibility to full text. • Articles with unclear description of CADASIL, NOTCH3 mutation, medical approaches, pathogenesis.

• Lack of relevant clinical data.

• Non-original studies (i.e., editorials, letters, conference proceeding, book chapters).

• Non-/Spanish/Portuguese/English studies as before mentioned.

Data extraction and quality assessment

All selected data were tabulated in an electronic Excel database. That information included pathogenesis, drug therapy, initial clinical presentation, evaluation of CADASIL after treatment, follow-up, and status at the latest evaluation. The quality of the studies was categorized as good, poor, fair, or reasonable, in agreement with the National Institutes of Health criteria.

Quality and risk of bias

Using the JBI tool for case series and case reports, the risk of bias in all selected articles was assessed. This program served to evaluate several dimensions of bias, including the precision of the reported intervention, the clarity of diagnosis, and the validity of the reported results.

Of the 293 case reports and series selected for this review, most studies were found to have a low risk of bias. Specifically, nine publications were rated as having a high risk of bias. The presence of studies with moderate and high risk of bias (despite many studies being rated as high quality) highlights the need for more standardized and comprehensive reporting in future research.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT (add-on for Microsoft Excel, version 2021.4.1, Addinsoft SARL) and RStudio (version 4.3.1, https://www.rstudio.com/).

Variations in continuous variables were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. We presented descriptive statistics for continuous variables as median (95% Confidence Interval (95% CI)). All situations were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method to identify relevant prognosticators. A model of multivariable Cox proportional hazards with a priori selection of covariates was used to check for independent prognostic effects.

Results and Discussion

A total of 14 titles were selected from the literature after removing duplicates and excluding records. A total of cero records was identified from these searches which comply all requirements described before.

Series description and differences among groups

All the selected studies were relevant to the subject of this systematic review. None of the articles included were randomized controlled trials or prospective studies; all the articles were case reports and case series. Median age was 39 years old (range 13-85) with significant differences between age groups (p<0.001). We did not find remarkable variations in gender (p= 0.061), although females presenting CADASIL were noticeably less frequent and slightly less prevalent.

For the selection process in this review, cero papers fit the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Some of these studies demonstrated an advantage in pathogenesis but they did not correlated with drug therapy. The difference in results was analyzed using Analyses of Covariance (ANCOVA) and partial eta squared. The accuracy of paired pattern recall of each picture was observed, and the measurement of accuracy was defined as the hit rate.

Comments and Final Remarks

Brief comments on the pathogenesis of CADASIL

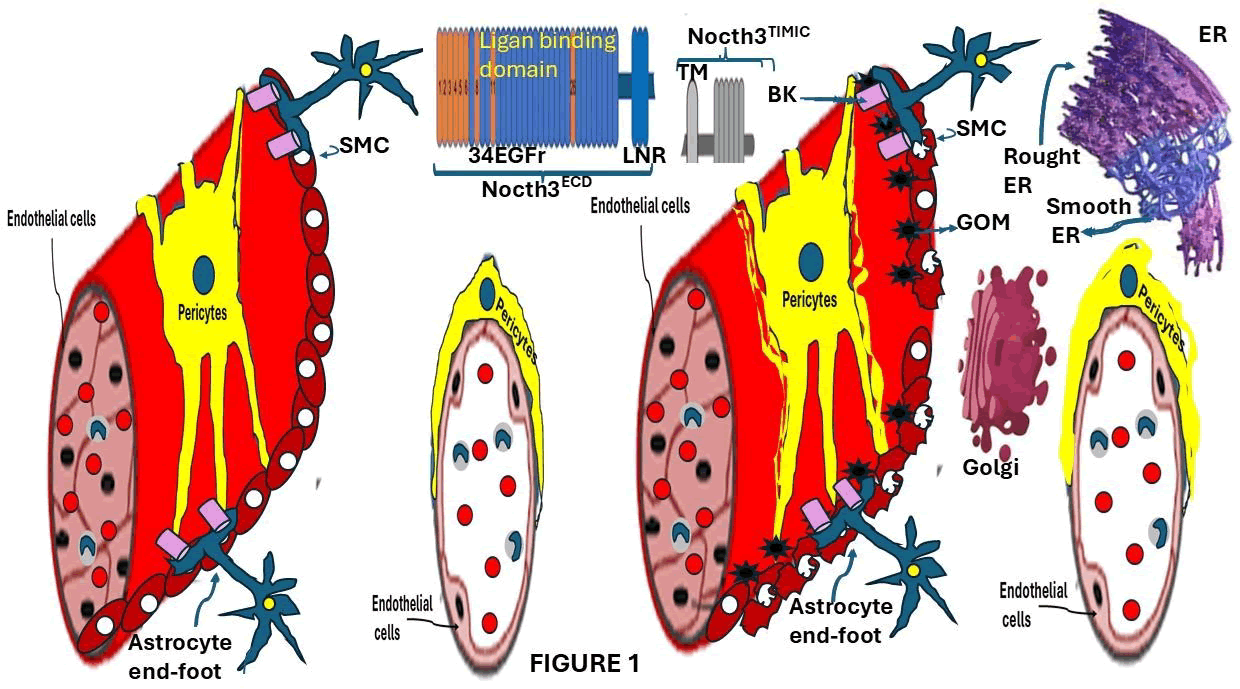

These pathological changes in Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells (aSMCs) and pericytes lead to structural abnormalities in the vessel walls, reduced vascular elasticity, and the occurrence of microbleeds. Additionally, the expansion of perivascular spaces is commonly observed, reflecting the widespread impact on pericytes, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Visual overview of the pathogenesis of CADASIL, highlighting the domains of the NOTCH3 protein, contrasting the structural changes in affected individuals brain blood vessels with those of healthy controls. High-risk Epidermal Growth Factor- Like repeats (EGFr), which are frequently involved in CADASIL, are marked in orange. The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), where this pathway begins, is thought to be disrupted in the disease. The abnormal incorporation of in the Golgi apparatus produced Latent Transforming Growth Factor Binding Protein-1 (LTBP-1) into Notch Extracellular Domain (Notch-ECD) deposits and elevated levels of Latency-Associated Peptide (LAP) in the affected blood vessels are examples of this. Dysregulation of TGF- signaling particularly impacts Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs), leading to vessel wall thickening, reduced functionality, and increased fibrosis.

Several molecules, including fibronectin, fibrillin-1, and LTBP-1, tightly regulate the availability of active TGF.

Changes in the brains capillary system also involve the breakdown and loss of pericytes, leading to disruption in the contact between endothelial cells and pericytes an essential component of vascular integrity.

Brief comment on the clinical presentations of CADASIL

White Matter Hyperintensities (WMHs), lacunar infarcts, cerebral microbleeds, and Enlarged Perivascular Spaces (EPS) are some of the most common radiological findings in CADASIL patients. The anterior temporal lobes, brainstem, thalamus, and lentiform nucleus are typically affected by lacunar lesions. In a similar vein, the external capsule, thalamus, and brainstem frequently experience microbleeds.

Additional MRI findings often include cerebral microbleeds, prominent perivascular spaces, and varying degrees of both cortical and generalized brain atrophy. Cognitive impairments, particularly in processing speed and executive function, are characteristic of the disease and often progress to Vascular Dementia (VaD) [17].

Moreover, it is hypothesized that the severity or progression of CADASIL may be influenced by the specific location of the NOTCH3 mutation. Interestingly, significant differences in clinical presentation have been observed background, suggesting additional genetic or environmental modifiers may be involved [18].

Brief comments on the role of NOTCH3 in CADASIL

However, studies have shown that mutations within the first six EGFr domains are not commonly associated with the clinical manifestation of CADASIL, suggesting these regions may not play a central role in the underlying disease mechanism.

A large-scale study conducted by Cho, et al. in 2021 involving 200,000 individuals revealed a higher than anticipated frequency of NOTCH3 mutations approximately 1 in every 450 people supporting the notion that NOTCH3 variants are more prevalent than previously believed. It is also proposed that the clinical severity and variation in small vessel disease outcomes may depend on the specific EGFr domain in which the mutation occurs.

One of the four mammals NOTCH gene homologs, NOTCH3, is essential for important developmental processes like cell proliferation, fate determination, vascular development, and programmed cell death. During Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell (VSMC) differentiation and maturation, it is primarily expressed [18,19]. The extracellular domain (NOTCH3ECD), which is made up of 34 Epidermal Growth Factor-Like repeats (EGFr), and the C-terminal portion (NOTCH3ICD), which is made up of the transmembrane and intracellular domain, are the two main parts of this protein. The ligand-binding region is primarily located between EGFr domains 10 and 11 [20].

Although most disease-associated mutations are concentrated within exons 2 through 24 regions that code for the EGFr domains some studies have also identified pathogenic variants in exons 25 to 33, outside the EGFrencoding region, suggesting these regions may also contribute to CADASIL pathology [21].

Upon ligand interaction with the NOTCH3ECD, a conformational change occurs, allowing enzymatic cleavage in the intercellular space. The protein is first broken up by the enzymes of the ADAM (A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease) family, specifically ADAM10 and ADAM17. The NOTCH3 Intracellular Domain (NOTCH3ICD) is released from the membrane following a second cleavage by -secretase. The NOTCH3ICD moves to the nucleus after breaking free, where it controls the transcription of target genes that are necessary to keep the VSMC functioning and stable [22]. According to the same researchers, the NOTCH3 genes exons 2 to 6 are known as mutation hotspots and frequently exhibit ethnic variation. Increased or decreased signaling activity can result from NOTCH3 ligand-binding domain mutations. Structure and vascular function have been linked to both types of dysregulation [18]. Additionally, Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell (VSMC) degeneration, the breakdown of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), and an increased risk of ischemic strokes have all been linked to disruptions in NOTCH3 signaling [23]. The involvement of this signaling pathway in cerebral Small Vessel Disease (cSVD), which is associated with symptoms such as stroke, cognitive decline, and leukoencephalopathy [24,25], has been further supported by clinical reports involving NOTCH3 mutations that result in reduced protein function (Table 1).

| Domain of NOTCH3 protein | Mutations in the NOTCH3 gene |

| Signal peptide | L33 del, A34V |

| EGF-like 1 | C43G, C43F, C49G, C49F, C49Y, R54C, S60C, C65S, C65Y, C67Y, W71C, R75W, R75P, C76R, C76W |

| EGF-like 2 | 77-83 del, 80-84 del, C87R, C87Y, R90C, C93F, C93Y, C93 dup,C106W, C108W, C108Y, C108R, R110C, R113Q, 114-120 del, C117F, S118C |

| EGF-like 3 | C123F, C123Y, C128Y, C128G, C128F, G131C, R133C, C134W, D139V, R141C, F142C, C144F, C144S, C144Y, S145C, C146R, C146F, C146Y, G149C, Y150C, 153-155 del, R153C, C155S, C155Y |

| EGF-like 4, calcium- binding | C162S, C162W, R169C, H170R, G171C, C174F, C174R, C174Y, S180C, R182C, C183F, C183R, C183S, C185G, C185R, Y189C, C194F, C194R, C194S, C194Y |

| EGF-like 5 | C201Y, C201R, A202E, C206Y, C206R, R207C, C209R, C212S, R213K, Y220C, C222G, C222Y, C224Y, C233S, C233Y, C233W |

| EGF-like 6, calcium-binding | 239-253 del, V237M, C240S, C245R, C251R, C251S, C251G, Y258C, C260Y, C271F |

| EGF-like 7 | S299C |

| EGF-like 8, calcium-binding | A319C, R332C, S335C, Y337C, C338R |

| EGF-like 9 | C366W, CC379S, C379R, G382C, C388Y |

| EGF-like 10, calcium-binding | C395R, G420C, R421C, P426L, C428Y, C428S |

| EGF-like 11, calcium-binding | C435R, C440G, C440S, C446S, C446F, R449C, C455R, Y465C |

| EGF-like 12, calcium-binding | C484F, C484Y, C4884G, C495Y, P496L, S497L |

| EGF-like 13, calcium-binding | C511R, C516Y, G528C, R532C, C533Y, C542Y |

| Interdomain | R544C |

| EGF-like 14, calcium-binding | C549Y, C549R, H556R, R558C, C568Y, R578C, R578H |

| EGF-like 15, calcium-binding | A587C, C591R, C597W, R607C, R607H |

| Domain of NOTCH3 protein | Mutations in the NOTCH3 gene |

| EGF-like 16, calcium- binding | R640C, V644D |

| EGF-like 17, calcium- binding | G667C, R680H |

| EGF-like 18 | Y710C, R728C |

| EGF-like 19 | R767H, C775S |

| EGF-like 20 -> EGF-like 23, calcium-binding | - |

| EGF-like 24 | G953C |

| EGF-like 25 | C977S, S978R, F984C, R985C, C988Y, C997G |

| EGF-like 26 | R1006C, C1015R, A1020P, Y1021C, W1028C, R1031C |

| EGF-like 27 | G1058C, C1061Y, D1063C, R1076C |

| EGF-like 28 | C1099Y, Y1106C, N1118Y |

| EGF-like 29, calcium-binding | H1133Q, C1157W |

| EGF-like 30, calcium- binding | V1183M |

| EGF-like 31 | R1231C, H1235L, R1242H |

| EGF-like 32 | C1250W, C1261R, C1261Y |

| EGF-like 33 | Q1297L |

| EGF-like 34 | P1357L |

| LNR 1 -> LNR 3 | - |

| HD? | L1518M, L1547V, I1586V |

| RAM? | L1691E, G1710D, R1748H, V1762M, R1837H |

| ANK 1 -> ANK 5 | A1850S, A1850D, V1952M, F1995C, P2033T, P2074L, R2109Q, A2223V |

| Source: https://www.uniprot.org/ (accessed on 19 July 2025), https://www.omim.org/entry/600276 (accessed on 19 July 2025) | |

Table 1: Mutations in the NOTCH3 gene

Proteomic studies conducted on brain arteries from both human and animal models enriched with NOTCH Extracellular Domain (ECD) have identified the presence of vitronectin and TIMP3 in CADASIL cases, which were absent in healthy controls. Notably, TIMP3 expression is significantly elevated in postmortem brain tissue from individuals with CADASIL. These discoveries offer further insight into the molecular mechanisms driving CADASIL pathology [26].

Clinical symptoms such as ischemic stroke, cognitive decline, and leukoencephalopathy have been strongly associated with specific mutations in the cerebral Small Vessel Disease (cSVD) [18].

NOTCH3 mutations vary in type, with the most common involving alterations in cysteine residues. Such evidence reinforces the crucial role of cysteine pairing and disulfide bond formation in maintaining proper NOTCH3 structure and function.

However, there are still a lot of unknowns, such as the effects of amino acid substitutions, the full range of cysteine-related mutations, their severity, and the pathological effects of free or unpaired cysteine residues [27]. Among these, mutations that alter cysteine residues are typically highlighted in red, while cysteine-sparing mutations mutations that do not alter cysteine residues are highlighted in blue. The NOTCH3 protein structure also includes other key domains such as EGF (Epidermal Growth Factor-like repeats), LNR (LIN- 12/Notch Repeats), NRR (Negative Regulatory Region), RAM (RBP-Jk-Associated Molecule domain). Although cysteine-sparing mutations have also been identified and studied, the majority of research focuses on mutations that alter cysteine [28]. However, these cases frequently involve milder symptoms and a later disease onset. Asian populations seem to have more of these mutations, which points to potential ethnic differences in the distribution and effects of particular NOTCH3 variants [11,29]. The clinical manifestation of CADASIL is influenced by both genetic and non-genetic factors. The influence of environmental or lifestyle factors is supported by studies involving families with the same NOTCH3 mutation but different severity of symptoms [30]. Smoking and high blood pressure, for example, have been shown to worsen vascular reactivity and make the arteries stiffer.

These factors can significantly exacerbate CADASIL progression by intensifying the vascular stress on cerebral Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs), which are already compromised by NOTCH3 mutations [31].

Cerebral VSMCs are highly specialized cells that form the structural foundation of brain blood vessels. They are essential in regulating cerebral blood flow and maintaining vascular tone. Through their ability to contract and relax in response to various signals, VSMCs help ensure that the brain receives a sufficient blood supply to meet its metabolic needs.

Some researchers have proposed that-secretase-mediated cleavage of NOTCH3 results in the release of the NOTCH3 Intracellular Domain (ICD) [32]. Variations in the S1 cleavage process have also been observed in certain mutant forms of human and mouse NOTCH3, including variants such as p.Arg142Cys, p.Arg133Cys, p.Cys183Arg, and p.Cys187Arg [6]. These mutations are associated with a reduced level of S1-cleaved NOTCH3 receptors, which impairs the presentation of the receptor on the cell surface and leads to abnormal intracellular accumulation, even though ligand-induced signaling remains functionally active [6,33].

While CADASIL is typically caused by a single heterozygous mutation in the NOTCH3 gene, some studies have identified patients with homozygous mutations [34]. Although individuals with homozygous mutations sometimes exhibit more pronounced clinical symptoms compared to heterozygous cases, the evidence on this distinction remains inconclusive, with no universal consensus among researchers [35].

Further investigations have emphasized that the NOTCH3 signaling pathway is one of the most evolutionarily conserved mechanisms across species and serves as a central pathway in CADASIL pathogenesis. Mutations linked to CADASIL have been shown to increase the multimerization of the NOTCH3 protein, contributing to disease development. A cascade that includes ligand binding, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and receptor ubiquitination is initiated by the interaction between NOTCH receptors and ligands from the Delta/Serrate/ Lag-2 (DSL) family [36]. The activation of target genes in Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells (ASMCs) by NOTCH3 and the transcription factor RBP-J has been demonstrated in additional studies [37].

The NOTCH3 receptor undergoes a series of complex processes involving activation and cleavage steps to function properly. Under normal conditions, in the absence of mutations, the NOTCH3 receptor binds to its ligand, initiating a cascade that includes clathrin-dependent endocytosis of the NOTCH3 Transmembrane-Intracellular Complex (N3 TMIC). Following internalization, where it activates downstream target gene expression.

When NOTCH3 is absent, the signaling pathway is disrupted, leading to reduced RhoA activity. This suppression results in decreased activation of Rho kinase and, consequently, lower levels of myosin phosphorylation, which can impair vascular tone regulation.

However, the ligand-binding process is hindered by mutations in the extracellular domain of the receptor, such as p.Cys428Ser and p.Cys455Arg. The downstream signaling mechanism is disrupted by this. NOTCH3 Extracellular Domain (N3ECD) multimers, which deposit as Granular Osmiophilic Material (GOM) within the basement membrane, are also accelerated by these mutations. In addition, abnormal processing and impaired clearance of the mutant NOTCH3 ICD can result in the formation of intracellular aggregates, which can cause Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress, cell death, and dysfunctional VSMC growth. The degeneration of white matter seen in CADASIL is exacerbated by the presence of GOM deposits, which may impede intramural periarterial drainage and further disrupt the function of VSMCs. Moreover, the NOTCH3 signaling pathway is closely linked to TGF- signaling through its interaction with Latent TGF- Binding Protein 1 (LTBP-1) in GOM, as well as with the RhoA pathway, both of which play essential roles in regulating vascular tone and driving the pathogenesis of CADASIL [38].

The regulation of NOTCH signaling is a complicated process that requires multiple control layers. The destabilization of the Negative Regulatory Region (NRR), ligand-driven endocytosis, the assembly of repressor complexes in the nucleus, and the equilibrium between the activation and inhibition of receptors are important regulatory mechanisms [38]. Regulated Intramembrane Proteolysis (RIP), which makes it easier for the NOTCH3 intracellular domain (NOTCH3ICD) to be released upon ligand binding, is a crucial step in the activation of NOTCH proteins. This begins with the NRR being first cleaved by an ADAM-family protease, then the membrane itself is cleaved again by a secretase.

These steps are essential because NOTCH receptors remain inactive in the absence of ligands. The structure and stability of the NRR are influenced by calcium ions, and its destabilization can potentially activate NOTCH signaling even without ligand interaction.

Ligand ubiquitination is another important step, as it recruits the endocytic adaptor protein Epsin, promoting clathrin-mediated endocytosis [39]. Moreover, NOTCH ligands are capable of moving laterally across the plasma membrane, which can enhance signaling by increasing the density of receptor-ligand interactions at points of cell-cell contact.

The NOTCH3ICD is cleaved and released into the cytoplasm before moving to the nucleus to form the NOTCH Transcriptional Complex (NTC) with co-activators. Not only does this complex initiate transcriptional activation, but it also interacts with the immunoglobulin kappa J region Recombination Signal-Binding Protein (RBPJ).

According to research, the presence of NOTCH3ICD makes it easier for both activating and repressing complexes to get to specific gene targets. This dynamic interaction allows the NTC to bind dimerically to sequence-paired DNA sites, enabling precise modulation of gene expression in response to signaling cues [40,41].

Several studies have shown that different NOTCH ligands influence receptor activity and define distinct regions of receptor responsiveness [42]. An additional layer of complexity is introduced by cis-inhibition, a mechanism in which ligands expressed within the same cell as their corresponding receptors can inhibit signaling. This occurs due to the structural arrangement of ligands and receptors in an anti-parallel configuration, which prevents the mechanical pulling force typically required to activate the receptor [43,44].

In 2022, studies confirmed that NOTCH3 is essential for the survival of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) and for vascular repair processes following injury [45]. Earlier investigations comparing the NOTCH3 R142C mutant with the wild-type form observed a reduction in receptor activity at the cell surface and a decrease in S1 cleavage in the R142C variant. This mutation also promotes the formation of intracellular aggregates resembling aggresomes and suggests disruptions in receptor trafficking through the endoplasmic reticulum [46]. However, additional evidence has shown that, despite these alterations, the R142C mutation does not impair the receptors ability to respond to ligand stimulation in all contexts, while other mutations may indeed reduce ligand-induced activation of NOTCH3 signaling.

Different mutations appear to disrupt NOTCH3 function through distinct mechanisms. For instance, the C428S variant demonstrates a loss of binding to the Jagged1 ligand, indicating a defect in ligand interaction. In contrast, the C542Y mutation retains ligand-binding ability but exhibits reduced surface expression of the receptor. Meanwhile, mutations such as R90C, C212S, and R1006C maintain both Jagged1 binding and signaling function at near-normal levels [10].

Further research has revealed that the NOTCH3 pathway controls the expression of specific molecular markers such as EphB4 and EphrinB2, which are expressed in both VSMCs and Endothelial Cells (ECs) [47]. Disruption of NOTCH3 signaling in VSMCs results in significant cerebrovascular abnormalities, including malformed anastomoses, asymmetry in vessel diameter, faulty arterial patterning, and poor development of collateral vessels in the circle of Willis. Notably, reduced EphB2 activity in the VSMCs of mutant cerebral vessels underscores the essential role of NOTCH3 in arteriolar development.

These results emphasize how important NOTCH3 is for supporting cerebral blood flow and maintaining healthy cerebrovascular architecture, particularly in ischemic conditions [10]. Using a mouse model, Baron-Menguy and colleagues investigated the role of NOTCH3 in arterial physiology in 2017. The significance of NOTCH3 s role in regulating vascular tone and responsiveness to hemodynamic changes is underscored by the fact that its absence significantly impaired flow-mediated dilation and pressure responses in some arteries [48]. In vertebrates, CSL (RBPJ) plays a crucial role in NOTCH3 signaling. This role is highly context-dependent and involves intricate molecular interactions. One such interaction is with L3MBTL3, a member of the MBT protein family, which partners with RBPJ via its N-terminal domain. The histone demethylase KDM1A is recruited by this complex, which binds to chromatin and causes transcriptional repression of NOTCH target genes. Even though L3MBTL3 and RBPJ have a low affinity for binding, the presence of the NOTCH Intracellular Domain (NOTCHICD) significantly enhances this interaction. L3MBTL3 plays a critical role in modulating gene expression by facilitating KDM1A dependent demethylation of H3K4me2, thereby repressing target gene transcription [49].

Research into NOTCH signaling in Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)-activated macrophages has revealed distinct roles for different ligands. Delta-Like Ligand 4 (DLL4) was shown to promote NOTCH signaling, while Jagged1 exerted inhibitory effects. ADAM10 was identified as a crucial regulator in this pathway, facilitating receptor activation. The study also distinguished the roles of NOTCH3, NOTCH2, and NOTCH1 in macrophage behavior, with NOTCH3 being uniquely involved in regulating NF-B activity, potentially via activation of the p38 signaling pathway. Structural differences between NOTCH3 and other NOTCH receptors were noted, including a faster activation profile. The study concluded that NOTCH3 is predominantly active during the early phases of macrophage activation, while NOTCH1 becomes more prominent in later stages [11].

Multiple studies have shown that mutations in the NOTCH3 gene result in abnormal accumulation of the NOTCH3 protein. This accumulation is associated with the degeneration of Smooth Muscle Cells (SMCs) in small cerebral vessels, contributing to early-onset strokes and migraine headaches, sometimes accompanied by aura [50]. Recent studies [51] confirm that these mutations cause structural changes in the protein and disrupt the normal signaling function of NOTCH3 that are directly linked to the development of CADASIL. Atypical NOTCH3 mutations have also been shown to cause a wide range of clinical symptoms, highlighting the significance of mutationspecific factors in diagnosis and treatment [51]. Evidence also points to the involvement of the Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-) pathway in CADASIL progression. Vascular smooth muscle cell damage and excessive fibrotic thickening of blood vessels are both caused by impaired TGF-signaling. It is believed that altered TGFbioavailability and its sequestration by latent TGF-Binding Protein 1 (LTBP-1) are significant pathological drivers [52,53].

To fully understand CADASIL progression, several additional factors must be considered, including NOTCH3 trans-endocytosis, the deposition of Granular Osmiophilic Material (GOM), and downstream signaling interactions with the TGF- pathway. Proteins such as Nidogen, Emilin, and dysregulated LTBP-1 all of which play roles in TGF- biology have been implicated in the disease mechanism, suggesting a broader network of molecular disruptions contributing to CADASIL development.

Brief comments on diagnostic procedures

CADASIL remains significantly underdiagnosed due to a range of challenges spanning clinical presentation, genetic complexity, and gaps in medical education. Clinically, CADASIL shares overlapping features with several other hereditary Cerebral Small Vessel Diseases (CSVDs), which complicates accurate diagnosis. For example, Fabry disease, though distinguishable by signs like angiokeratomas and albuminuria, shares neurological symptoms with CADASIL, including small vessel ischemic strokes. Similarly, HTRA1-related CSVD and CARASIL exhibit white matter abnormalities akin to those seen in CADASIL, but are also associated with systemic signs such as skeletal deformities and alopecia, which can aid in differentiation. Other conditions, like RVCL-S and HANAC syndrome, also present with stroke risk but are differentiated by unique systemic features [54].

Adding further complexity, CADASIL displays considerable variability in age of onset and symptom severity. However, less typical presentations such as confusional aura or encephalopathy can mimic psychiatric illnesses or seizure disorders. Ischemic strokes generally appear by age 49, yet around 20% of patients experience them before age 40. Neuroimaging findings such as anterior temporal lobe white matter hyperintensities and lacunar infarcts are often mistaken for normal aging or unrelated cerebrovascular changes.

Unlike other genetic conditions such as Fabry disease or RVCL-S, CADASIL typically lacks distinct nonneurological features, which further hampers recognition. Psychiatric symptoms, including apathy and depression, are sometimes misdiagnosed as primary mental health disorders, especially when cognitive decline is present. Although stroke specialists may recognize characteristic vascular patterns, it s notable that up to 12% of strokes in CADASIL patients occur without traditional vascular risk factors, which can obscure the underlying genetic cause.

The NOTCH3 genes cysteine-sparing mutations add another layer of diagnostic uncertainty [63]. Although hallmark lesions in the anterior temporal lobes are identified by MRI in about 90% of CADASIL cases, this requires a high level of neuroimaging expertise and frequently a customized imaging protocol. Family history is frequently overlooked, particularly if it involves migraines or earlyonset strokes, delaying appropriate diagnostic followup [10]. Due to these diagnostic delays, many patients experience preventable complications. As many as 75% of individuals with CADASIL will suffer recurrent strokes, often leading to cognitive impairment by their 40s. To address this diagnostic gap, we propose a multifaceted approach. This includes dedicated training in CADASIL recognition for neurologists and psychiatrists, enhanced neuroimaging protocols, in-depth investigation of immune and NOTCH3 signaling pathways, and expanded access to genetic counseling. Furthermore, ongoing research into novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets is essential to improve early detection and patient outcomes.

Brief comments on drugs/gene therapy

Gaining a comprehensive understanding of CADASIL requires an in-depth exploration of the interplay between signaling pathways, genetic mutations, and potential disease-modifying genes. This knowledge is essential for advancing therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating disease progression and improving patient care.

Recent findings have somewhat shifted focus away from the broader genetic framework by identifying specific disease-modifying genes such as RNF213, which has drawn attention to the molecular mechanisms driving CADASIL pathophysiology [55]. In light of this, we propose that treatment strategies should emphasize modulation of critical elements within these disrupted pathways. This approach aligns with recommendations from previous research emphasizing the importance of targeting diseasespecific molecular dysfunctions to optimize outcomes for affected individuals [56].

By activating phosphorylated Akt signaling, a crucial promoter of cell viability, this peptide hormone increases OPC survival [57]. Adrenomedullin also plays a role in angiogenesis from pericytes and modulates inflammation by suppressing excessive microglial activity [58]. These mechanisms are especially important in the CADASIL disease process. Innovative therapeutic strategies targeting the NOTCH3 signaling pathway are currently gaining traction, especially due to their capacity to directly address the underlying molecular abnormalities in CADASIL. The A13 agonist antibody, which triggers NOTCH3 signaling, is one promising strategy. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that this antibody helps normalize biomarkers such as HTRA1 and extracellular NOTCH3 (NOTCH3-ECD), while also preserving pericyte integrity, an essential component of cerebrovascular health [59]. The vascular structure and function may be enhanced by the A13 antibodys ability to restore signaling homeostasis [60]. Modifying the TGF-pathway, which is essential for maintaining the function of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs), is another promising treatment development direction. This pathway may be therapeutically targeted to lessen the disease burden by reducing vascular fibrosis and increasing vascular flexibility [61]. In conclusion, these emerging therapeutic avenues underscore the importance of prioritizing NOTCH3 signaling modulation in the clinical management of CADASIL and related small vessel diseases. A targeted approach has the potential to not only address the fundamental molecular disruptions that are driving disease progression but also to control disease symptoms.

Commonest location of ischemic lesions reported in CADASIL patients

As has been enunciated before the commonest location of the ischemic lesions found in reported cases is listed in the following table (Table 2).

| Location | Number of lesions | Percentage |

| Corona radiata | 120 | 41.00% |

| Juxta subcortex | 73 | 25% |

| Centrum semioval | 58 | 20% |

| Splenium | 41 | 14% |

| Internal capsule | 32 | 11% |

| Basal ganglia | 26 | 9% |

| Thalamus | 23 | 8% |

| Midbrain, pons | 20 | 7% |

| Cerebellum | 17 | 6% |

Table 2: Distribution of acute ischemic stroke lesion

New additional information on CADASIL

Recently, Lee, et al. determined serum Neurofilament Light (NfL) chain levels using a commercially available Simoa reagent kit (NFlightTM advantage Kit) on the Simoa HD-X Analyzer (Quanterix, Lexington, MA, USA) at baseline and after three years in the outpatient clinic at Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, South Korea, from October 2018 to October 2019, to study the clinical significance of longitudinal changes in serum NfL levels in a group of patients presenting CADASIL. However, because they found a predominant genetic variant (p.Arg544Cys) in >90% of the cases and because a small number of patients limited this investigation, their findings cannot apply to other cases with the common sporadic cerebral SVD or CADASIL [62].

In this year, Romero and Holguin reported an exceptional case of 70-old type 2 diabetic lady with past medical history of dyslipidaemia and hypothyroidism without history of cognitive decline or migraine headache with confirmed Variant c.421c>T; p.Arg141Cys heterozygous NOTCH3 probably pathogenic Code 404841 GP plus the classic MRI findings consistent with CADASIL highlighting the importance of taken into consideration CADASIL despite any atypical presentations in older patients. Soon after, other investigators reported a 50-yearold lady complaining of a longstanding history of migraine with aura. Genetic testing identified a rare heterozygous NOTCH3 variant (c.6102dup, p.Gly2035Argfs*60); apart from that, cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed increased myelin basic protein, 4 oligoclonal bands, and an elevated IgG index, suggesting an inflammatory condition. Her visual evoked potentials documented no evidence of tract impairment or optic nerve. Then, a rare NOTCH3 c.6102dup variant potentially associated with an inflammatory phenotype was confirmed, plus comorbidity with another demyelinating central nervous system disease was proved [63].

In a study conducted by Park, et al. this year, factors linked to Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) in CADASIL patients were investigated. The study included 141 individuals, of whom 70 (49.6%) were confirmed to have experienced AIS. The researchers reported no significant differences in traditional vascular risk factors between those with and without AIS. However, patients in the AIS group showed a higher frequency and number of lacunar infarcts (p<0.001), along with more pronounced white matter changes (p=0.007) [64]. At the same time, Wang and colleagues constructed a CSVD disease model by induction on mononuclear cells in CADASIL patients [65].

Men et al. studied the occurrence, prognosis and risk factors, of Acute Cerebral Microinfarcts (ACMIs) with a prevalence of 20% observed in their cohort mainly distributed in the corona radiata and the majority of ACMIs disappear at one year of follow up despite a worse functional outcome after one year compared and a remarkable swift decline in quality of life from baseline with those without ACMIs [66].

Recently, a group of investigators matched thirty seven patients presenting CADASIL with one hundred and four controls and found that hypertensive Hispanic/Latino patients p<0.02) were smokers. Still, they did not find a difference in the diameter of ICA (p=0.73) [67].

On the other side, Hu and collaborators studied one 190 patients with CADASIL and found that one 179 of them had sporadic CSVD and 43 presented ICH most commonly locate in the thalamus (40.3%), followed by basal ganglia (32.3%) and temporal lobe (8.1%) [68].

Other authors seeking a better understanding of CADASIL explored some advances in research on the molecular mechanisms of this condition under different mutations. This investigation mainly focused on elucidating the relationship between clinical phenotypes and CADASIL and identified at least five factors associated with the severity of clinical features in CADASIL: Variant types, environmental factors, mutation location, epigenetic regulation, and polygenic interactions [69].

Brief comments about the NOTCH3 mutation effect on the Glymphatic System

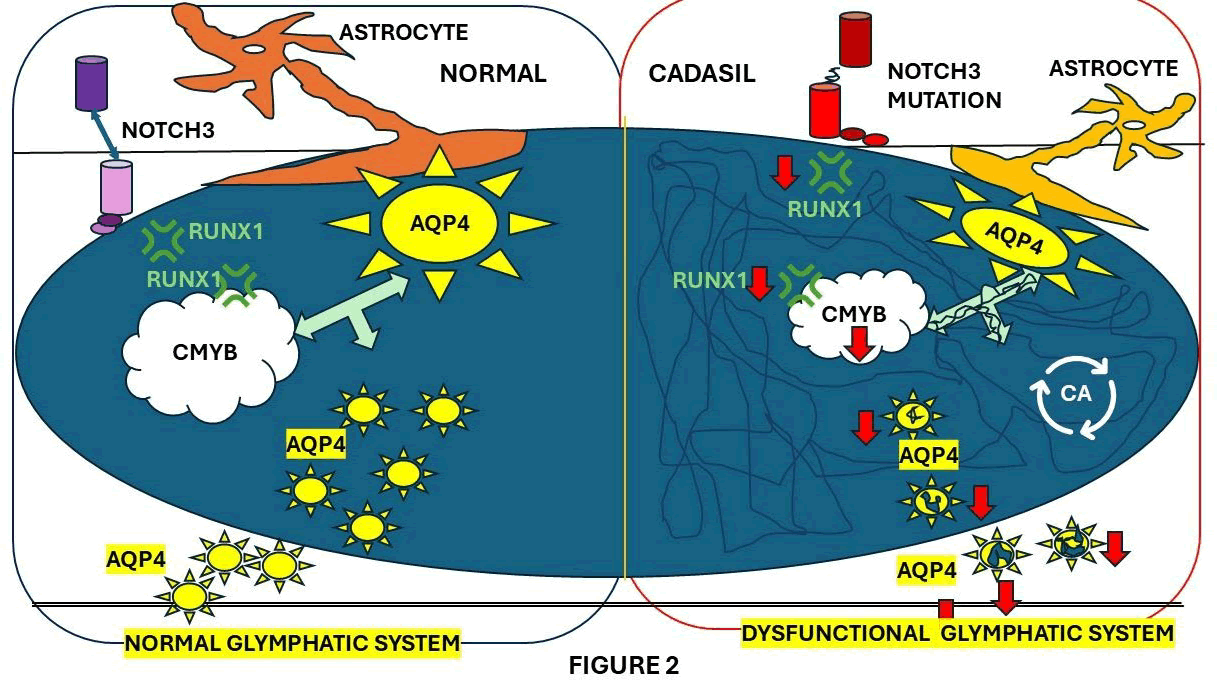

Li, et al. studied the role of the Glymphatic System (GS) of CADASIL. They explored a potential therapeutic mechanism to improve the glymphatic system, which is a network of perivascular tunnels wrapped by astrocyte end feet. These researchers found that perivascular space enlargement was associated with brain atrophy in CADASIL patients. This suggests that glymphatic impairment is the cause of advanced brain senescence. Besides pericytes, NOTCH3 is expressed in end plate astrocytes, which upregulates RUNX1 expression.

Figure 2 shows how NOTCH3-RUNX1-CMYB signaling regulates AQP4 activity on a mechanistic level. The same researchers came to the conclusion that reinforcing AQP4 activity in astrocyte end plates with an adeno-associated virus-based treatment reactivates GS functions in CADASIL mice, thereby further preventing brain senescence [70].

Figure 2: Proposed mechanism of glymphatic dysfunction in CADASIL.

As a result, glymphatic functions are impaired. The NOTCH3 mutation in astrocytes suppresses RUNX1-CMYB-AQP4 signaling, resulting in decreased AQP4 expression. In CADASIL mice, astrocyte-targeting AAV increases AQP4 expression and restores glymphatic functions, thereby preventing brain senescence. RUNX1 is a NOTCH target gene with the ability to mediate gene transcription and translocate into the nucleus with various cofactors, including CMYB, as established by the same authors. Notch activation also upregulates RUNX1 expression. NOTCH-CMYB pathway, as represented in Figure XX, is implicated in stem cell development. However, little research has been done on the functional changes that CADASIL causes to NOTCH downstream pathways, including RUNX1-CMYB signaling. On the other hand, has been broadly reported that cases with CADASIL are associated with brain atrophy, which is one of the most remarkable neuroimaging features of CADASIL.

The GS is a network of perivascular tunnels that the brain uses to remove waste [71]. These tunnels are covered in astrocyte end feet. Aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel that is found on the end feet of astrocytes, is responsible for the rapid transport of Interstitial Fluid (ISF) by GS [71]. Maintaining homeostasis in the brain necessitates GS function, whereas GS dysfunction exacerbates neurofunctional deficits [71]. Neuroimaging has shown that GS dysfunction could result in an expansion of the perivascular space [71]. Accumulative evidence shows that increased EPVS burden is commonly manifested [71].

We hypothesized that CADASIL may damage the GS by low AQP4 expression secondary to reduced activation of NOTCH3B signaling, leading to brain senescence. Therefore, enhancing the GS function might be a novel therapeutic choice against CNS senility in CADASIL. Other authors reported that EGFr 1–6 is associated with Other authors reported that EGFr 1–6 is associated with elevated NOTCH3 expression levels and dysfunctional cytoskeletal reorganization mechanisms at the pluripotent stem cell level, which are related to CADASIL severity and the clinical association between the pathogenic NOTCH3 variants [72].

Jolly et al. reported the prevalence of fatigue in CADASIL based on the relationship of fatigue with depression and cognitive impairment, the MRI markers of SVD, plus its association with clinical and demographic factors [73-75].

Conclusions

The NOTCH3 signaling pathway plays a vital role in the func on of VSMCs and the integrity of the walls of blood vessels. We finally hypothesized that mutations in the NOTCH3 gene disrupt standard vascular architecture and blood vessel function, leading to vascular injuries by protein deposits, which are characteristics of CADASIL. Until proven otherwise, the TGF-β signaling pathway plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of CADASIL. Progression of CADASIL is related to the deregula on of TGF-β signaling that is closely associated with the overexpression of LAP within the affected vessels and the recruitment of LTBP-1 into NOTCH ECD deposits, modifying TGF-β bioavailability. Unfortunately, there is no specific therapy or cure for CADASIL apart from non-pharmacological treatment, including practical help, like supportive care, emo onal support, and counselling, for affected people and their families. Symptoma c and prophylactic treatment for migraine headache, such as tricyclic an depressant, beta-blockers, aerobic exercise, and others, is strongly recommended. We also suggest forthcoming investigations based on larger patient cohorts and more extended follow-up periods to define outcomes that matier to patients and to identify all the potential risks, genetic screening, and advanced imaging like 7 T-MRI, which will support novel therapeutic procedures.

Limitations

We afford some limitations for this systematic review that must be acknowledged. The main limitations were related to most of the data obtained from case reports and series, which may limit the generalizability of the findings and introduce bias. We also found significant variability in the description of the pathogenesis of CADASIL. Therefore, this heterogeneity complicates the drawing of definitive conclusions based on the synthesis of data. The presence of bias towards reporting cases with severe or unusual presentations at different age group, leading to an overrepresentation of specific drug therapy associations. Limitations also arise in this review structure. There were not studies that met all criteria. Further reviews should expand the criteria.

Funding Information

The authors received no funds to perform the present research.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted using the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, the Italian and US privacy and sensitive data laws, and the internal regulations for retrospective studies of the Otolaryngology Section at Padova University and Brescia University.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained the informed consent from the case involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Thozama Dubula, Head of Department on Internal Medicine and Therapeutic for his unconditional support in the management of this patient.

References

- Y. Zhang, A. Parikh, S. Qian, Migraine and stroke, Stroke Vasc Neurol, 2(2017): 160–167.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O. Szymanowicz, I. Korczowska-Lacka, B. Slowikowski, M. Wiszniewska, A. Piotrowska, et al. Headache and NOTCH3 gene variants in patients with CADASIL, Neurol Int, 15(2023).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- H. Chabriat, A. Joutel, M. Dichgans, E. Tournier-Lasserve, M. G. Bousser, CADASIL, Lancet Neurol, 8(2009):643–653.

- R. Kopan, M. X. Ilagan, The canonical Notch signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism, Cell, 137(2009):216–233.

- Z. Aburjania, S. Jang, J. Whitt, R. Jaskula-Stzul, H. Chen, et al. The role of Notch3 in cancer, Oncologist, 23(2018):900–911.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Joutel, K. Vahedi, C. Corpechot, A. Troesch, H. Chabriat, et al. Strong clustering and stereotyped nature of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL patients, Lancet, 350(1997):1511–1515.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Yamamoto, L. J. Craggs, A. Watanabe, T. Booth, J. Attems, et al. Brain microvascular accumulation and distribution of the NOTCH3 ectodomain and granular osmiophilic material in CADASIL, J Neuropathol. Exp Neurol, 72(2013):416–431.

- T. Haritunians, T. Chow, R. P. De Lange, J. T. Nichols, D. Ghavimi, et al. Functional analysis of a recurrent missense mutation in Notch3 in CADASIL, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 76(2005):1242–1248.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. W. Rutten, H. G. Dauwerse, G. Gravesteijn, M. J. van Belzen, J. van der Grond, et al. Archetypal NOTCH3 mutations frequent in public exome: Implications for CADASIL, Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 3(2016):844–853.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O. Szymanowicz, I. Korczowska-Lacka, B. Slowikowski, M. Wiszniewska, A. Piotrowska, et al. Headache and NOTCH3 gene variants in patients with CADASIL, Neurol Int, 15(2023):1238–1252.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- P. Heidari, M. Taghizadeh, O. Vakili, Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms involved in the onset and progression of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL); a focus on Notch3 signaling, J Headache Pain, 26 (2025):96.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- W. Ni, Y. Zhang, L. Zhang, J. J. Xie, H. F. Li, et al. Genetic spectrum of NOTCH3 and clinical phenotype of CADASIL patients in different populations, CNS Neurosci Ther, 28(2022):1779–1789.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Panahi, M. N. Yousefi, E. B. Samuelsson, K. G. Coupland, C. Forsell, et al. Differences in proliferation rate between CADASIL and control vascular smooth muscle cells are related to increased TGF beta expression, J Cell Mol Med, 22(2018):3016–3024.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. Monet-Lepretre, I. Haddad, C. Baron-Menguy, M. Fouillot-Panchal, M. Riani, et al. Abnormal recruitment of extracellular matrix proteins by excess Notch3 ECD: A new pathomechanism in CADASIL, Brain, 136(2013):1830–1845.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. Kast, P. Hanecker, N. Beaufort, A. Giese, A. Joutel, et al. Sequestration of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 into CADASIL-related Notch3-ECD deposits, Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2(2014):96.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- I. Mizuta, Y. Nakao-Azuma, H. Yoshida, M. Yamaguchi, T. Mizuno. Progress to clarify how NOTCH3 mutations lead to CADASIL, a hereditary cerebral small vessel disease, Biomolecules, 14(2024):127.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- N. Sukhonpanich, F. Koohi, A. A. Jolly, Changes in the prognosis of CADASIL over time: A 23-year study in 555 individuals, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 96(2025):7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Yamamoto, Y. C. Liao, Y. C. Lee, M. Ihara, J. C. Choi, Update on the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and biomarkers of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, J Clin Neurol, 19(2023):12–27.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- B. P. H. Cho, S. Nannoni, E. L. Harshfield, D. Tozer, et al. NOTCH3 variants are more common than expected in the general population and associated with stroke and vascular dementia: An analysis of 200,000 participants, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 92(2021):694–701.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. W. Rutten, J. Haan, G. M. Terwindt, S. G. van Duinen, E. M. Boon, et al. Interpretation of NOTCH3 mutations in the diagnosis of CADASIL, Expert Rev Mol Diagn, 14(2014):593–603.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E. Papakonstantinou, F. Bacopoulou, D. Brouzas, V. Megalooikonomou, D. D'Elia, et al. NOTCH3 and CADASIL syndrome: A genetic and structural overview, EMBnet J, 24(2019).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- L. Y. Hung, T. K. Ling, N. K. C. Lau, W. L. Cheung, Y. K. Chong, et al. Genetic diagnosis of CADASIL in three Hong Kong Chinese patients: A novel mutation within the intracellular domain of NOTCH3, J Clin Neurosci, 56(2018):95–100.

- E. A. Ferrante, C. D. Cudrici, M. Boehm. CADASIL: New advances in basic science and clinical perspectives, Curr Opin Hematol, 26(2019):193–198.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Schoemaker, J. F. Arboleda-Velasquez, Notch3 signaling and aggregation as targets for the treatment of CADASIL and other NOTCH3-associated small-vessel diseases, Am J Pathol, 191(2021):1856–1870.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- D. Sprinzak, S. C. Blacklow, Biophysics of Notch signaling, Annu Rev Biophys, 50(2021):157–189.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed].

- W. Liu, J. Zhang, J. Li, S. Jia, Y. Wang, First report of a p.Cys484Tyr Notch3 mutation in a CADASIL patient with acute bilateral multiple subcortical infarcts—case report and brief review, BMC Neurol, 24(2024):77.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S. J. Lee, X. Zhang, E. Wu, R. Sukpraphrute, C. Sukpraphrute, et al. Structural changes in NOTCH3 induced by CADASIL mutations: Role of cysteine and non-cysteine alterations, J Biol Chem, 299(2023):104838.

- H. Chabriat, O. S. Lesnik, Cognition, mood and behavior in CADASIL, Cereb Circ Cogn Behav, 3(2022):100043.

- L. Huang, W. Li, Y. Li, C. Song, P. Wang, et al. A novel cysteine-sparing G73A mutation of NOTCH3 in a Chinese CADASIL family, Neurogenetics, 21(2020):39–49.

- X. Liu, Y. Zuo, W. Sun, W. Zhang, H. Lv, et al. The genetic spectrum and the evaluation of CADASIL screening scale in Chinese patients with NOTCH3 mutations, J Neurol Sci, 354(2015):63–69.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- M. E. Safar, R. Asmar, A. Benetos, J. Blacher, P. Boutouyrie, et al. Interaction between hypertension and arterial stiffness, Hypertension, 72(2018):796–805.

- A. J. Groot, R. Habets, S. Yahyanejad, C.M. Hodin, K. Reiss, et al. Regulated proteolysis of NOTCH2 and NOTCH3 receptors by ADAM10 and presenilins, Mol Cell Biol, 34(2014):2822–2832.

- W. C. Low, Y. Santa, K. Takahashi, T. Tabira, R.N. Kalaria. CADASIL-causing mutations do not alter Notch3 receptor processing and activation, NeuroReport, 17(2006):945–949.

- M. Mukai, I. Mizuta, A. Ueda, D. Nakashima, Y. Kushimura, et al. A Japanese CADASIL patient with homozygous NOTCH3 p. Arg544Cys mutation confirmed pathologically, J Neurol Sci, 394(2018):38–40.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- R. He, H.Li, Y.Sun, M. Chen, L.Wang, et al. Homozygous NOTCH3 p.R587C mutation in Chinese patients with CADASIL: A case report, BMC Neurol, 20(2020):72.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J.C.V. da Silva, L. Chimelli, F.K. Sudo, E.Engelhardt, CADASIL–genetic and ultrastructural diagnosis, Case report, Dement Neuropsychol, 9(2015):428–432.

- X.H. Li, F.T. Yin, X.H. Zhou, A.H. Zhang, H. Sun, et al. The signaling pathways and targets of natural compounds from traditional Chinese medicine in treating ischemic stroke, Molecules, 27(2022).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.M. Drazyk, R.Y.Y. Tan, J. Tay, M. Traylor, T. Das, et al. Encephalopathy in a large cohort of British CADASIL patients, Stroke, 50(2019):283–290.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- G. Gravesteijn, J.G. Dauwerse, M. Overzier, G.Brouwer, I. Hegeman, et al. Naturally occurring NOTCH3 exon skipping attenuates NOTCH3 protein aggregation and disease severity in CADASIL patients, Hum Mol Genet, 29(2020):1853–1863.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- W.C. Yen, M.M. Fischer, F. Axelrod, C.Bond, J.Cain, et al. Targeting Notch signaling with a Notch2/Notch3 antagonist (tarextumab) inhibits tumor growth and decreases tumor-initiating cell frequency, Clin Cancer Res, 21(2015):2084–2095.

- B. Zhou, W. Lin, Y. Long, Y. Yang, H. Zhang, et al. Notch signaling pathway: Architecture, disease, and therapeutics, Signal Transduct Target Ther, 7(2022):95.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- K. Bruckner, L. Perez, H. Clausen, S. Cohen, Glycosyltransferase activity of Fringe modulates Notch-Delta interactions, Nature, 406(2000):411–415.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- S.Lopez-Lopez, E.M.Monsalve, M.J.Romero de Avila, J.Gonzalez-Gomez, N.Hernandez de Leon, et al. NOTCH3 signaling is essential for NF-kappaB activation in TLR-activated macrophages,” Sci Rep, 10(2020):14839.

- A. Joutel. The NOTCH3ECD cascade hypothesis of cerebral autosomal-dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy disease, Neurol Clin Neurosci, 3(2014):1–6.

- A. H. Campos, W. Wang, M. J. Pollman, G. H. Gibbons, Determinants of Notch3 receptor expression and signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells: Implications in cell-cycle regulation, Circ Res, 91(2002):999–1006.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E.J.Belin de Chantemele, K.Retailleau, F.Pinaud, E.Vessieres, A.Bocquet, et al. Notch3 is a major regulator of vascular tone in cerebral and tail resistance arteries, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 28(2008):2216–2224.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A. Proweller, A. C. Wright, D. Horng, L. Cheng, M. M. Lu, et al. Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells is required to pattern the cerebral vasculature, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(2007):16275–16280.

- C. Baron-Menguy, V. Domenga-Denier, L. Ghezali, F. M. Faraci, A. Joutel, Increased Notch3 activity mediates pathological changes in structure of cerebral arteries, Hypertension, 69(2017):60–70.

- T. Xu, S. S. Park, B. D. Giaimo, D. Hall, F. Ferrante, et al. RBPJ/CBF1 interacts with L3MBTL3/MBT1 to promote repression of Notch signaling via histone demethylase KDM1A/LSD1, EMBO J, 36(2017):3232–3249.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- H. Meng, X. Zhang, G. Yu, S. J. Lee, Y. E. Chen, et al. Biochemical characterization and cellular effects of CADASIL mutants of NOTCH3, PLoS One, 7(2012):e44964.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Y. Cao, D. D. Zhang, F. Han, N. Jiang, M. Yao, et al. Phenotypes associated with NOTCH3 cysteine-sparing mutations in patients with clinical suspicion of CADASIL: a systematic review, Int J Mol Sci, 25(2024).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C. X. Dong, C. Malecki, E. Robertson, B. Hambly, R. Jeremy, Molecular mechanisms in genetic aortopathy—signaling pathways and potential interventions, Int J Mol Sci, 24(2023).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A.P. Pan, T. Potter, A. Bako, J. Tannous, S. Seshadri, et al. Lifelong cerebrovascular disease burden among CADASIL patients: Analysis from a global health research network, Front Neurol, 14(2023):1203985.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- J. F. Meschia, B. B. Worrall, F. M. Elahi, O. A. Ross, M. M. Wang, et al. Management of inherited CNS small vessel diseases: the CADASIL example: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association, Stroke, 54(2023):e452–e464.

- W. T. E. Yeung, I. Mizuta, A. Watanabe-Hosomi, A. Yokote, T. Koizumi, et al. RNF213-related susceptibility of Japanese CADASIL patients to intracranial arterial stenosis, J Hum Genet, 63(2018):687–690.

- C. Capone, E. Cognat, L. Ghezali, C. Baron Menguy, D. Aubin, et al. Reducing Timp3 or vitronectin ameliorates disease manifestations in CADASIL mice, Ann Neurol, 79(2016):387–403.

- M. Servito, I. Gill, J. Durbin, N. Ghasemlou, A. F. Popov, et al. Management of coronary artery disease in CADASIL patients: Review of current literature, Medicina (Kaunas), 59(2023):586.

- M. Ihara, K. Washida, T. Yoshimoto, S. Saito. Adrenomedullin: A vasoactive agent for sporadic and hereditary vascular cognitive impairment, Cereb Circ Cogn Behav, 2(2021):100007.

- A. K. Edwards, K. Glithero, P. Grzesik, A. A. Kitajewski, N. C. Munabi, et al. NOTCH3 regulates stem-to-mural cell differentiation in infantile hemangioma, JCI Insight, 2(2017).

- M. Xiu, Y. Wang, B. Li, X. Wang, F. Xiao, et al. The role of Notch3 signaling in cancer stemness and chemoresistance: molecular mechanisms and targeting strategies, Front Mol Biosci, 8(2021):694141.

- C. Giovannini, L. Bolondi, L. Gramantieri, Targeting Notch3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives, Int J Mol Sci, 18(2016).

- J. S. Lee, J. H. Kang, C. H. Kang, J. G. Kim, S. W. Seo, et al. Longitudinal Measurement of Serum Neurofilament Light Chain in Patients With CADASIL, J Stroke, 27(2025):261–265.

- A. S. C. Romero Sr, S. A. T. Holguin Sr, Diagnostic challenge in late onset CADASIL with atypical presentation case report, Alzheimers Dement, 20(2025):e086322.

- A. Madjidov, M. A. Abbott, K. M. Mullen, R. Hicks, G. Schlaug, Case report: Inflammatory CADASIL phenotype associated with a rare cysteine-sparing NOTCH3 variant, Front Hum Neurosci, 19(2025):1568937.

- J. Y. Park, J. Y. Song, J. Y. Chang, D. W. Kang, S. U. Kwon, et al. Genetic and imaging features of CADASIL patients with acute ischemic stroke, Sci Rep, 15(2025):17113.

- Z. Wang, J. Yin, W. Chao, X. Zhang, Inducing mononuclear cells of patients with CADASIL to construct a CSVD disease model, Eur J Med Res, 30(2025) 227.

- X. Men, H. Li, Z. Guo, B. Qin, H. Ruan, et al. Occurrence, risk factors, and prognosis of acute cerebral microinfarcts in CADASIL, Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 12(2025):1171–1178.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- E. R. Lopez-Navarro, S. V. Mayer, B. R. Barreto, K. H. Strobino, A. Spagnolo-Allende, et al. Assessing changes on large cerebral arteries in CADASIL: Preliminary insights from a case-control analysis, J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 34(2025):108294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- F. Hu, W. Xie, M. Fan, Y. Wang, S. Xu, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage in CADASIL, Eur J Neurol, 32(2025):e70100.

- Y. Zhao, Y. Lu, F. Wang, Y. Wang, Y. Li, et al. Mechanistic advances in factors influencing phenotypic variability in CADASIL: A review, Front Neurol, 16(2025):1573052.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- C. Li, H. Li, X. Men, Y. Wang, X. Kang, et al. NOTCH3 mutation causes glymphatic impairment and promotes brain senescence in CADASIL, CNS Neurosci Ther, 31(2025):e70140.

- L. F. Ibañez Valdés, H. Foyaca Sibat, Meningeal lymphatic vessels and glymphatic system in neurocysticercosis. A systematic review and novel hypotheses, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses, 17(2023).

- A. Bugallo-Casal, E. Muiño, S. B. Bravo, P. Hervella, S. Arias-Rivas, et al. NOTCH3 variant position affects the phenotype at the pluripotent stem cell level in CADASIL, Neuromolecular Med, 27(2025):18.

- A. A. Jolly, S. Anyanwu, F. Koohi, R. G. Morris, H. S. Markus, Prevalence of fatigue and associations with depression and cognitive impairment in patients with CADASIL, Neurology, 104(2025):e213335.

- A. Joutel. The pathobiology of cerebrovascular lesions in CADASIL small vessel disease, Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol, 136(2025):e70028.

Copyright: © 2025 Lourdes de Fatima Ibanez Valdes, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.